A SERIES OF WALKS ALONG THE EMBANKMENT

THIS PAGE IS PRODUCED IN CONJUNCTION WITH

DAVE HILL

PART TWO: FROM NEW SCOTLAND YARD TO

THE SHELL MEX HOUSE

New Scotland Yard – Past & Future

Our walks along The Embankment on sunny afternoons or during early evenings would be constantly interrupted once we came to a site of special significance to my father. When this happened, and it happened often, we had to pause and renew our acquaintance with the site. Unfortunately for me, my father could not and would not be rushed at such times! My mother solved any ennui that she might have experienced by finding the nearest public bench where she was happy to wait.

The benches along The Embankment are of cast iron and were installed in 1874. They were designed by Lewis & G. F. Vulliamy and cast by Z.D. Berry & Son and have been Grade II listed by English Heritage. It is interesting to note that there are two varieties of benches on The Embankment: Sphinx Benches in the City of Westminister and Camel Benches in the City of London.

Seating and Lighting Along The Embankment – Sphinx Benches

Seating and Lighting Along The Embankment – Sphinx Benches

Seating and Lighting Along The Embankment – Camel Benches

Seating and Lighting Along The Embankment – Camel Benches

Street Lamps Along The Embankment

Street Lamps Along The Embankment

-oOo-

New Scotland Yard, Cleopatra’s Needle, and Shell Mex House were sites that my father enjoyed gazing at for long periods of time.

-oOo-

NEW SCOTLAND YARD

The Metropolitan Police (The Met) had its original headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place. The building had a rear entrance on Great Scotland Yard, which was used by the public. Over time, Scotland Yard has become a metonym for The Met’s headquarters no matter where it is actually located.

In 1874, a Black Museum, The Crime Museum of Scotland Yard, unofficially came into being, as a collection of criminal memorabilia. It became an official museum in 1875, but was not open to the public. Its purpose is to serve as an aid to the police in their study of criminals and criminal activity.

In 1890, The Met moved to its most famous location, New Scotland Yard on The Embankment, which served as its headquarters until 1967 with the Black Museum being housed in the basement. The buildings were designed by the architect, Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912) and built between 1887-1906 with granite quarried by convicts on Dartmoor. The buildings are recognisable throughout the world through films and television series and are Grade 1 Listed by English Heritage. Since 1979, they have been used as Parlimentary Offices and are known officially as the Norman Shaw Buildings.

Postcard of The Victoria Embankment & New Scotland Yard provided by Mr. Dave Hill

Postcard of The Victoria Embankment & New Scotland Yard provided by Mr. Dave Hill

In 1967, The Met moved its operation Headquarters to 10 Broadway in Victoria with the building taking the name, New Scotland Yard. The Black Museum was moved here in the 1980s and has since been renamed The Crime Museum and housed in Room 101.

The Revolving Sign before New Scotland Yard at 10 Broadway

The Revolving Sign before New Scotland Yard at 10 Broadway

In 2013, it was announced that The Met’s Headquarters were to move from 10 Broadway to the Curtis Green Building (Whitehall Police Station) on The Embankment, which is adjacent to the Norman Shaw Buildings. The Building was designed by William Curtis Green (1875-1960) and built between 1935 and 1940. It has always been associated with Police activities and has served as the Headquarters of The Met during the Second World War. The Building is to be redesigned and refurbished and will be renamed, Scotland Yard at the time of opening. Apparently the revolving sign and The Crime Museum are also to move here.

-oOo-

-oOo-

Occasionally, my father would allow himself to speak, for he was not one to waste words, and he allowed his thoughts to be translated into speech and relate tales where he speculated on the identity of Jack the Ripper or discussed other villains such as Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen (1862-1910) who was accused of murdering his wife.

Dr. Crippen fled to Canada together with his mistress, Miss Ethel Le Neve (1883-1967), but were caught upon arrival and brought back to the U.K. where he was tried, convicted and hanged in 1910. He holds the distinction of being the first criminal to be captured through the use of Wireless Telegraphy.

Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen seen (Top Left) in the dock with Miss Ethel Le Neve; Miss Le Neve was tried for accessory in the murder of Dr. Crippen’s wife, Corrine (Cora) Turner in August 1910

Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen seen (Top Left) in the dock with Miss Ethel Le Neve; Miss Le Neve was tried for accessory in the murder of Dr. Crippen’s wife, Corrine (Cora) Turner in August 1910

-oOo-

CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLE

Cleopatra’s Needle was erected on the Victoria Embankment in August 1878 after a long and treacherous journey from Egypt to England. The obelisk was a gift to Britain by Muhammad Ali Pasha (1769-1849), a Turkish–Albanian commander in the army of the Ottoman Empire, who was Wāli (Governor) and self-declared Khedive (Viceroy, the representative of a monach) of Egypt and Sudan. The gift was presented in 1819 in recognition of the victory by the British fleet, under the direction of Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson (later Lord Nelson) over that of Napoleon during The Battle of the Nile in 1798.

The Destruction of L’Orient at The Battle of the Nile by George Arnald (1762-1841)

The Destruction of L’Orient at The Battle of the Nile by George Arnald (1762-1841)

Left: Lord Nelson by Lemuel Francis Abbott (1760-1802); Right: Muhammad Ali Pasha by Auguste Couder (1790-1873)

-oOo-

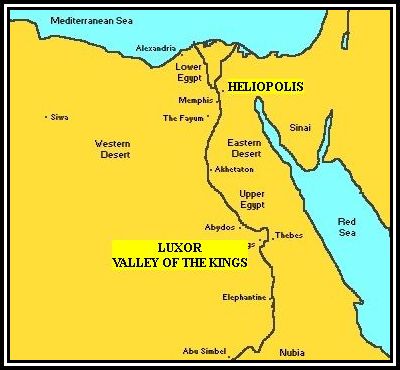

There are three obelisks known as Cleopatra’s Needle that were brought from Egypt as gifts to Britain, the United States and France. The obelisk now re-erected in Paris has its twin still present at the entrance of The Temple of Luxor while those re-erected in London and New York are a pair originally installed in the City of Heliopolis.

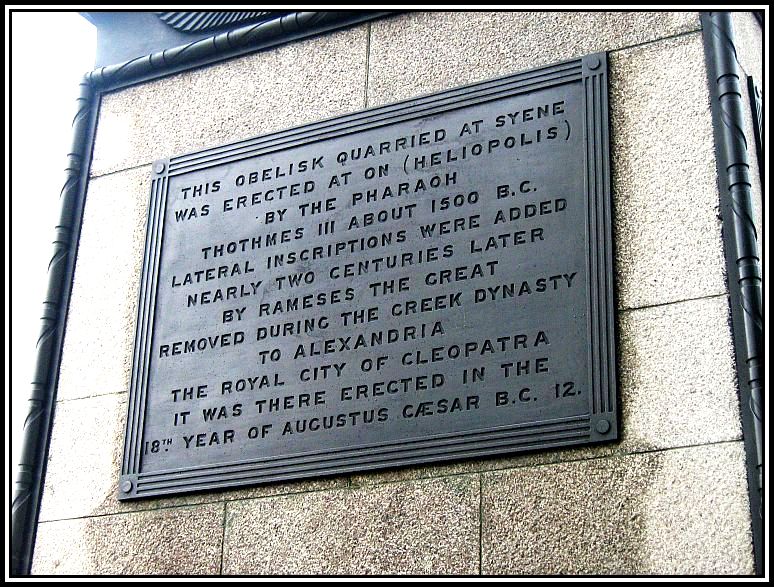

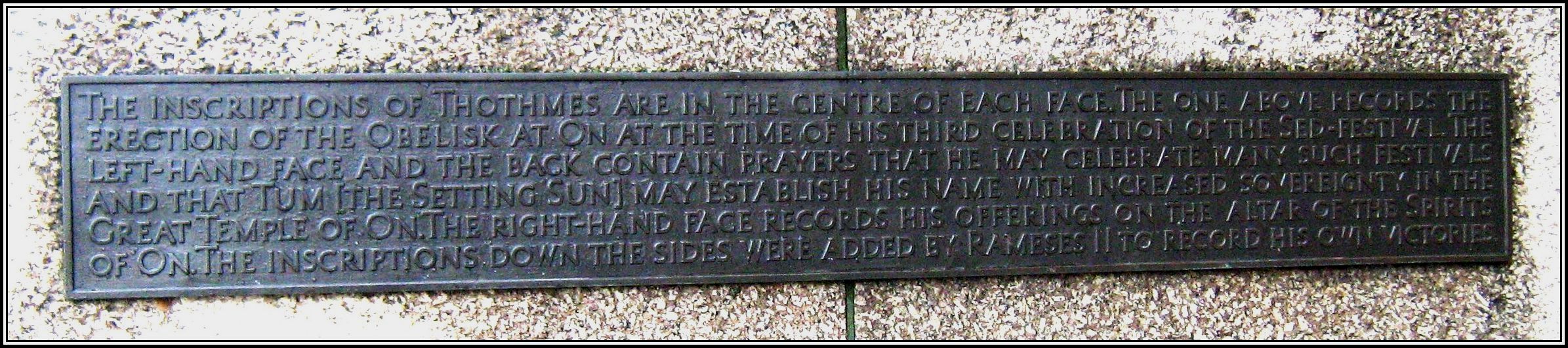

Although the name, Cleopatra’s Neddle, is most generally associated with the obelisk now present in London, none is actually associated with Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt (69-30 BC), since they were made over a thousand years prior to her reign. Both the London and New York obelisks are of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Thutmose III (c. 1543–1292 BC) while the one now present in the Place de la Concorde in Paris is from the reign of 19th Dynasty Ramesses II (c.1303-1213 BC).

The Luxor Obelisk (L’Aiguille de Cleopatra) re-erected in 1833 in the Place de la Concorde

The Luxor Obelisk (L’Aiguille de Cleopatra) re-erected in 1833 in the Place de la Concorde

The Romans moved the future London and New York obelisks to Alexandria in 12 BC and re-erected them in a temple originally built by Cleopatra in honour of either Mark Antony or Julius Caesar. At some time afterwards, the obelisks were toppled and their faces became buried, which help preserve most of the Hieroglyphs from the effects of weathering.

-oOo-

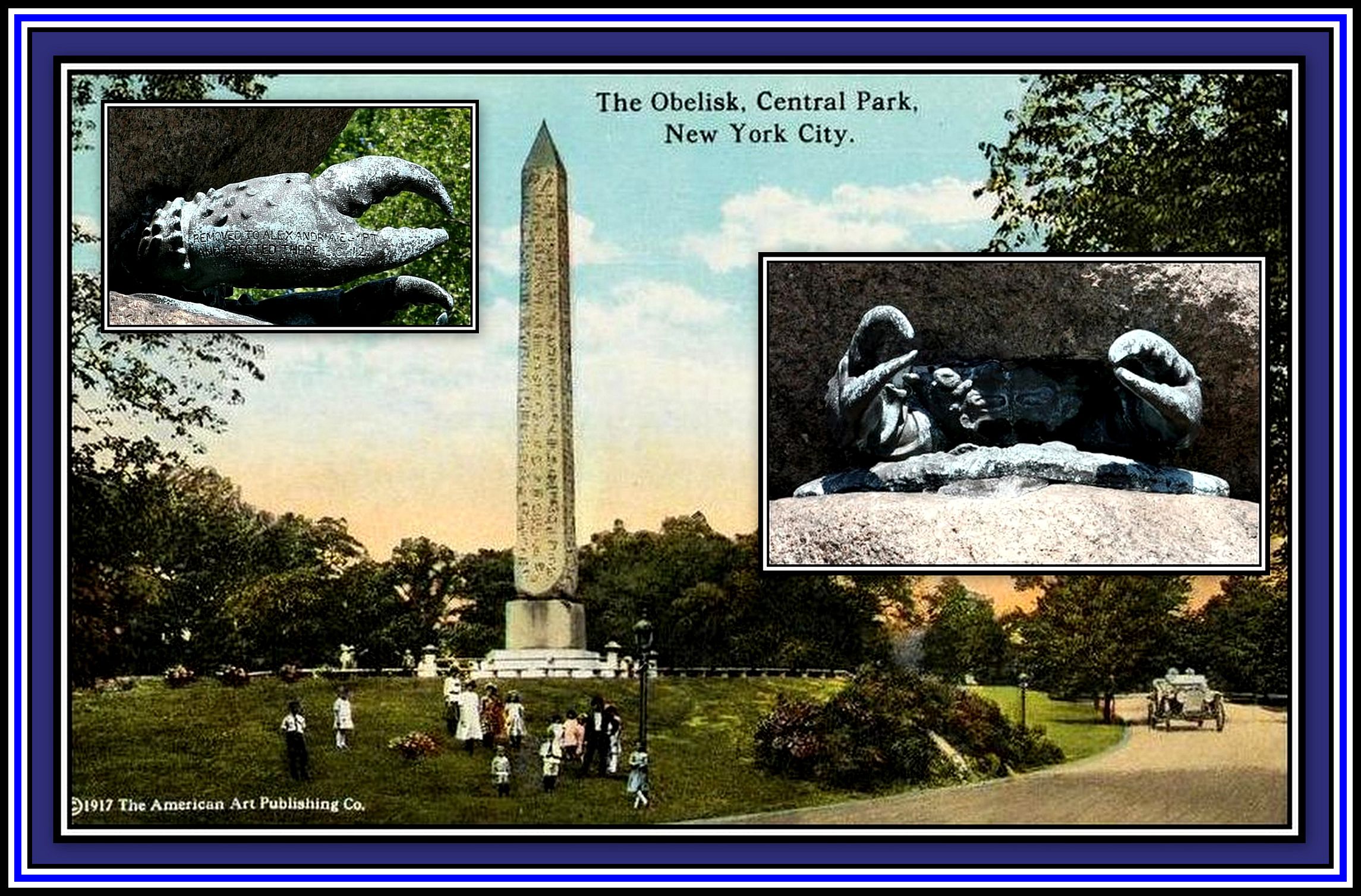

It is of interest to note that the base of the future-New York obelisk was damaged during its transportation to Alexandria. In order to help support the obelisk, four crabs were added to the base! Why crabs were chosen for this purpose is unclear. Today, only two of the original crabs and one claw remain!

Postcard of The Obelisk in Central Park, New York City from 1917 (Crabs inserted)

Postcard of The Obelisk in Central Park, New York City from 1917 (Crabs inserted)

-oOo-

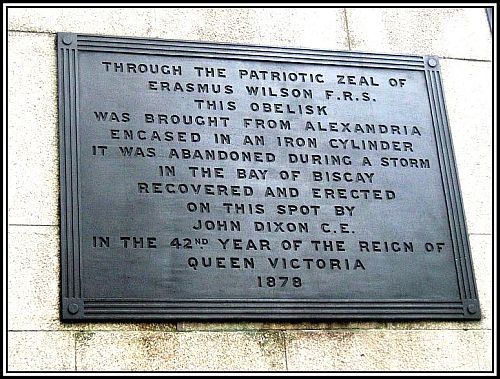

Plaque on one of the sides of Cleopatra’s Needle

Plaque on one of the sides of Cleopatra’s Needle

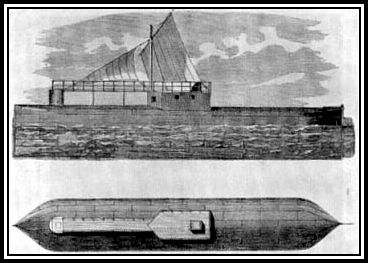

Although the British Government accepted the gift from Muhammad Ali Pasha, it declined to fund the expense of transporting it to London and the obelisk remained in Alexandria until Sir William James Erasmus Wilson (1809-1884), a renown surgeon and dermatologist, sponsored its transport to London. To achieve this aim, an iron cylinder of 92 feet in length and 16 feet in diameter, was designed by the engineer John Dixon (1795-1865) to contain the obelisk, which following certain additions, was transformed into a floating pontoon (named Cleopatra) and towed to London by a ship.

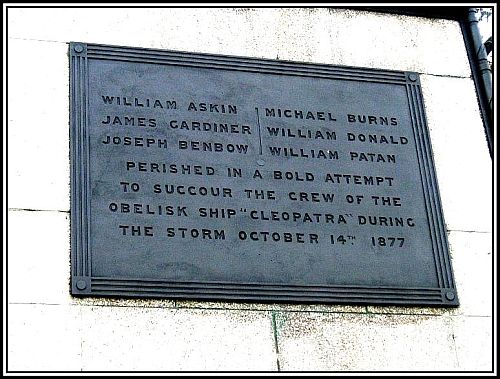

During the trip, on 14th October, 1877 and while in the Bay of Biscay, the pontoon, began to roll and eventually became untenable, causing it be abandoned. Cleopatra floated in the Bay for four days before being retrieved by Spanish trawler boats and next by the steamer, Fitzmaurice. It was towed to Ferrol in Spain where a salvage claim of £5,000 was asked and later settled at £2,000. Following negotiations, the paddle tug, Anglia, was commissioned to tow the Cleopatra from Spain to Gravesend and then up the Thames and delivered on 21st January, 1878. Its journey up the Thames was greeted by cheers from the crowds lining the route and artillery salvoes.

It was proposed to re-erect Cleopatra’s Needle outside the Houses of Parliament, but following its rejection, it was agreed to re-erect the obelisk on the Victoria Embankment, which took place on the 12th September, 1878.

-oOo-

Those who lost their lives during the rescue of the pontoon, Cleopatra, during the storm of 14th October, 1877, are remembered by a plaque on one of the sides of the obelisk. Following the arrival of the Cleopatra in London, it was sent to be broken up for scrap.

-oOo-

The obelisk is flanked by two bronze faux Sphinxes with Hieroglyphic inscriptions designed by George John Vulliamy (1817-1886) who also designed the Sturgeon Lamps lining the Victoria Embankment. The Sphinxes were improperly installed, as they both face the obelisk when they should be seen to guard it.

Sturgeon Lamp & a Faux Sphinx facing the wrong way!

Sturgeon Lamp & a Faux Sphinx facing the wrong way!

-oOo-

Postcard of Cleopatra’s Needle provided by Mr. Dave Hill

Postcard of Cleopatra’s Needle provided by Mr. Dave Hill

-oOo-

The Plinth of the Right Sphinx shows damage caused by the bomb dropped close by on the 4th September, 1917 during the First World War. Restoration work was not carried out until 2005.

The Plinth of the Right Sphinx shows damage caused by the bomb dropped close by on the 4th September, 1917 during the First World War. Restoration work was not carried out until 2005.

-oOo-

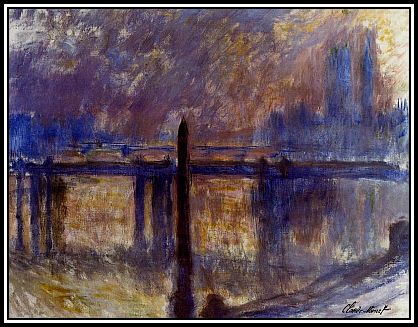

Monet: Charing Cross Bridge & Cleopatra’s Needle (1899-1901)

Monet: Charing Cross Bridge & Cleopatra’s Needle (1899-1901)

-oOo-

CHARING CROSS or HUNGERFORD BRIDGE

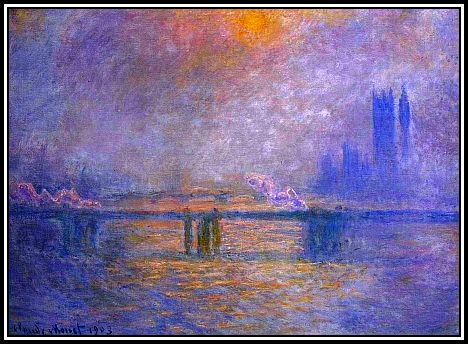

Monet: Charing Cross Bridge (1903)

Monet: Charing Cross Bridge (1903)

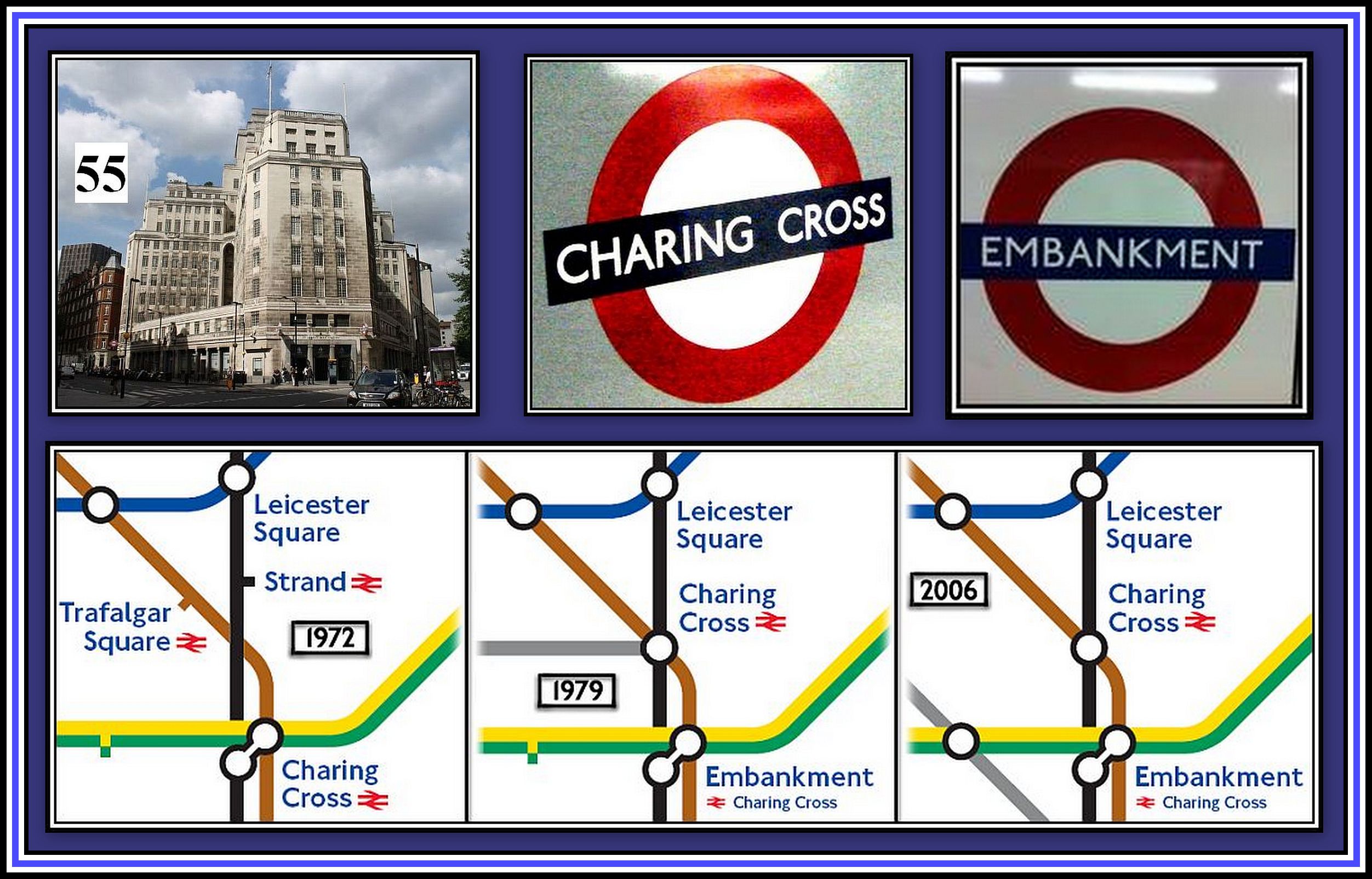

When I was young and taking walks along The Embankment with my parents, the Jubilee Bridge and the Embankment Place had yet to be built and Charing Cross Underground Station was still the long and rambling maze of corridors that stretched from Charing Cross Station & Strand beneath the ground down to The Embankment. At this time, any changes that were to come were perhaps in the planning stage and tucked away in a room at 55 Broadway.

-oOo-

Entrance to Embankment Underground Station

Entrance to Embankment Underground Station

I wonder what my father would think of the changes to this area of The Embankment. He was not one to embrace change, but I do however think that he would somewhat grudingly approve of the Jubilee Bridges addition to Hungerford Bridge. Although he admired the Thames Bridges, he found Hungerford Bridge to be very ugly and often said that it should be replaced with a more attractive structure.

Although the Golden Jubilee Bridges are not ideal, their addition does hide Hungerford Bridge and makes it less offensive to the eye!

Hungerford and Jubilee Bridges from The London Eye – photograph taken by Own Work

Hungerford and Jubilee Bridges from The London Eye – photograph taken by Own Work

I feel certain that he would not find Embankment Place to his taste. I believe that he would find it overpowering and lacking in charm. I think he would believe that it will date rapidly and most likely be replaced quickly and therefore be a waste of money! But, we will have to wait and see about this!

Embankment Place built over Charing Cross Railway Station

Embankment Place built over Charing Cross Railway Station

-oOo-

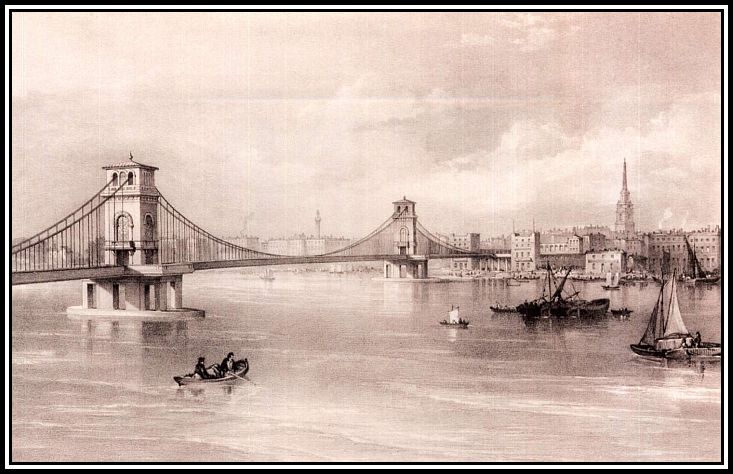

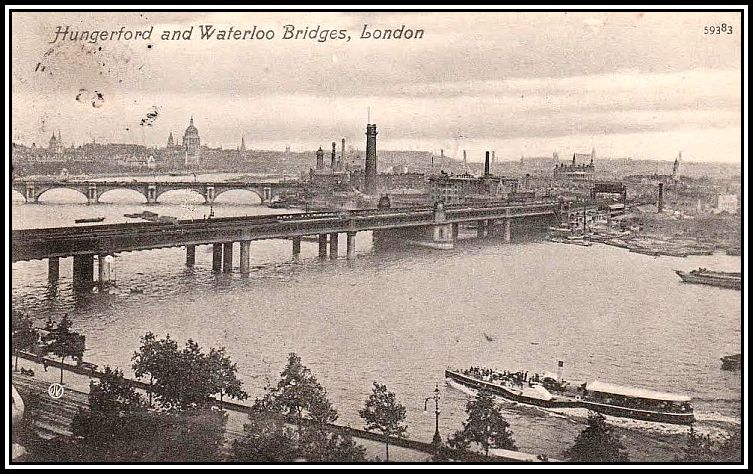

The Charing Cross or Hungerford Bridge that I knew as a child was the second bridge built to cross the River Thames at this point. The first Hungerford Bridge was a suspension bridge was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and opened in 1845. The bridge linked the South Bank to the Hungerford Market in Charing Cross.

The First Hungerford Bridge designed by Brunel

The First Hungerford Bridge designed by Brunel

The land occupied by the market was sold to the South Eastern Railway in 1862. The Company demolished the remains of the market and then built Charing Cross Railway Station on the site, which was opened for service in 1864. The Brunel Suspension Bridge was replaced with the Hungerford Railway Bridge designed by Sir John Hawkshaw. This bridge is comprised of nine spans made of wrought iron lattice girders and used the brick pile buttresses of the original bridge. The chains from the Brunel Suspension Bridge were re-used to complete the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol. Walkways were added on each side of the Railway Bridge, with the upstream one later being removed when the railway was widened.

This postcard was provided by Dave Hill

With the increase in foot traffic across Hungerford Bridge, the footbridge proved to be too narrow. In addition, its condition declined and it became dangerous to walkers. In the mid-1990s a decision was made to replace the footbridge with new structures on either side of the existing Railway Bridge and a competition was held in 1996 to find a new design and the architects, Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands and engineers, WSP Group were declared the winners. Two new 13- foot wide footbridges were completed in 2002 and named the Golden Jubilee Bridges in honour of the fiftieth anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth.

The Golden Jubilee Bridges won the Specialist category in the Royal Fine Art Commission Building of the Year Award in 2003. The design also gained a Structural Achievement Award commendation in the 2004 Institution of Structural Engineers awards and has won awards from the Civic Trust and for its lighting design.

-oOo-

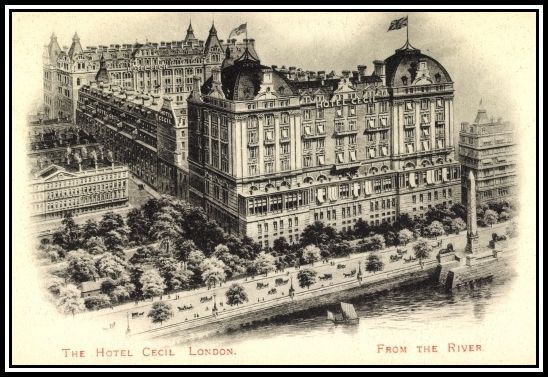

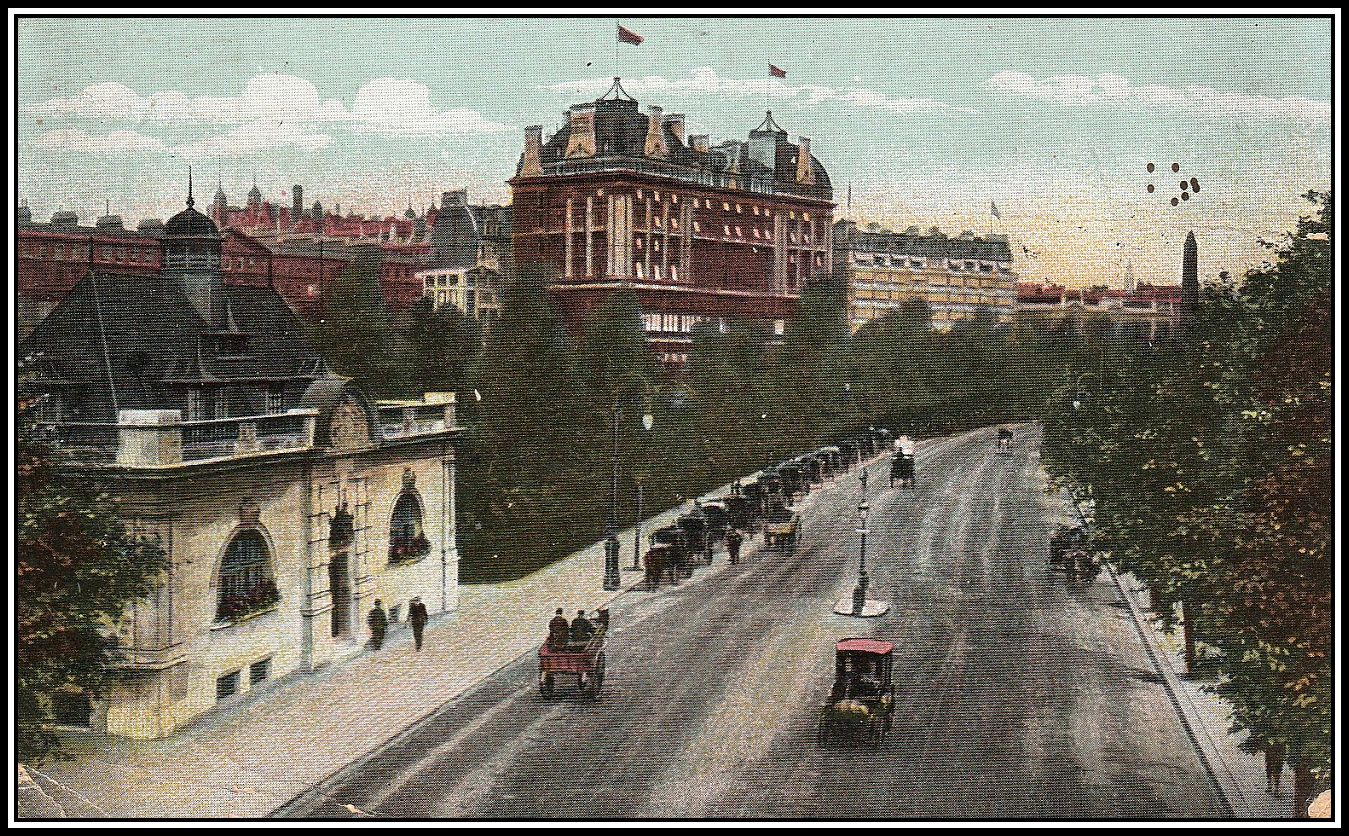

SHELL MEX HOUSE & THE HOTEL CECIL

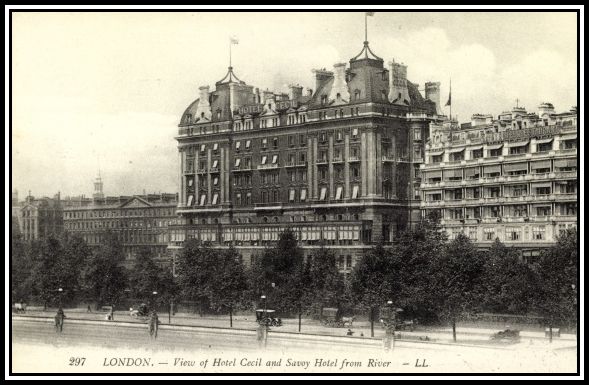

My father remembered the Hotel Cecil, and although he admired Shell Mex House very much, he lamented its demolition to make way for a new building.

The postcards of the Hotel Cecil were provided by Mr. Dave Hill

The postcards of the Hotel Cecil were provided by Mr. Dave Hill

Postcard of the Hotel Cecil, built between1890 and 1896 and demolished in 1930 to make way for Shell-Mex House

Postcard of the Hotel Cecil, built between1890 and 1896 and demolished in 1930 to make way for Shell-Mex House

-oOo-

The small white building shown on the left of the last postcard is Hungerford House. The building was used originally to house the power station when electric lighting was introduced on The Embankment and to the Savoy Theatre. Since then, the building has had other uses and today is currently a night club.

-oOo-

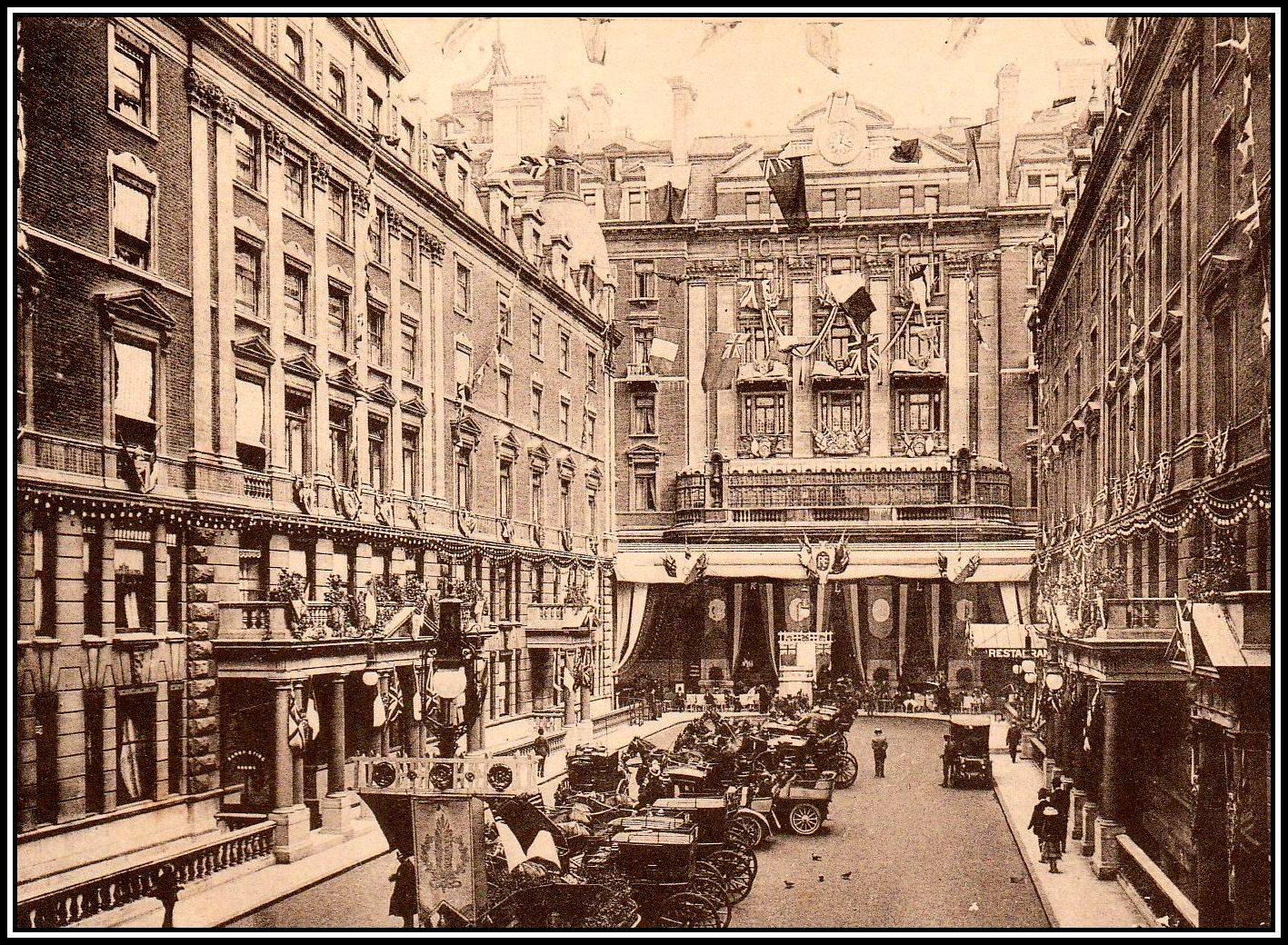

The Hotel Cecil was built between (The) Strand and The Embankment over a six year period from 1890 and was the largest in Europe at the time with over 800 rooms. Its proprietor was Jabze Spencer Balfour (1843-1916) who, in addition to being a businessman, was a Liberal Party politician. In 1892, he was involved in a scandal involving the failure of a number of companies that he controlled, which led to a large number of people losing their investments. He was convicted of fraud and sent to prison and released in 1906.

The Hotel was requisitioned for the war effort in 1917 and part of it became the first headquarters of the Royal Air Force (RAF) between 1918 and 1919. It also housed the members of the Palestine Arab delegation from August 1921 for almost a year who came to protest the terms of the Mandate for Palestine.

The Courtyard of The Hotel Cecil

The Courtyard of The Hotel Cecil

The Hotel was demolished between 1930 and 1931 although its facade on Strand remains and is occupied by shops. The Archway that once opened into the Hotel now leads to Shell Mex House.

-oOo-

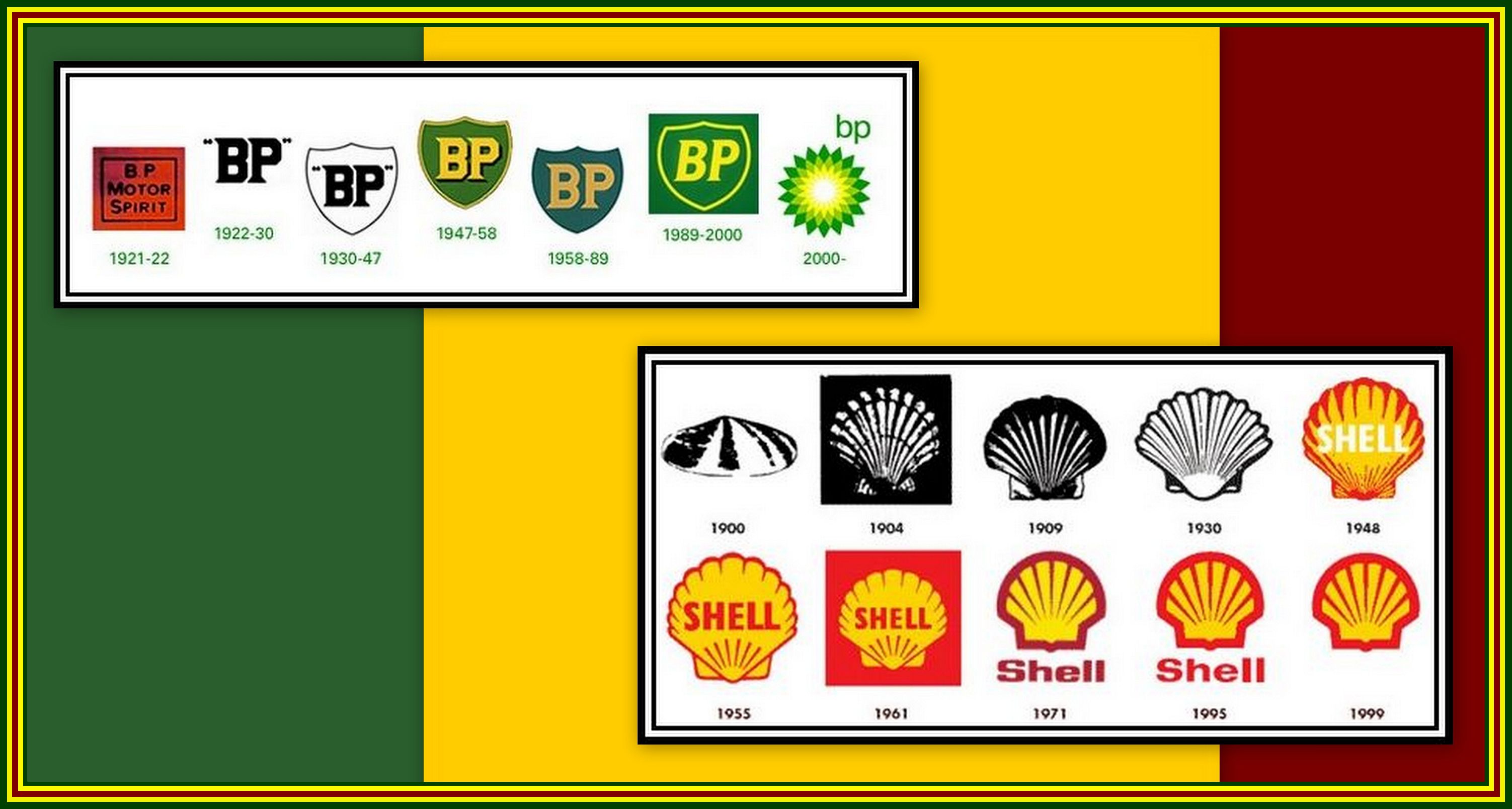

Shell Mex House was built behind the facade of the Hotel Cecil and between the Hotels Adelphi and Savoy to the Art Deco design of Ernest Joseph (1877-1960) and is a Grade II Listed Building.

The building has twelve floors plus a basement and sub-basement and boasts the largest clock in London, which has two faces, one facing the River Thames and The Embankment and the other, The Strand.

The current Shell Mex House was built in 1930-1931 and occupies the site of the Hotel Cecil

The current Shell Mex House was built in 1930-1931 and occupies the site of the Hotel Cecil

The building was built to be the London headquarters of Shell Mex and British Petroleum (BP) Limited, which was a joint venture set up Shell and British Petroleum (BP) in 1932 when the companies merged their U.K. marketing operations. In 1975, the venture was ended and the building became the London headquarters of Shell U.K. Limited until the 1990s when it passed into other hands.

During the Second World War, the building was used by the Ministry of Supply and suffered bomb damage in 1940. For a number of years until the 1970s, several floors were used by the Ministry of Aviation.

Shell Mex House, Cleopatra’s Needle & The Savoy Hotel

Shell Mex House, Cleopatra’s Needle & The Savoy Hotel

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to GO to PART THREE: THE SAVOY HOTEL

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to RETURN to PART ONE: VIEWS FROM THE BRIDGES ……. AND RIDES ON THE TRAMS

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to RETURN to A SERIES OF WALKS ALONG THE EMBANKMENT Home Page

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to GO to AN ADDITIONAL SET OF POSTCARDS OF OLD LONDON: THE EMBANKMENT by DAVE HILL

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to RETURN to the TABLE OF CONTENTS

——oooOOOooo——

3 thoughts on “THE EMBANKMENT SERIES – PART TWO”

Leave a Reply

Oh, it was great to see in this series a photo of my stretch of the Embankment with my lovely comfortable heated (yes, London’s only heated double deck PSVs from 1931 to 1951) Feltham tram on service 18 to take me home to Croydon. Lovely to board especially late evening after my parents had taken me to a theatre finishing up in Joe Lyon’s Charing Cross Corner House before braving the wind, rain and snow encountered in walking down to the Charing Cross tram stop. From the age of 8 until I was 11 the section from Hungerford to Waterloo Bridges would be my daytime home during school holidays when my mother had to work. Up on the 16 arriving about 9 with a pack of sandwiches and a drink plus a shilling until about 3.30 when she collected me for the 18 home. In those years the Feltham reigned supreme on the 16/18. If it was wet I had plenty of shelter under the bridges. There was plenty of ‘entertainment’ from watching the trains in and out of Charing Cross and the coasters, launches and barges on the Thames. Little did I know then that I would be working for the Port of London Authority from docks to river and looking after this stretch of the river’s accommodations – including the embankment’s tidal flaps that drained the rainwater from the tramway’s conduit electrical system. The most prominent legacy I left there was to license the mooring of London’s first postwar floating restaurant the Hispaniola against opposition from my boss the port’s River Superintendent & Harbour Master! But it was having some 300 trams an hour passing in both directions and the Kingsway Subway that became the greatest draw. Helping the points man at the Subway to have his lunch in his canvas hut on wet days by calling out the service numbers for him to direct the 31/33/35s into the subway without him getting wet! 5th July, 1952 was the last time I travelled from the Embankment, from Westminster to Abbey Wood on a 38 tram. After that we always travelled home by train but we still had to finish up on that dreadful 109 bus. So I have very fond memories of the Embankment from about 1948 to 1952 and then again in my 1964-69 ‘river days’ with the PLA. Studying the winter movement of tourists on it to produce a plan to increase the use of the piers after one November lunchtime coming out of the blue on to a PLA pier to find the Piermaster asleep and more tourists than I had thought strolling past !!!

I recommend anyone interested in reading about the Embankment’s history to get Robert Harley’s book published by Capital History “London’s Victoria Embankment”.

Colin: Thank you very much for writing your interesting comment. Charles

I am grateful to you for writing your comment. Charles