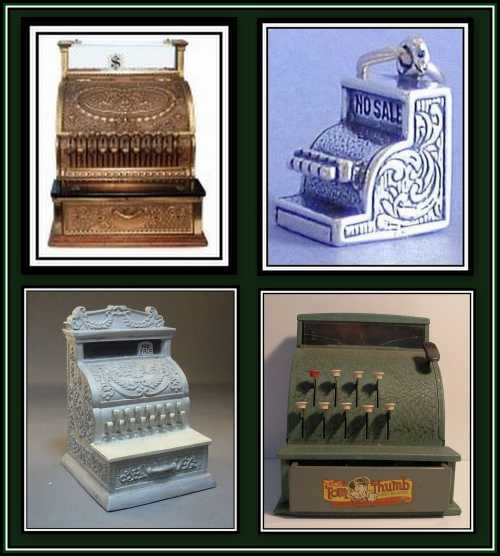

| I had a moneybox

as a child that was

in the form of a till or

cash register. It

had a few levers, which

when pressed down, rang

up an amount of money

and at the same time

caused a drawer to

open. Mercifully, it also

had a No Sale lever

that allowed the opening

of the drawer

without an intention of making

a deposit. It would

therefore seem easy for

me to get the necessary

money to buy a ticket on

the following Monday to

see How to Marry a

Millionaire were it

not for the fact that the

cupboard, or rather the

drawer, was bare. Obviously

I had spent what money I

had. I was now faced with

having to get nine

pence by Monday, a

mere three days away! If

I wanted to get to the

cinema by bus, then

another three pence would

be needed for the ride

there and back on the

number 653

trolleybus. The total

amount required was

therefore one shilling.

By today’s

standards, this amount is

nothing – five

new pence – ten

cents – a dime!

However in 1953, this

amount actually bought

something and was, to

a child, no small amount.

Still, never say die!

I had the weekend to find

the money.

The reader

might be wondering why I

did not ask my parents

for the money. I did not

want to chance this

at this time,

as I knew full well that

my mother would not allow

me to go to Hackney alone

and since neither she nor

my father would be able

to accompany me as they

would be working, I could

not go. The reader

should remember that her

reticence regarding Hackney

was not as a result

of the Borough being

especially dangerous, but

was rather a matter of my

age. She undoubtedly

would have felt that I

was far too young to go

alone, thereby ending any

chance I had of going.

No, I had to come up with

the money myself and then

sneak away, see

the film and return home

with my parents being none

the wiser. Of course,

I reasoned, if I failed

to come up with the

necessary money, I

planned to throw caution

to the wind since I

had nothing to lose and

ask them for the money.

Meanwhile,

I had to think and come

up with a way to get the

necessary shilling. I

knew on that Friday

afternoon that it

wasn’t going to be

an easy task, but I was driven.

I had to see the film

and so set about

thinking of a way to come

up with the money. After

a while, an idea came

into my mind that most

certainly would have

given me to the necessary

money. I would have

pursued this idea to the

end were it not for the

fact that immediately it

came into my mind, it

caused me to shudder and

to feel instant shame.

The reader may agree that

a conscience puts

paid to many a good

plan! Meanwhile,

I had to think and come

up with a way to get the

necessary shilling. I

knew on that Friday

afternoon that it

wasn’t going to be

an easy task, but I was driven.

I had to see the film

and so set about

thinking of a way to come

up with the money. After

a while, an idea came

into my mind that most

certainly would have

given me to the necessary

money. I would have

pursued this idea to the

end were it not for the

fact that immediately it

came into my mind, it

caused me to shudder and

to feel instant shame.

The reader may agree that

a conscience puts

paid to many a good

plan!

My mother

was a great believer in

insurance. Every other

Monday morning, the

insurance agent called to

pick-up the premiums.

This was common-place in

those days and these men

would walk from shop to

shop and house to house

collecting a small amount

of money from each. I

don’t ever recall

hearing of any that were

robbed, but I suspect

some were. My mother

would put the required

amount into a money

bag that she had

received from the bank

whenever she collected change

for the shop from

them. She kept the bag in

the lower left-hand

drawer of the sideboard

in the parlour so

as to have easy access to

it once the insurance man

came to call.

I was

brought up to be honest.

This was drummed into

me as a child by my

mother. She said that

stealing was a crime and

that once a person

committed a crime, they

lost their good name. And

once lost, this was

something that could

never be got back. To her

and to most people of her

generation, having a

good name was vital

to their existence. On

that Friday afternoon, I

had thought about her

little stores of money

about the house and of

the insurance money in

the lower left-hand

drawer of the sideboard

and wishing that I

could help myself to

some. Despite a strong

wish to lift some since

I really wanted to go to

the pictures, the thought

of losing my good name

was too awful to bear.

It caused me to shudder

and to feel a sense of

shame. I was left with

the knowledge that if I

were to go to the

pictures on the following

Monday, then I would have

to come up with it

another way. As I said, a

conscience and a sense

of doing right can

often seem to take the

joy out of life.

On the

Saturday, I remember

trying to be, what I

thought, was especially

helpful. I offered to do

things about the house in

the hope that it might

bring me some pennies,

but what I was

offering to do turned out

to be the jobs that I was

supposed to do! In

desperation I offered to

make some tea for my

father in the afternoon.

I thought that this might

soften him up and

that it might cause him

to give me a reward.

Tragically, my tea never

came up to my

father’s expectation

and he was furious that his

son was such a

failure when it came to

this art! Following

my dismissal from the

kitchen, I went up the

Waste, the market on Whitechapel

Road, in front of the

London Hospital. Surely

someone would have

dropped a penny or two

and I might then be lucky

enough to pick it up. I

remember that I had once

found a sixpence as

I was crossing Brady

Street and hoped to

be as lucky again. Alas,

there was no treasure

trove on the streets of Whitechapel

on that afternoon. I

went to Paul’s

stall where he gave

me some money to buy him

a cup of tea and a drink

for me. I remember asking

the cafe owner if he

would give me the cost of

the drink rather than the

drink itself. Either he

did not hear or he chose

not to hear me and I left

with a cup of tea for

Paul in one hand and an

orange drink for me in

the other. Where were the

streets paved with gold

that filled story books,

I wondered?

The Waste

Tomorrow

was Sunday and I would

then be desperate.

However, what is it that

they say? Something about

it is always darkest

before the light?

My father

had the habit of disappearing

periodically when I

was a child. Quite

suddenly, for what would

seem for no apparent

reason, he would take

off and be gone for

a week or so. Not only

did he go, but would do

so without telling my

mother where or why he

was going. During his

absence, we sat and

worried, not knowing

where he was. All we knew

that he had left, taking

all of the available

money with him and was

obviously enjoying

spending it on drink for

himself and others.

My father

would return as suddenly

as he left. Despite my

mother’s demands, he

never said where he had

been. He returned home

without any of the money

that he had taken from my

mother’s store

that she kept in a cash

box for food and

sundry expenses. Should

this amount prove too

little for his needs, he

would pawn one of his

suits. Whenever he ran

off, my mother always

checked behind a large

mirror in the parlour,

and invariably

found a pawn ticket.

Once such a ticket was

found, we knew that my

father would not be seen

for a week or so.

EastEnd

Pawn Shops

The

Dundee Arms was once a

Pawn Shop

My

father’s refusal to

tell my mother where he

had been while away both

frustrated and annoyed

her. My mother was hurt

and never understood why

my father needed to run

off, giving no

thought to us. Whenever

she would ask where he

had gone or if he was

aware that he had left us

with money for food, he

would sit in his chair

and remain silent. He

never offered us any

explanation to account

for this behaviour.

When I was

a little older, my

parents gave up the pie

and mash business and

my father went to work

for British Railways.

Unfortunately, a change

in profession did not

cause him to change his

way and he still

continued to ran off periodically.

While my parents had the pie

and mash shop, my

mother maintained the

business in my

father’s absence and

opened as usual.

Following our move, she

was no longer chained

to the business and I

recall that on one of my

father’s excursions,

she decided to see if he

had gone to visit some of

his relatives who were

living in South

London. Although my

mother liked very much my

father’s father and

stepmother, she did not

like his

stepmother’s

children from her first

marriage.

My father

had a half-sister,

named Florence, known as

Florrie, who had led a

life dedicated to fun

and frivolity and was

renowned for her poor

taste in men. She and her

husband of the

time, a man known as Wagie,

suffered from the

constant need to move

home since neither worked

with any frequency and

had problems paying the

rent. As soon as they

scraped together any

money, they would spend

it on drink and betting.

My mother never warmed

to Florrie and we

only saw her on rare

occasions – very

rare occasions.

I cannot

remember the reasoning,

but once when my father

had taken off, my

mother seemed convinced

that he was billeted with

these family members. I

am unsure how, but my

mother had obtained

Florrie’s current

address and she was

determined to find out if

her hunch was true. And

so my mother and I

crossed the river and

went to Camberwell, which

was where Florrie and Wagie

lived.

Camberwell

Green

I remember

getting off the bus at Camberwell

Green and walking

along an endless number

of little streets before

finally arriving at the

house. My mother knocked

at the door. Florrie

opened it and appeared

somewhat frightened.

Immediately, she began

making excuses in a very

nervous voice to account

for my father’s

presence in her home. My

mother, with me in tow,

entered the house and

found my father sitting

at the kitchen table

alone. Apparently Wagie

was somewhere else. We

did not miss not seeing

him. My mother was

furious both with my

father and with Florrie.

Both sat at the table

with their eyes down and

said nothing. I remember

my mother asking Florrie

if she was not aware that

the drinks that my father

had bought for her had

been purchased with money

that should have bought

food for me! Florrie had

sense enough not to

answer, but continued to

stare at her hands folded

in her lap.

Although

this situation may sound

Victorian and

melodramatic, it was

nonetheless true, I am

sorry to say. Once my

mother had finished

expressing her opinion of

both Florrie and my

father, she announced

that she and I were going

home. My father, still

looking sheepish, got up

and spoke for the first

time. He said, not daring

to look at either of us,

that he would accompany

us home. Prior to sweeping

out the door with my

silent father and I, my

mother turned and advised

in quite strong terms

the pathetic Florrie

to discourage any such

future visits from my

father. I don’t

recall ever seeing my half-aunt

ever again. Although

this situation may sound

Victorian and

melodramatic, it was

nonetheless true, I am

sorry to say. Once my

mother had finished

expressing her opinion of

both Florrie and my

father, she announced

that she and I were going

home. My father, still

looking sheepish, got up

and spoke for the first

time. He said, not daring

to look at either of us,

that he would accompany

us home. Prior to sweeping

out the door with my

silent father and I, my

mother turned and advised

in quite strong terms

the pathetic Florrie

to discourage any such

future visits from my

father. I don’t

recall ever seeing my half-aunt

ever again.

Although

my father was caught at

his half-sister’s

home, a place I am

sure that he had gone to

numerous times before, he

did not change his

ways. He continued to

disappear for many

years to come.

With time

and the ability to earn

sufficient money to take

care of our immediate

needs, my mother

eventually gave up

worrying about him. Once

she reached this

position, whenever he went

away, she would shrug

her shoulders and say let

him get on with it.

However, while I was

still very young, my

mother was shaken

whenever such a disappearance

occurred. His

behaviour hurt her very

much and she could never

understand why he went.

Despite this, and being a

practically minded woman,

my mother knew that she

had to take charge and

see that we were fed and

clothed and had a roof

over our heads since

she could not rely on my

father to help provide

for us at all times.

Fortunately, early in my

mother’s married

life, she realised that

she had married a man who

might be gone at any

minute. As a result

she sensibly took

control, and thanks to

the good habits learned

as a girl, she was able

to take care of us while

my father was away.

When my

mother was a child, she

lived in one of the

poorest areas of the East

End of London. At

that time, people earned

very little money and

learned to live on very

little, or, as they used

to say, lived from

hand to mouth. Many

families in Bethnal

Green had to rely on

the goodwill of the

various Missions and

Societies that

existed, such as

the Salvation Army, to

feed them when they were

unable to make ends

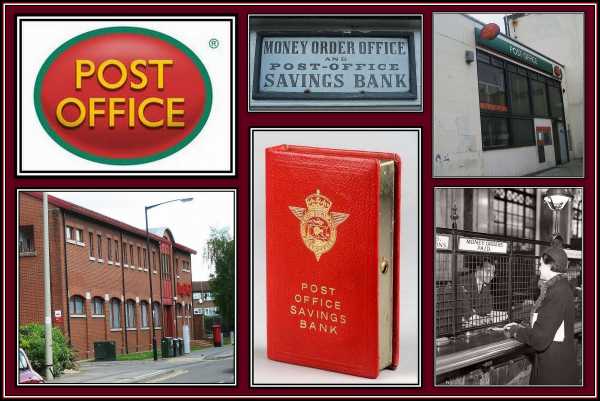

meet. At that time,

very few people were ever

able to save any money

and no one had a bank

account. Once things

began to improve,

whenever working people

were able to scrape

together some meagre

savings, they began to

deposit it in an account

at the Post Office.

Here their money was safe

and it earned interest,

albeit little by

today’s standards.

When I was

a child, the Post

Office was still the

primary place where

savings were kept. I

remember my mother taking

me to the Post Office in

Aldgate at a very

young age to open a

savings account. I was

always very happy when it

came time for me to empty

my moneybox of the

pennies, threepenny

pieces and any other

coins that I had been

lucky enough to save. I

would count the coins and

put them into various

piles and note how much I

had to take to the Post

Office for deposit.

It was with great pride

that after standing in

line at the Post

Office for what

always seemed to be an

eternity, I put my

coins on the counter

along with my book and

waited for the man to

check the amount. Once

this was done, he wrote

the amount in my book and

then calculated the new

total. He then returned

the book to me and, after

thanking him, I would

walk with pride out of

the Post Office.

At that

time, very few, if any,

had cheque books. Most

things were bought on a

cash basis or on hire

purchase, which was

just beginning to grip

the nation. Credit cards

had yet to be used by

working people.

Fortunately

for us, my mother had

developed the habit of

saving. Although she was

unable to save very much

on a regular basis, what

she did save added up

and proved to be a

life saver when

needed. My mother wisely

did not share the

knowledge of this hidden

account with my father

and kept it safe for use

only in the case of a

rainy day. When my

father disappeared with

our available cash, we

did not starve since she

would draw on her emergency

funds. Having had a

difficult childhood

herself with too little

to eat and with too

little money, she knew

how to stretch a

shilling to its

utmost, thank goodness.

In

addition to having an emergency

fund, my mother also

had small stores of money

about the house. She had

learned to do this from Bubba

and Zayde when

she was a child. They, as

I have said came from

Russia, and had

undoubtedly been victims

of discrimination. As a

result of this, they, and

many other Jews, knew

that they might have to run

at any minute in

order to save themselves.

This meant leaving their

home and their

possessions behind and

taking only the clothes

that they wore. Knowing

this, they were certain

to keep a coin or two in

the pockets of their

coat, trousers and

handbag. My mother has

noticed this and asked Bubba

why she did this. My

mother took heed of her

explanation and adopted

the custom for the

remainder of her life. I

have to admit that

whenever my father flew

into a drunken rage when

I was a child and we fled

the house in fear of

our lives, neither of

us left the house penniless!

The reader might be

amused to learn that the

odd coin is found in

every coat that I own as

well as in all other

garments that have a

pocket. One never knows

when one might have to

run!

Anyway,

despite my being brought

up to save money and

having a Post Office account,

I found myself with what

is now called a cash

flow problem. I had

no liquid cash, as

my empty moneybox proved

and I had no obvious

means of making the

necessary money. So how

was I going to get hold

of a shilling?

The reader

may be asking wasn’t

it now the time to throw

myself on the mercy of

my parents and ask them

for the money? It was

still on Sunday. I had

the whole of the day yet.

Perhaps some miracle

would happen. Perhaps

some way might be found

yet.

What

was I saying earlier

about it is always

darkest before the light?

When I was a child,

the public houses of

Britain opened for the

licensed drinking of

alcoholic beverages at

noon on Sundays. And a

short time after the

doors were opened to the

welcomed public, my

father would cross Cambridge

Heath Road and enter The

White Hart public

house and imbibe a few

bevies. Often he

would drink just enough

to cause him to feel

happy and return home in

a jolly mood.

Other times he would

return having drunk too

many drinks and would be

in a fighting mood and

we would be ready to run.

On this Sunday, and I

thank God for this still,

he returned home in a

particularly jolly mood.

My father never gave me

any pocket money. After

all, he needed his money

to buy drinks for himself

and total strangers,

didn’t he? My pocket

money came from my mother

and she had strict ideas

about how and when it

should be spent. Although

she had my best interests

at heart, I found her

demands to be somewhat

excessive at times. There

was one good thing about

my father when he was

drunk and in a jolly mood

and this was that he

would become generous,

both with words of

affection and with the

giving of money! What

was I saying earlier

about it is always

darkest before the light?

When I was a child,

the public houses of

Britain opened for the

licensed drinking of

alcoholic beverages at

noon on Sundays. And a

short time after the

doors were opened to the

welcomed public, my

father would cross Cambridge

Heath Road and enter The

White Hart public

house and imbibe a few

bevies. Often he

would drink just enough

to cause him to feel

happy and return home in

a jolly mood.

Other times he would

return having drunk too

many drinks and would be

in a fighting mood and

we would be ready to run.

On this Sunday, and I

thank God for this still,

he returned home in a

particularly jolly mood.

My father never gave me

any pocket money. After

all, he needed his money

to buy drinks for himself

and total strangers,

didn’t he? My pocket

money came from my mother

and she had strict ideas

about how and when it

should be spent. Although

she had my best interests

at heart, I found her

demands to be somewhat

excessive at times. There

was one good thing about

my father when he was

drunk and in a jolly mood

and this was that he

would become generous,

both with words of

affection and with the

giving of money!

My father

was never able to eat his

Sunday lunch since he was

generally full from

drinking. He would start

to eat, but soon push his

plate away barely

touched. By now he was on

the verge of falling

asleep and was at his

most vulnerable. This was

my window of

opportunity and I

seized it with both hands

and asked him for

…… a penny.

His eyes opened and I

remember that he

immediately put his hand

into his pocket. This

action disturbed his

equilibrium and he began

to fall sideways. As he

did I jumped up and ran

to save my dear Daddy!

To steady himself, he

placed a

hand on my shoulder and

with his other hand, he

dragged out the coins

from his pocket and

dropped them on the

table. This action seemed

to exhaust him and he

remained still for a

minute or two. Suddenly,

he turned and looked at

me and examined my face

in depth. This was now my

great chance. I looked

back at him and tried to

appear as charming and as

sweet as I possibly could

and gave him a loving

smile. I must have

succeeded, as immediately

tears to filled his eyes

and, what I can only

assume was guilt, seized

hold of him. At such a

time as this, I suspect

that all of his past crimes

returned to him. As

the tears began to slip

down his cheeks, he grabbed

me and brought me close

to him. He kissed me a

number of times on the

cheeks and between sobs

told me how much he loved

me. While I was being

grabbed, held and kissed,

I caught a glimpse of my

mother as she raised her

eyes to heaven, as if to

say so why don’t

you show it when

you’re sober? My

father was now in a

fully-fledged sentimental

state and, after

releasing me a little so

that I could once again

breathe, he began to tell

my mother and I again and

again, between his tears,

how much he loved us and

that we could have

anything he owned. The

last part of his remark

was redundant since the

poor man owned

practically nothing. This

was because whenever he

did have something

he quickly drank away it

away in the company of

his cronies. Despite

this, I took him up on

his offer and once again

asked him for a penny.

Slowly and

purposefully, he reached

out took up some of the

coins on the table and

next pressed them into

mine. He repeated this

gesture several times. By

the time this display of

love was over, I

had every

coin that was

in his pocket – coppers

(pennies), ha'pennies

(half-pennies), two bob

bits (florin, two

shilling pieces), tanners

(sixpences), thrupenny

bits (three pence coins) and a

couple of

half-a-dollar pieces

(half-crown).

This was quite a

windfall. Needless

to say, I was overjoyed

to receive such wealth

and I was most grateful

to my Daddy for

his generosity.

While my

mother helped my father

up the stairs to bed, I

counted my money and

quickly hid sufficient

monies for my needs. I

now had the necessary

capital to finance the

purchase of a cinema

ticket as well as for the

bus fare, there and

back, and for an ice

cream to be enjoyed

during the interval prior

to the start of the big

picture. Upon my

mother’s return to

the table, she asked me

how much the old sod had

given me. I told her

truthfully the amount

that now stood in proud

piles before me on the

table. She said that I

should save the major

part and put it in my money

box since you never know

when you might need it! She

said that I could keep a

small amount and

spend it as I chose. I

thanked my mother for her

sound advice and part of

me admired her for her

concern for that rainy

day, which would one

day turn up. I knew then

that she was right to

suggest that I save my

great windfall, since

one never knew if, or

when, it might occur

again. Knowing my

mother’s ways had

caused me to sequester

away the necessary

funds to support my

excursion without her

knowledge. This was vital

since the desire to go to

the pictures the next day

had been so strong and

could not be resisted. I

am still not proud of my deceit,

but desperate situations

require desperate

measures, don’t

they?

FOOTNOTE

The City

of Vienna

As I said,

my father did not offer

any heart-felt apologises

for his actions to either

my mother or me while I

was young. Upon his

return, he was always

penniless and extremely

quiet. He offered no

explanation, no excuse

and no apology. On

occasion, when he was

drunk, he might weep and

beg forgiveness for

his past actions. Such weeping

and begging did

not take place when he

was sober. Regardless of

these drunken displays of

regret, he continued to

disappear at periodic

intervals.

It

wasn’t until years

later, once I had

finished college and was

living abroad, that my

father finally admitted

to his poor behaviour.

This came in the form of

a letter that he had

written to me while I was

Vienna. I was

still young at this time

and at the beginning my

career. I had gone to Vienna

to give a presentation at

a scientific meeting.

Regrettably, the conference

planners had arranged

for me to stay at a large

and fancy hotel in the

centre of the city. They

obviously had mistaken me

for a wealthy professor

with unlimited funds and

a wish to see and be

seen. Although my

fare and conference fees

were paid for by my

university, I was

expected to pay the costs

of the hotel myself.

Unfortunately, my

position was such that my

monthly salary was small.

After looking at this

glorious hotel, it did

not take me long to

realise that I could not

afford to stay there.

What I needed was a

simple pension, a

small hotel without

superfluous opulence. I

promptly cancelled my

reservation and soon

found a charming little

hotel with kindly staff

where I had an enjoyable

stay.

The Sacher

Hotel

Unfortunately,

my father believing me to

be staying at that grand

and glorious hotel in Vienna,

addressed his letter to

me, care of the hotel. It

took about three months

for the letter to be

returned to him and then

forwarded to me. I felt

very sorry for him once I

finally read the letter

since he must have been

under the impression that

I had ignored its

contents. My father wrote

me a charming letter that

contained his regrets for

his past behaviour. He

said that he felt shame

when he thought about the

times that he had

returned home drunk. He

apologised for the times

when he disappeared and

for the times that he

missed during my

childhood.

My

father had written many

letters to me while I was

away at college and when

I lived abroad. He mostly

took dictation from

my mother, but he did add

little bits himself.

According to my father,

he left school without

being able to read or

write. He said that he

was unable to concentrate

on any lesson other than woodwork

and preferred to play

truant. It

wasn’t until he left

school when he was

fourteen years of age

that he taught himself

to read and write. He

said that he did this by

copying words and

sentences from the

newspaper. Although his

sentence construction and

spelling were not perfect,

his letters were understandable

and a delight to read. I

was always appreciative

of them and understood

the effort that they took

to write. My

father had written many

letters to me while I was

away at college and when

I lived abroad. He mostly

took dictation from

my mother, but he did add

little bits himself.

According to my father,

he left school without

being able to read or

write. He said that he

was unable to concentrate

on any lesson other than woodwork

and preferred to play

truant. It

wasn’t until he left

school when he was

fourteen years of age

that he taught himself

to read and write. He

said that he did this by

copying words and

sentences from the

newspaper. Although his

sentence construction and

spelling were not perfect,

his letters were understandable

and a delight to read. I

was always appreciative

of them and understood

the effort that they took

to write.

As a

result, I was greatly

appreciative of the

letter that he wrote to

me while I was in Vienna.

It must have not only

taken him a great deal of

time to write, but also a

great deal of pain and

regret. I still have his

letter. I keep it along

with a number of other treasures

in what was once his cufflink

and stud box. His

letter went a long way

to helping me forgive

my father for his past

actions. Every now and

again, sometimes when I

notice his box, I open it

and take out his letter

and reread it and

experience the

bitter-sweetness of its

contents once more.

Click on the picture for

a video clip

I

would like to thank Mr.

Brian Hall and Mr. Kevin

Wheelan for their

kindness in allowing many

of their pictures to be

reproduced here.

|