POSTCARDS FROM OLD LONDON

THE KINGSWAY TRAMWAY TUNNEL

by

DAVE HILL

The Kingsway Tramway Subway is a cut-and-cover Grade II Listed tunnel in Central London,

built by the London County Council (LCC) and the only one of its kind in Britain.

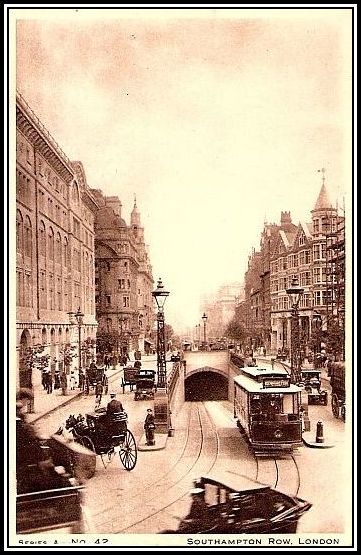

The Kingsway Tramway Subway connected Southampton Row in the north

The Kingsway Tramway Subway connected Southampton Row in the north

with The Embankment in the south and ran under Kingsway and The Aldwych.

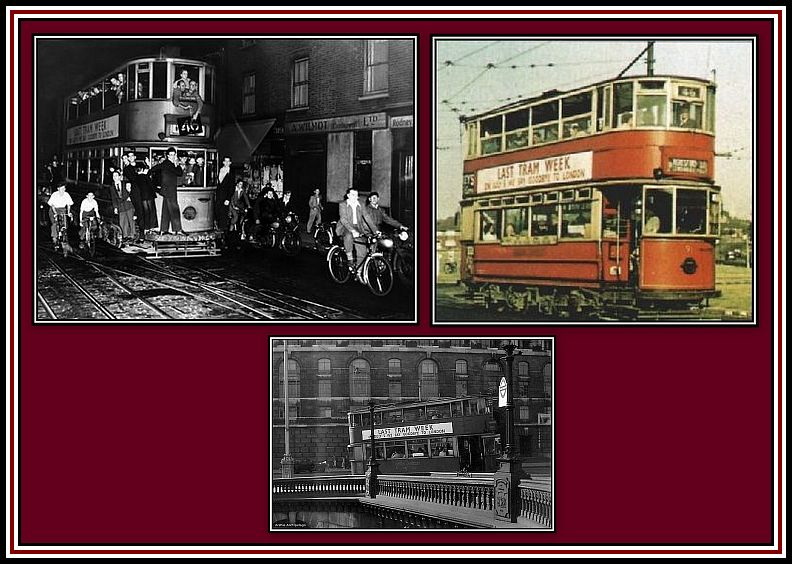

At first, only single decker trams were used to travel through the Subway,

At first, only single decker trams were used to travel through the Subway,

but following changes to the structure during the 1930s, double-deckers trams were able to be used.

The Kingsway Tramway Subway was opened to the public on 24th February, 1906 and continued in service until 5th April, 1952.

——oooOOOooo——

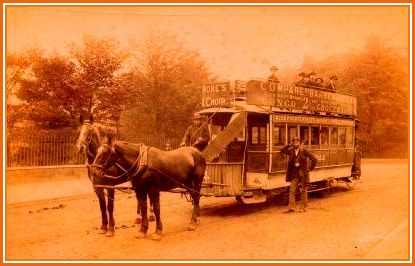

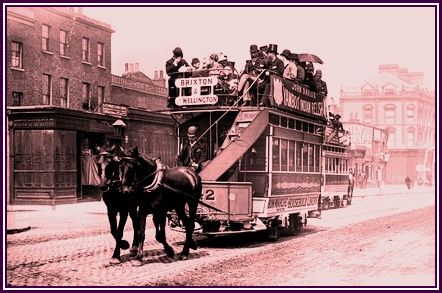

The first tram was introduced into London in 1860 by George Francis Train, an eccentric American. It was a horse drawn vehicle and ran along Victoria Street to Westminster on rails that had been secured to the road surface. Naturally this arrangement impeded other traffic, which soon brought opposition to this mode of transport. Later Parliament permitted the introduction of trams to London, but with the proviso that the rails were built into the roadway. In addition, the tram companies were to bear the maintenance costs including road repairs and were allowed to charge one penny (1d) per mile with half-price fares for early and late travel for workers.

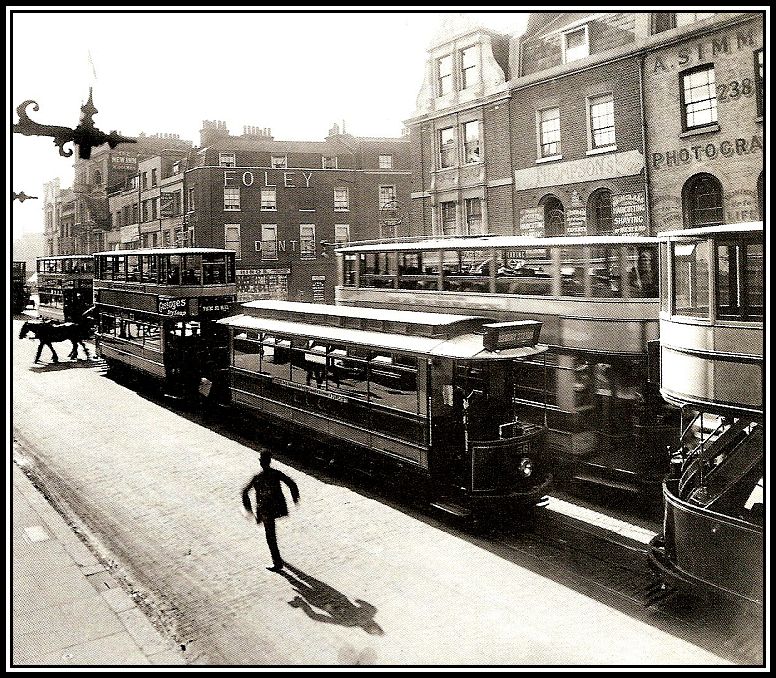

Trams were immediately popular with the public and soon there were commonplace in London. They were cheaper than the other forms of public transport at the time and allowed more passenger-room and gave a smoother ride. The earliest trams carried a maximum of 60 passengers and were pulled by two horses. By 1901, electric trams were introduced and the last horse-drawn tram finally ran in 1915.

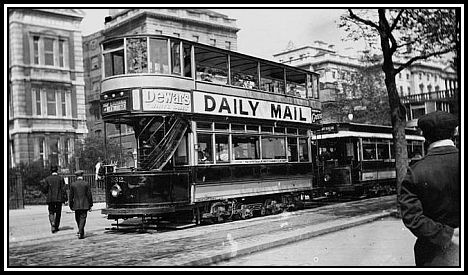

Trams on Westminster Bridge Road, 1912

Trams on Westminster Bridge Road, 1912

Photograph borrowed from Trams

Prior to the introduction of electric trams several other ways of powering a tram were tried out. These included motor-power (1873-1891), compressed air (1881-1883) and cable (1891-1906). There were two cable tram services that once operated in London. In 1891, the first cable line in Europe was introduced into operation on Highgate Hill and the second went into service between Brixton and Streatham. Both were replaced by electric trams by 1906.

The first electric tram was tested on the West Metropolitan Tramways Acton-to-Kew route following the invention of the storage battery in 1883. Despite this, the first fully operational electric tram with power supplied by overhead wires was only introduced by the Croydon Corporation in 1901. At about the same time, Imperial Tramways, after renovation and extension of its routes and being renamed the London Tramways also employed the same type of power supply to its trams.

There were over 300 electric trams operating in London by 1903. London County Council (LCC; the forerunner of the Greater London Council) began operating its first electric line between Westminster Bridge and Tooting in May 1903 with immediate success. The company believed that with tram service, social change would come, as cheap and efficient transport would lead to workers moving to the suburbs and so enjoy a healthier lifestyle. Although the tram services were popular, the City of London and the West End never permitted them to be introduced. The success of the LCC tram service soon led to other London boroughs introducing electric tram services, and by 1914, London had the largest tram network in Europe. However, progress came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of war. Once men entered military service, women stepped in to keep the services running.

Fortunately each of the operating tram companies employed the same standard gauge between the rails, which was to allow possible future linking of services. In 1900, the companies were brought together under the control of LCC.

For a number of years, the LCC had wanted to connect its northern network with those of the south. With such a connection, the company could send trams from all over London for service at its Central Repair Depot at Charlton in South East London. In 1902, plans were proposed to build a subway or tunnel from Theobalds Road in the north to the Embankment where it would surface at Waterloo Bridge and continue across the bridge into South London.

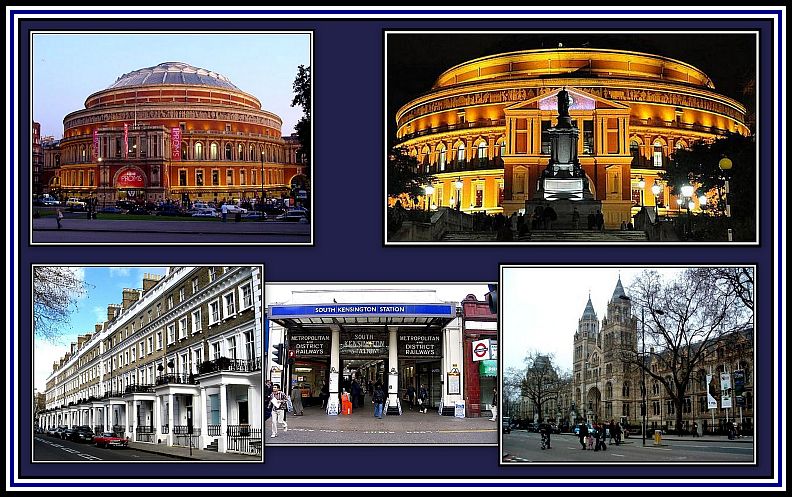

Prior to the proposal to build the Kingsway Tramway Subway, an underground tram line between South Kensington and the Royal Albert Hall had been suggested, but plans were abandoned in 1891 in favour of a pedestrian route. However, the proposal to build the Kingsway Tramway Subway for a tram route was to become reality in 1902.

Upper Row: The Royal Albert Hall, Kensington – site of the Promenade Concerts and other events

Upper Row: The Royal Albert Hall, Kensington – site of the Promenade Concerts and other events

Lower Row: left, row houses; centre, Underground Station; and right, Victoria and Albert Museum

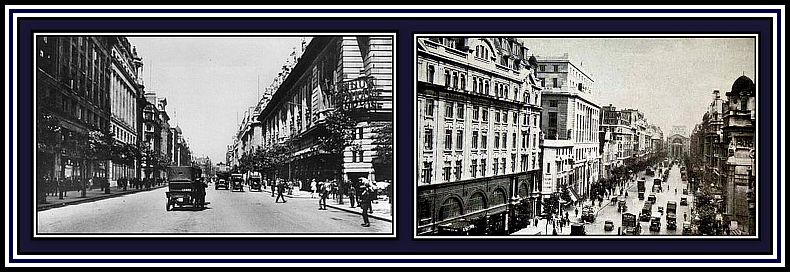

The proposed underground route would allow the LCC to take the advantage of the proposal first made in 1898 to demolish one of London’s last remaining slum rookeries between Holborn and The Strand and to redevelop the area. A new road, to be named The Kingsway after Edward VII, was to be built with the tunnel beneath and would connect Southampton Row in Holborn in the north to the broad newly built semicircular road, the Aldwych, which contained the new Bush House complex, on its south side. Both ends of the Aldwych joined The Strand with eastbound traffic being streamed into the Aldwych while westbound traffic continued along The Strand. The western junction of the Aldwych and The Strand also formed a crossroad serving Waterloo Bridge and which itself crossed the Victoria Embankment and the Thames. The redevelopment of the slum area with a tram route beneath would thereby allow increased access between areas of North and South London.

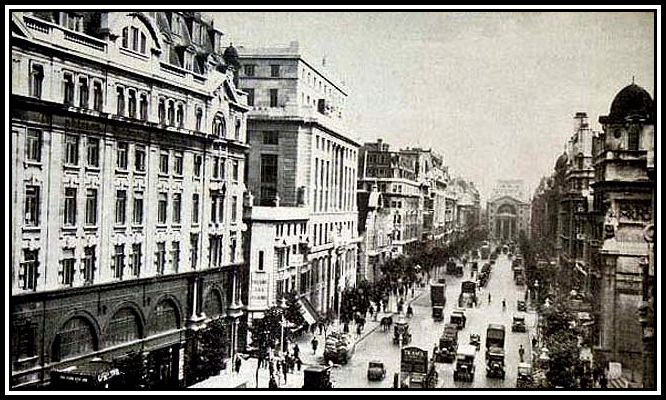

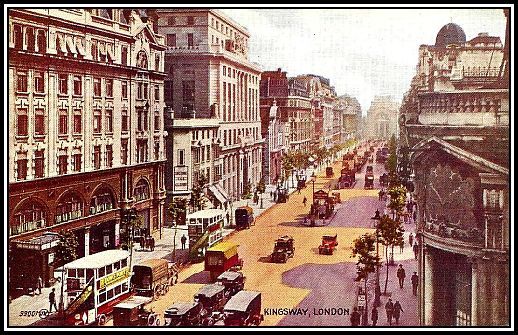

Kingsway in 1920 – looking south from Holborn towards Bush House in The Aldwych

Kingsway in 1920 – looking south from Holborn towards Bush House in The Aldwych

The proposal to build the tunnel beneath Kingsway and on to the Embankment met with both legal and logistic problems and permission was not fully granted until 1906. The Kingsway part of the tunnel was approved in 1902, but permission to continue to the Embankment took another four years to achieve. Parliament advanced a number of reasons for this and perhaps the most ridiculous was that the tram line would interfere with Members crossing the road to reach St. Stephen’s Club! Permission was never granted for trams to cross Waterloo Bridge. In addition, due to the presence of a sewer (carrying the River Fleet) at the northern end and the District Railway at the southern end, the subway would only be able to support passage of single-decker trams.

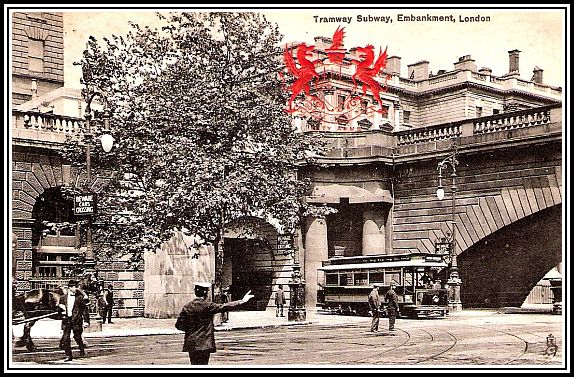

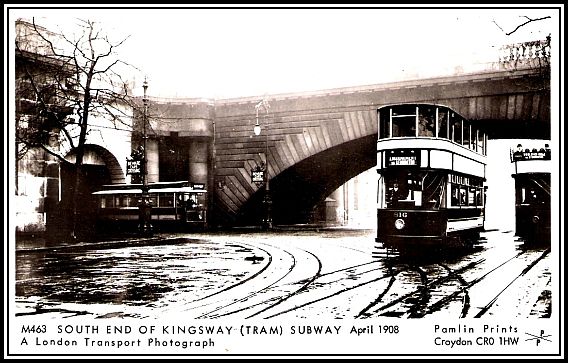

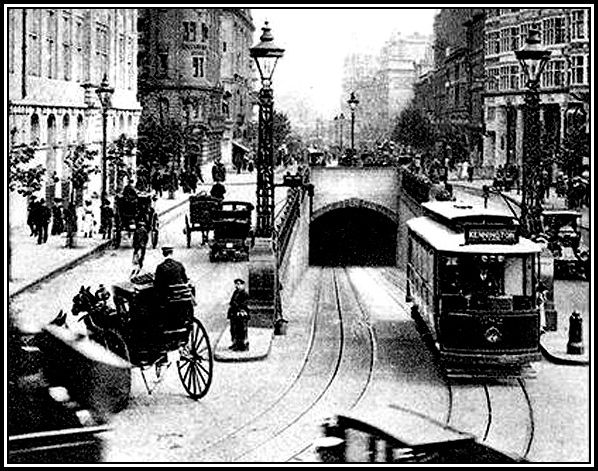

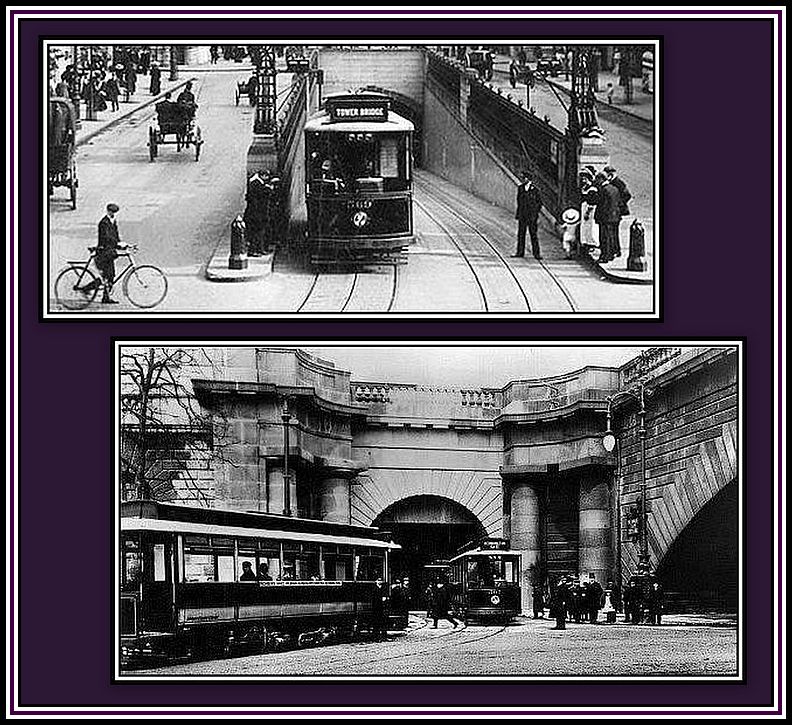

The Kingsway Tramway Tunnel soon after its opening to the public

The Kingsway Tramway Tunnel soon after its opening to the public

However, later in the 1930s, double-decker trams were at last able to go through the tunnel with the removal of the arches and its deepening.

After leaving the tunnel at the Embankment, trams were to turn right and continue on to Westminster Bridge or turn left and cross the Thames via Blackfriars Bridge and travel to the Hop Exchange in Southwark.

Left: Blackfriars Bridge; Right: the Hop Exchange

Left: Blackfriars Bridge; Right: the Hop Exchange

However, overhead wires were not allowed in this section of track and current was taken by a plough from a conduit buried in the road. This system of supplying power to the tram was not without its problems, as the conduit tended to accumulate fallen leaves and other debris and so impede the flow of current. In 1930, service to the Hop Exchange was withdrawn due to poor patronage and the tracks were taken up.

Tram crossing Westminster Bridge – note the absence of overhead wires

Tram crossing Westminster Bridge – note the absence of overhead wires

and the addition of a central groove (Conduit) in the road where the source of current was hidden from the public.

The Conduit at the Holborn Entrance today

The Conduit at the Holborn Entrance today

In 1937, the rebuilding of Waterloo Bridge necessitated movement of the southern entrance/exit to the tunnel. This required its repositioning to a new position centrally underneath the bridge. The newly built entrance/exit was opened for service on 21st November, 1937.

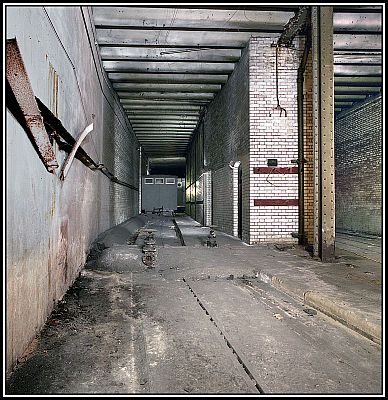

Kingsway Tramway Tunnel undergoing changes to allow passage to double-decker trams.

Kingsway Tramway Tunnel undergoing changes to allow passage to double-decker trams.

Photograph provided by Leonard Bentley.

The tunnel was to have intermediate stations along Kingsway, which could be accessed by stairs. Stations were built at Holborn and Aldwych, but others although proposed were never built.

The Kingsway Tramway Subway opened to public access on 24th February, 1906 with a service between The Angel and The Aldwych. In November, the route was extended to Highbury Station, and in April 1908, routes were extended to Tower Bridge, Kennington and the Elephant & Castle.

Some drivers experienced major difficulties managing the northern approach of the tunnel at Southampton Row. The approach was 170 feet in length with a 1:10 gradient and this could prove problematic to manipulate by inexperienced drivers and trams were occasional seen rolling backwards. Later, only operators with at least two years duty on other services were allowed to work on routes traveling through the tunnel.

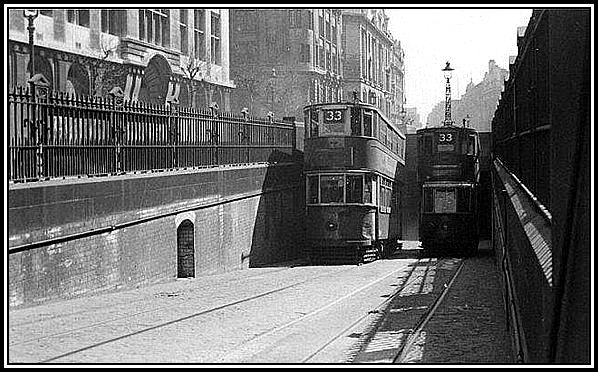

In 1933, the LCC tram service was taken over by the London Passenger Transport Board. The newly formed organisation quickly made the decision that all London trams should be replaced with more modern vehicles. Trams began to be replaced in 1935 and were mostly replaced with trolleybuses. By 1940, only trams in South London and on those routes traveling through the Kingsway Tunnel, routes 31, 33 and 35, were still in operation.

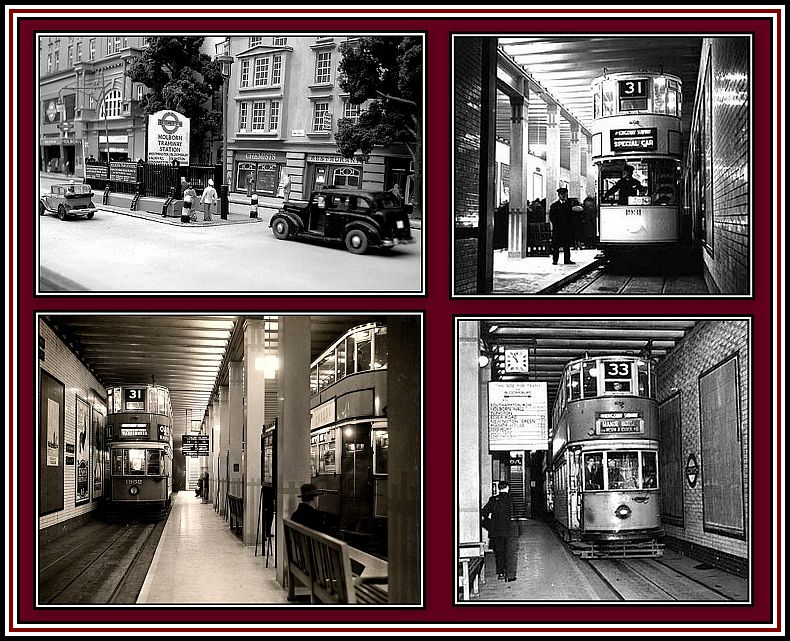

Left: Tram Route 33 at Aldwych Station; Right: Tram Route 31 at Holborn Station

The first route using the tunnel to be withdrawn was route 31 on 1st October, 1950. However the tunnel remained in operation until 1952 with the last tram in regular service passed through it on Saturday, 5th April. However there were two specials soon after midnight for members of the public wishing to say their goodbyes. During the early hours of the next morning, the remaining trams still in North London passed through the tunnel and were driven to depots in South London.

At the height of its popularity, London’s network of trams covered much of the inner city and reached into the suburbs. Assisted by the Kingsway Tunnel, the longest tram route in London was able to operate some 16 miles. This was a weekend service that ran between Archway and Downham passing through Brockley.

The Archway

Top: Archway Bridge also known as Suicide Bridge, as it is a favourite venue for such occurrences

Bottom: left, view from the bridge; centre, Samaritans information on the bridge; and right, bus sign

It was at the Archway that Dick Whittington heard the sound of Bow Bells

urging him to turn again and return to London where he was to become Lord Mayor.

The last tram ran in London on 5th July, 1952 and the tracks were quickly removed

except for those in the Kingsway Tunnel.

The tunnel was now without a use, but in 1953, the London Transport Executive used it to store 120 buses and coaches for possible use during The Coronation. Various proposals were next put forward for future use of the tunnel. These included converting it into a car park, a film studio and a storage facility. The area was leased to a storage company in October 1957 for a while.

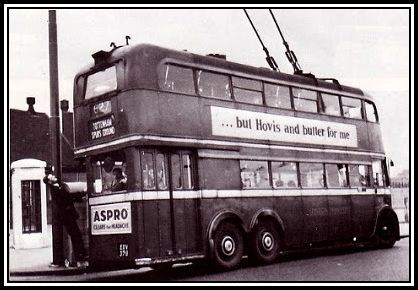

It seems likely that there was once a plan that trolleybuses should pass through the tunnel. Trolleybus number 1379 was built especially for testing. Testing proved unsuccessful since trolleybuses would need to run on battery power when traveling through the tunnel, as headroom restriction precluded the use of overhead wires carrying current. This bus had exits with folding door on both sides and went into normal service on other routes once the plan was abandoned.

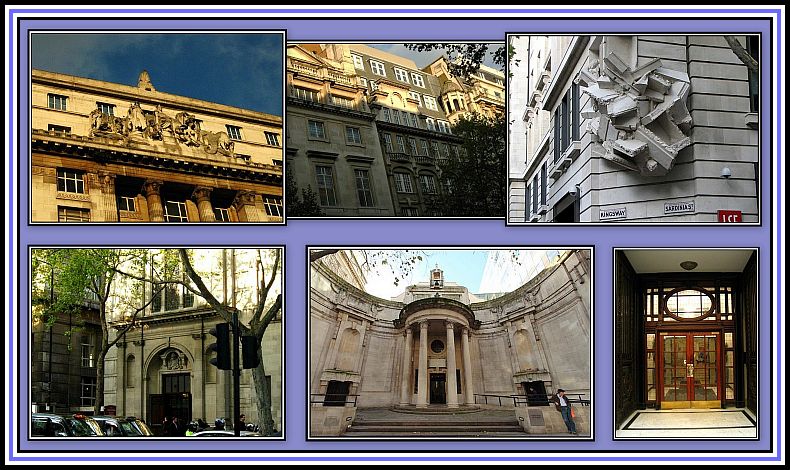

The LCC proposed using part of the tunnel for light traffic in June 1958. In the hope of reducing traffic congestion from Waterloo Bridge at The Strand, it was suggested that the southern region of the tunnel be used as an Underpass. Permission was granted in April 1962 and construction began on the conversion in September and the Strand Underpass was opened to traffic on 21st January, 1964.

The Strand Underpass

The Strand Underpass

Right: Entrance at The Strand; Left: Exit at Kingsway, close to where the Stoll Theatre once stood

The remaining southern section of the tunnel between the Embankment and The Strand was subsequently abandoned and the entrance/exit under Waterloo Bridge was closed by heavy metal doors. The doors remained in place until 2007 when a branch of the Buddha Bar chain of bar/restaurants opened. Conversion of the area into a bar/restaurant required extensive work involving the demolition of the pedestrian subways under the bridge and extensive reconstruction of the area under the bridge.

Kingsway Tramway Subway under Waterloo Bridge.

Kingsway Tramway Subway under Waterloo Bridge.

This area was converted into a Buddha Bar Restaurant.

In early 2013, I have heard that it is now up for sale.

At present, the northern entrance/exit of the ex-Kingsway Tramway Subway is still there, but remains locked and bolted. The 1:10 gradient is still impressive with the roadway complete with tracks and conduit plunges down to the metal grill and then into the dark under Kingsway.

Top: the northern entrance/exit of the ex-Kingsway Tramway Subway;

Top: the northern entrance/exit of the ex-Kingsway Tramway Subway;

Bottom: the region of the Tunnel to the Aldwych station

The region down to the old Aldwych station is currently abandoned although parts of it have been used from time to time including the housing of a portable building to serve as the Headquarters of Flood Control for the Greater London Council until the opening of the Thames Barrier in 1984.

The Portable Headquarters of Flood Control of the Greater London Council

The Portable Headquarters of Flood Control of the Greater London Council

housed in the tunnel prior to the construction of the Thames Barrier.

Photograph reproduced with permission of Nick Catford

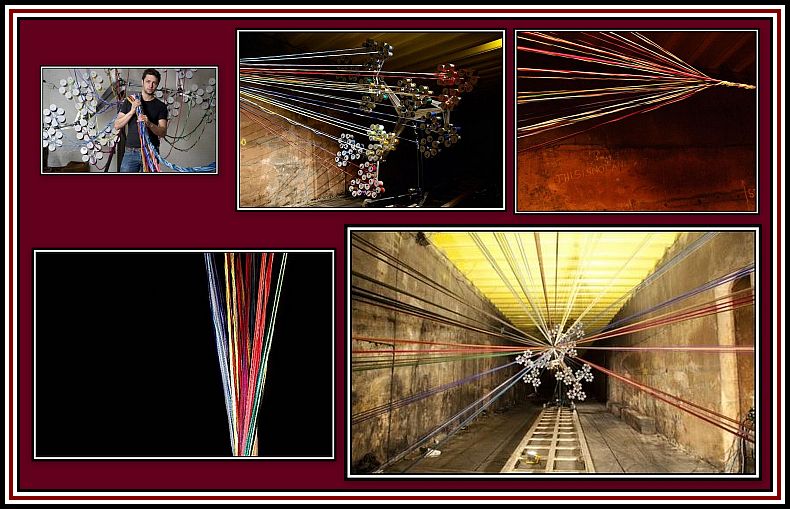

It has also been a storage area of old road signs belonging to the Camden Borough Council; as a site-specific art installation called Chord by Conrad Shawcross between October and November 2009; and as a possible part of the Cross River Tram Project, which would have seen trams once again in Central London and linking north and south areas. Sadly the project was canceled in 2008.

Part of Chord by Conrad Shawcross (Upper left)

Part of Chord by Conrad Shawcross (Upper left)

Recently Camden Borough Council leased the northern section of the tunnel to BAM/Ferrovial/Kier (BFK), the company contracted to build the tunnels for Crossrail. Crossrail is a proposed railway system of 73 miles (118 kilometres) currently under construction in South East England that will link the counties of Berkshire and Buckinghamshire with London and on to the county of Essex. The rail system requires 31 miles (50 kilometres) of new tunnels. A new railway tunnel is being constructed under the Kingsway Tunnel, which requires consolidation of the ground beneath it, hence the necessity to lease the northern section of the tunnel where a shaft has been sunk and grout introduced. Apparently once the new Crossrail tunnel has been constructed, the contractors have said that they will return the Kingsway Tunnel to its present condition.

Crossrail employees at work building a tunnel under The Tunnel

Crossrail employees at work building a tunnel under The Tunnel

One hopes that something will be done with this section of the tunnel in the future. I would think that it would make an excellent adjunct to the Transport for London Museum. I cannot believe that they are displaying everything they have at their Covent Garden and Acton venues.

——oooOOOooo——

MEMORIES OF THE KINGSWAY TRAMWAY TUNNEL

by

Charles S.P. Jenkins

Kingsway in the 1920s

I have always liked Kingsway. It was an impressive road and once the widest in London. The first time I actually remember going there was when I was taken at a very young age to the Stoll Theatre to see Oklahoma! The Stoll was a magnificent theatre that graced this once elegant thoroughfare. Kingsway had been built in the early 1900s as part of a major redevelopment of the area in order to clear the slums present between High Holborn and The Strand. It is hard to believe now that slums once covered this area of London.

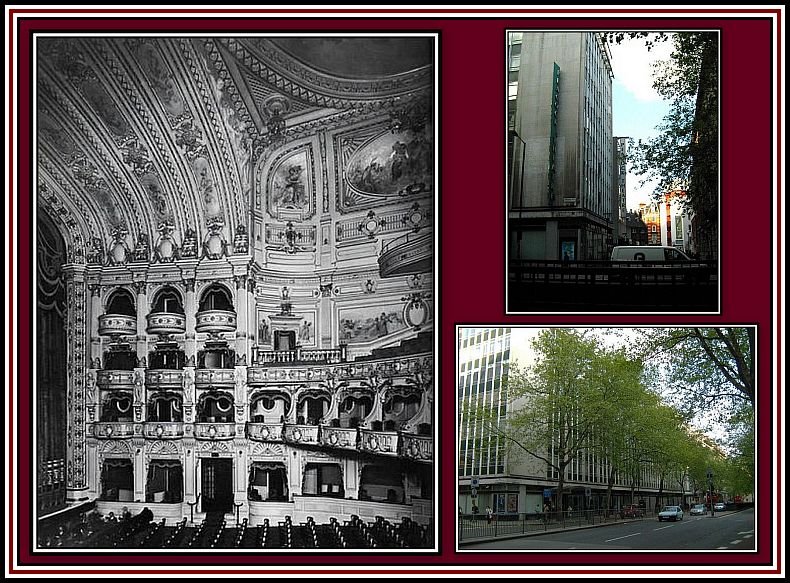

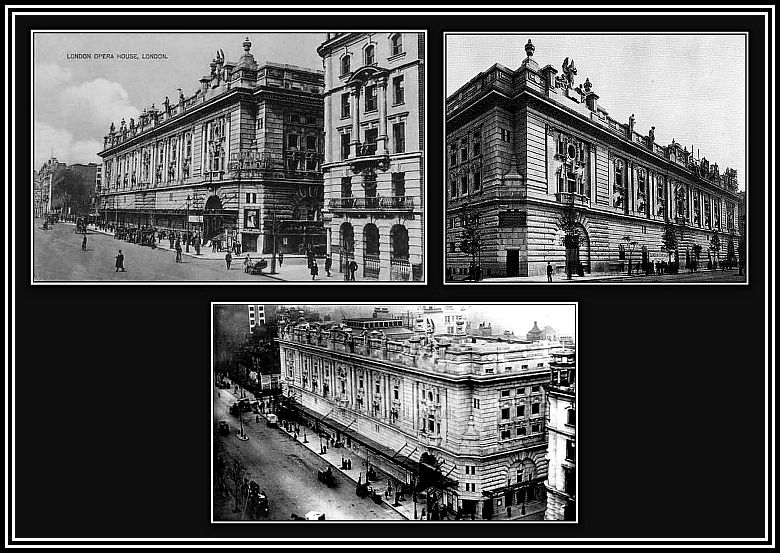

The London Opera House opened on Kingsway on 13th November, 1911. It was built by Bertie Crewe in Beaux-Arts style for Oscar Hammerstein I and was purchased by Sir Oswald Stoll in 1916 who changed its name to The Stoll Theatre.

The theatre suffered from being out of the mainstream of theatres, but did present a number of

successful productions before its closure on 4th August, 1957 and subsequent demolition.

The theatre was replaced by an office block with a smaller theatre in its basement.

Productions and artists of The Stoll Theatre

Productions and artists of The Stoll Theatre

Top Row: posters for Oklahoma! Oklahoma! transferred here from the Theatre Royal Drury Lane with Howard Keel (top right) in the cast

Bottom Row: Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin, founders of The Festival Ballet, presented Where the Rainbow ends at the Theatre

Other presentations included Kismet (the longest running show here), Wild Violets and Porgy & Bess

In addition to The Stoll, the road was once the site of the Kingsway Hall, a Methodist Chapel that also served as a concert hall and recording venue. Both of these glorious buildings have since been demolished and replaced by an office building with a small theatre-cum-cinema-cum-lecture hall in the case of the Stoll and a hotel in the case of Kingsway Hall.

Left: auditorium of The Stoll Theatre (reproduced with permission from Ken Roe)

Left: auditorium of The Stoll Theatre (reproduced with permission from Ken Roe)

Right top: The Peacock Theatre; Right lower: office building that replaced The Stoll

Unfortunately, I do not have any photographs of Kingsway Hall. Those that do exist are apparently subject to copyright restriction. The Kingsway Hall was built in 1912 and was the West London Mission of the Methodist Church. From 1936 until his retirement in 1978, Donald Soper was its superintendent. Dr. Soper’s father was a Methodist, a Liberal and an active member of the Temperance Society and his mother was a supporter of the Women’s Social & Political Union, who were the first group to be known as suffragettes. As a result, he grew up in a home where his parents held strict views against alcohol, gambling and blood sports, which he held throughout his life. After seeing so much poverty in Britain, he became a socialist and he began fiercely preaching against capitalism, the arms trade, blood sports, child labour and the inadequate state help for the poor. Dr. Soper was a remarkable orator and during his tenure at Kingsway Hall, over 400 attending service each Sunday morning and over 1,000 during the evening. These numbers continued up to the early 1960s. He was a pacifist and in 1937 joined the Peace Pledge Union. This led to his being banned from the BBC during the war years since he was considered too persuasive a preacher to be allowed on the radio. Dr. Soper retired in 1978 and the West London Mission moved to the church on Hindle Street in Marylebone with a branch in Kings Cross where a large Chinese contingent is among the congregation. Although officially retired, Dr. Soper continued his criticism of society including the Royal Family for their love of horse racing. He died on 22nd December, 1998.

Top middle: Dr. Donald Soper; Top left: West London Mission, Hindle Street, Marylebone

Top middle: Dr. Donald Soper; Top left: West London Mission, Hindle Street, Marylebone

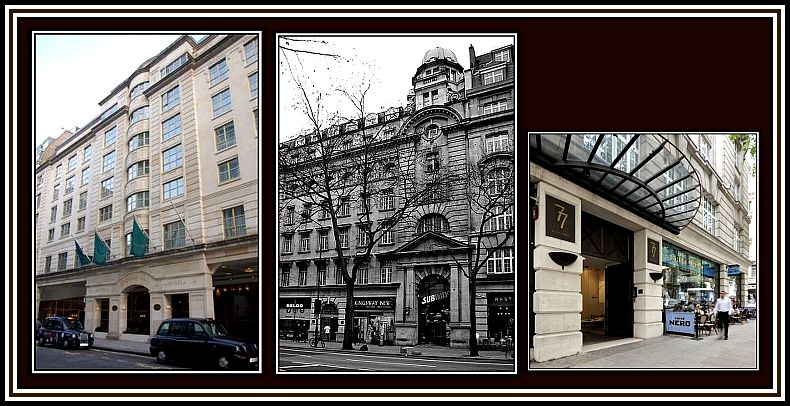

In March 1983, the Greater London Council bought Kingsway Hall. However, the building was in a poor state at this time, and since nothing significant about it could be found about it at this time, it was demolished in 1998 and the Kingsway Hall Hotel was built on the site.

The site of the Kingsway Hall today

The site of the Kingsway Hall today

Left: Kingsway Hall Hotel; Middle: Subway, also on the site of the Hall (at 75 Kingsway); Left: 77 Kingsway

Like so much else today, what is left of Kingsway is but a mere shadow of its former self. However, if you had asked father what it was about Kingsway that appealed to him, his answer, without hesitation, would have been the Kingsway Tramway Tunnel.

Kingsway Tramway Subway in 2011

Kingsway Tramway Subway in 2011

Silician Avenue

Another great wonder of the area close to the Tramway entrance on Southampton Row is Sicilian Avenue

This small walkway was built in 1905 and designed by Worleys and Armstrong.

It was originally named Vernon Arcade, but changed to Sicilian Avenue in 1909,

as a result of the Sicilian limestone used in its construction.

(Information provided by Camden Coucil, Local History)

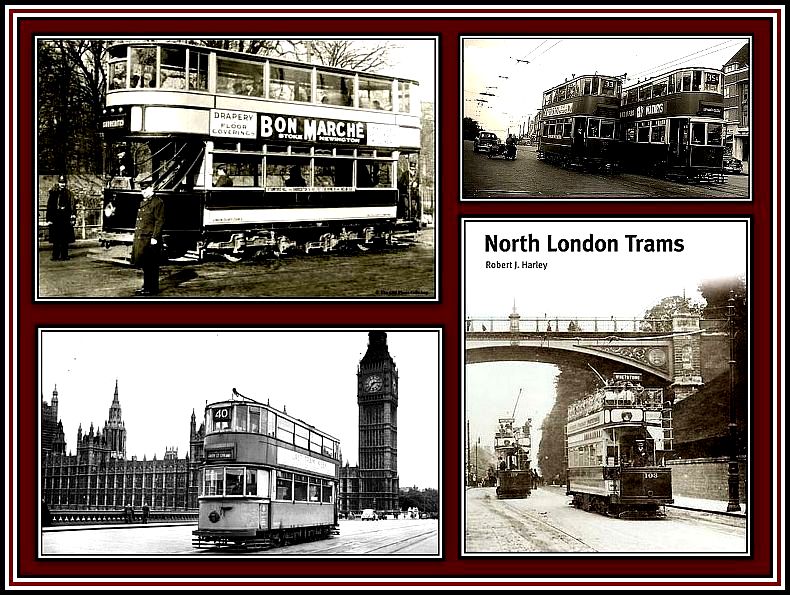

I have found that people who knew the old London trams either loved them or loathed them. I was still very young when trams came to the end of their time on London streets and so memory of them is somewhat clouded and limited. While I was not especially fond of them, father found it a delight to ride on them. He loved to take us to the Elephant & Castle in South London by tram and show us where he had grown up. I found the tram and the journey on it to be somewhat frightening. Firstly, I found trams to be huge hulking vehicles and to be remarkably noisy; secondly, they shook and clattered as they moved along their tracks; and thirdly, the lighting was forever going off as they rumbled and clattered along. However, what I disliked the most was when we stood at the Elephant and watched these great beasts lumber and splutter over the points. As its pole passed over the points at the junction of overhead wires, sparks would flash and fly and I always believed that the tram was about to explode in flames. father dismissed my fears and saw these flashes in the same way others saw a fireworks display.

Bottom right: Cover of the book North London Trams by Dr. Robert J. Harley showing a tram at Archway.

These journeys to the Elephant meant a ride through the Kingsway Tunnel. As I said, I was very young at the time of these outings and did not quite understand why we were being thrown down that enormous gradient at the northern end of the tunnel and then being plunged into darkness for the lighting of the tram always seemed to go out as we did. Of course, I cannot totally trust my memory here, but even if the lights went out only once, the event was sufficiently traumatic to me that I now remember every journey beginning in this way!

Boarding the tram at the Holborn Tramway Station to the Elephant

I have a memory of travelling through the tunnel on a trolleybus and, for years, I swore to the truth of this. However, I fear that this memory is based on a dream rather than in reality. There was one trolleybus, number 1379, which was especially built for feasibility testing to see if trolleybuses could be used in the tunnel. This trolleybus was built and tested sometime before I was born and so it would appear that my remembrance is more ethereal than substantial.

Trollybus Number 1379

From the feasibility studies, it was concluded that trolleybuses could not function efficiently in the tunnel. Apparently there was not enough space for the bus to proceed with ease along its length and not enough height to allow overhead live wires. One would have thought that had someone and a colleague with a tape measure had gone into the tunnel and taken a few simple measurements, the company could have saved on the cost of building a special trolleybus to learn the same! After testing, the right folding rear door of the special trolleybus was sealed shut and then entered regular service. As a child I remember seeing it often and even riding on it a few times when it was in service on route 653, Aldgate to Tottenham Court Road. I remember the folding door at the rear and the position of the stairs to the upper deck being a few steps into the lower deck and not at the rear as with other buses.

I remember my father discovering that the tunnel was to close. He read the report aloud from one of the evening newspapers. At that time, London had three evening newspaper, The Star, The Evening News and The Evening Standard, which cost one old penny each. I can remember my father’s reaction. He was not pleased, while my mother and I just said and listened. The full impact of the closure was totally lost on me, I fear, but not on my father. He complained bitterly and was very annoyed. Eventually my mother stepped in, but her comments only made things worse and he went into one of his sulks. When he went into such a mood, his only solace came from going down to the shop (my parents managed a pie ‘n’ mash shop at the time) and talk to his dog!

Fortunately my father was an animal person and I never knew a dog that did not warm to him. Our dog of the moment was especially good at consoling my father. We lived on a very dangerous major artery out of London with constant heavy traffic. Despite all efforts, our dogs insisted on waiting at the entrance to the shop for my father whenever he went out. Each one enjoyed racing towards him when they sensed his return. Sadly, their enthusiasm to rejoin my father often proved dangerous and led to their untimely deaths, as they raced into the road oblivious of the on-coming traffic. I cannot begin to recount the trauma that this caused my family and me. I feel as if I spent most of my childhood in mourning! Anyway, despite the sadness, on the following Sunday morning my father was off to Club Row Market to find another companion.

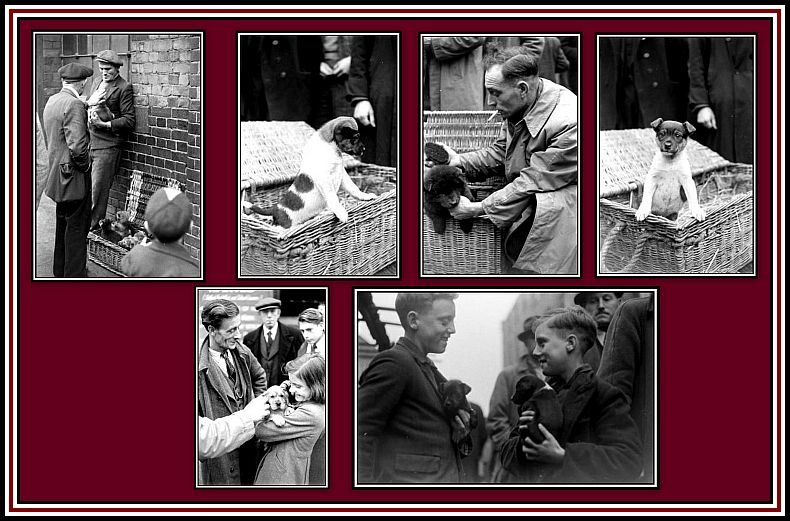

Club Row Dogs

A puppy could be had for Five Shillings (25 new pence) – most dogs were mongrels despite what

British Pathe says in its film!

The R.S.P.C.A. eventually had the market closed down in 1983 – a sad day for all dog lovers.

Once my father returned from being comforted by our dog, he announced that we had to go for one more ride through the tunnel. I am sure that my mother’s heart sunk, as did mine, but who were we to deny him this one last joy? And so we went. I have no recall of this final voyage, but I am sure that the tram spluttered and clanged its way through the tunnel and I breathed a sigh of relief once we came out onto the Embankment.

——oooOOOooo——

Time has the ability to cause us to rethink our past viewpoints. Naturally, my opinion of the Kingsway Tram Tunnel has been revised and I now consider myself lucky to have traveled through it. I like to think that I was too young to appreciate the journey and, at times, I can even make myself believe that it wasn’t so bad and that I exaggerated my dislike simply to make the trip sound amusing to those listening to me. However, if truth be told, the journey through the tunnel was totally wasted on me and I regret not being of an age to share its joys with my father.

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to RETURN to the POSTCARDS FROM OLD LONDON Home Page

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to RETURN to the TABLE OF CONTENTS

——oooOOOooo——

Dear Dave Hill,

Love your stories of London website. Wonderful stuff, keep history alive. I was searching for a picture of Southampton Row in the early 1900’s and had no idea about the trams there. Thank you.

Genny Haines

I was a teenage school boy (living in Pinner) and used to regularly ride the trams at half term and holidays with a friend who I believe went on to a career with London Transport at one of the Tube works.

I rode through the Kingsway subway the day it shut and I was also in Beresford Square, Woolwich when the last tram of all went through. (I nearly had to walk all the way home to Pinner but my Dad came to find me in the car!).

Happy memories and very vivid still.

I went through with my parents from the Embankment northwards aged about 4.

I was terrified of fire then and as the darkness of the tunnel began I screamed blue murder saying we are going to be burnt!

Not until my mother pointed at the street sign THEOBALD’S ROAD.

I thought we were in heaven!

About 9 years later I walked the whole tunnel with another bus spotting friend. We got shouted at but we were allowed to continue to the inclined opening in Kingsway. An unforgettable experience.

Thank you very much for sharing your terrific story with us. I appreciate it very much. Charles

Like you remembered the trolleybuses I’m sure I remember as a small boy when I went to Exhibition of 1951 sitting on as scaffold erected on the north bank watching trams exiting the south end of theHolborn tunnel on Waterloo bridge but I see reference to the southern end of the tunnel being converted to vehicle traffic. I can’t however find reference to when this southern end was built and whether trams ever did exit on Waterloo bridge. Can you help please

Rarely opened to the public since it closed in 1952, London Transport Museum will be conducting tours of the Kingsway tram subway in for a couple of months this summer.

It would be awesome if they opened it up more frequently. It’s something I’d love to do but probably won’t get the opportunity to visit this year.

Imagine how brilliant it would be if they parked heritage tram there, giving people a real feeling of what it was like back in the day. There’s so much they could add to make it something of a museum – that would certainly bring in some money and sell it as an add-on to a London Transport Museum ticket.

Thank you for your comment.

If I were in charge of the London Transport Museum, I would put your suggestion into motion. It would be wonderful to go through the Tunnel (even just a part) on a Tram again.

Thanks again for writing.

I remember going on the trams in the tunnel and coming out on the Emankment in about 1944.Thanks for the pictures.