MEDICINE & THE

KID FROM LEFT FIELD

JAMES & THE CASE OF THE UNANSWERED QUESTION

|

| |

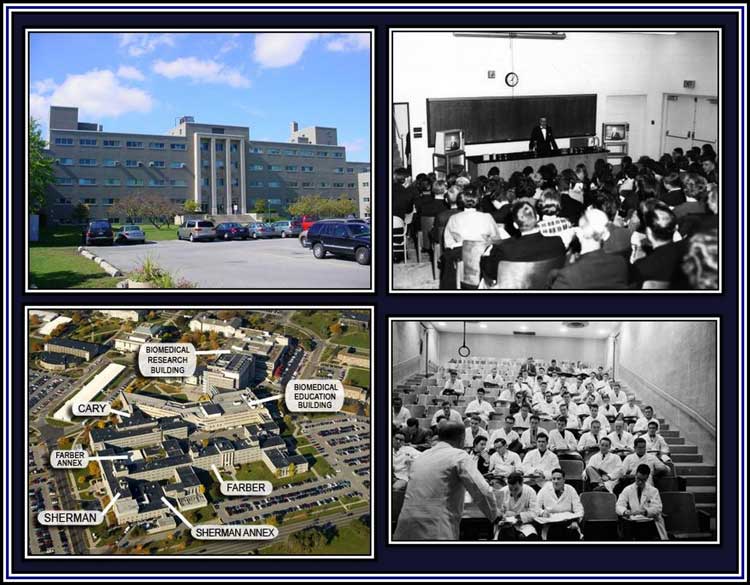

I sat there stunned. I could not believe what I saw on the screen in that most uncomfortable of lecture halls. There, up on the screen, for all to see, was a very old slide of extremely poor quality. However neither age nor lack of quality could hide what it showed from me. Up on the screen was the answer to something that had bothered me since childhood. Here at last was the solution to The Case of the Unanswered Question. In pure Perry Masonfashion, the culprit had finally been exposed for everyone to see.

|

| |

|

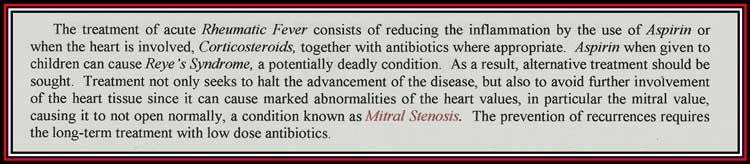

The lecturer was talking about the salient features and Pathophysiology of Rheumatic Fever and making it sound very boring. The fact that Rheumatic Fever was no longer seen often in the United States obviously escaped the attention of those that decided the curriculum, however it once afflicted many children and took the lives of a large number each year. As a child my father suffered with this illness. He believed that it left him with a mild heart condition, which I was never totally convinced of even as a child. I suspected that we were being taught about an illness that most of us, if not all of us seated there in that lecture hall, would never see was because its cause and course were well understood and illustrated a major approach to medical treatment. |

| |

|

| |

Rheumatic Fever is a nasty illness that can follow the failure to treat a sore throat. It seems that the body starts reacting to itself. Imagine that! I was later to learn that there are a whole host of illnesses where the body reacts to itself and causes havoc and misery for the sufferers.

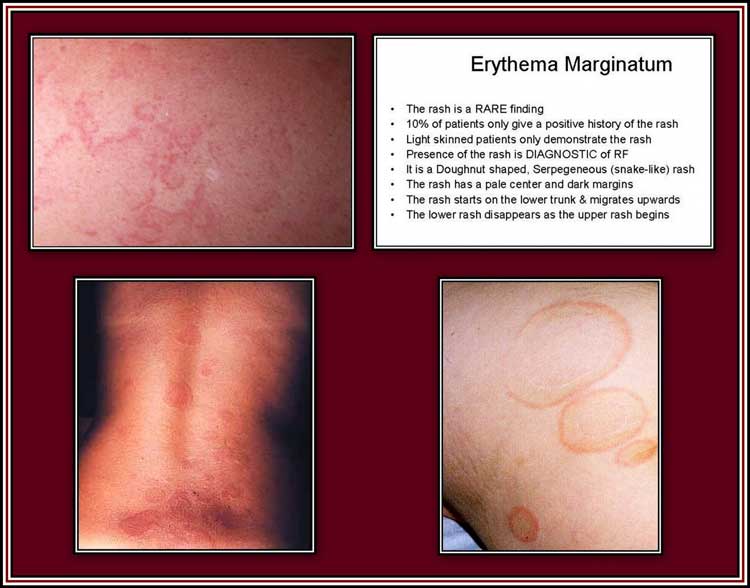

Anyway, there, up on the screen was a slide showing the rash that James suffered with! Apparently it was called Erythema marginatum. This is a rash that begins on the trunk or arms and spreads to form a snake-like ring with a clearing in the centre. There it was for me to see! I could not believe my eyes. I think I sat bolt upright and may have given out a little yelp or cry. Whatever I said caused those about me to also sit up, which was followed by a series of groans and irritated movements rippling through the auditorium, as others were roused from their slumbering. The sudden activity caused the lecturer to realize that there were others in the hall besides himself and caused him to drop the notes that he was reading from.

Some bright spark in the audience asked for the lights to be turned on and once the room was lit everyone burst into conversation. It was soon learned that I was the cause of the commotion. Since I was a lot older than my classmates, I was secure enough not to care if I became unpopular with them for causing an interruption to the boring flow of the lecture. However, I felt that they might be interested in knowing why the class had come to a standstill so I stood up and began to explain my yelp or whatever. Meanwhile the lecturer was in total chaos at the front of the class trying to sort out his notes. |

| |

|

| |

|

| My Class at Sir John Cass Foundation School |

| |

I told the class about James, the little boy who I knew back in London during the early 1950s and how he was always ill and away from school. I described his appearance in glowing medical terms and then gave them the piece de resistance and told them about the rash! By now the lecturer had regained his composure and was listening attentively. Perhaps glad of the break, he seemed to go off into a trance for a minute, but at my mentioning of the rash, he returned to reality and looked at me with renewed admiration. It seems that I was the only one in the room that had actually seen a case of Rheumatic Fever! How about that for fame! The next year when I started my clinical years, I was often consulted on the condition. It is typical of many medical students to over-diagnose a condition or to hear all kinds of additional sounds when examining the beating of a heart, which to the more mature simply prove not to be present. As a result, multiple cases of Rheumatic Fever amongst other illnesses were forever being diagnosed by the overly zealous members of my class.

Following my discourse, the lecturer decided we needed a break. The break found me encircled by the more nerdy students who did not really want to hear more from me, but rather wanted to tell me what they had seen when observing in either their father’s, mother’s, uncle’s, or whatever’s clinic. I was supposed to be interested in their yappings.

Once back in class, with the lights dimmed, I was feeling sleepy again. This was helped by the eating of a chocolate bar during the break. Soon the repetitive groans of the lecturer caused my eyelids to become heavy. Soon my mind began to wonder. After a few minutes, I left the lecture hall and found myself wandering back to my early school years and to the people who shared my classes at that time. |

| |

As I said earlier (see An American in London) James was, as far as I can remember, amiable enough. He was quiet and easy to get along with and, as far as I can remember, was quite studious. I cannot recall his making his opinions known often although he rarely disagreed with games chosen and seemed to like most of the things that the rest of us did. What separated him from the class were two things: besides being quiet and a fellow of few words, he was often absent from school due to illness. As I said earlier (see An American in London) James was, as far as I can remember, amiable enough. He was quiet and easy to get along with and, as far as I can remember, was quite studious. I cannot recall his making his opinions known often although he rarely disagreed with games chosen and seemed to like most of the things that the rest of us did. What separated him from the class were two things: besides being quiet and a fellow of few words, he was often absent from school due to illness.

It was not that he was a weakling, but rather he suffered with shortness of breath. He could run and play football, but he would soon have to stop to catch his breath and forced to sit on the sidelines. No one thought this strange in those days. This was a time when many kids were not as robust, or as noisy, as they are today. We were a class born during the war and although most of us had no memories of bombs and shelters, we were aware of shortages and the general difficulties of life at that time. I remember our class had several kids that were often ill so James was not considered odd in any way. |

| |

| Once such girl, I recall, was Maureen Curry. She was slightly older than me, very pretty and wore her brown hair in tight plats. I liked her. She lived somewhere along the Commercial Road in Stepney and took the 535 Trolleybus home, while I took the 653, which went along the Whitechapel Road. I regretted not living along the Commercial Road, as I really would have liked to take the bus home with her each day. She had a nice smile. Most of the boys in the class liked her, and although she smiled at them too, I always felt that she gave me a special smile. I smile now at this sign of conceit. She was friendly, but not overly so, and would spend most of the playtimes sitting in the playground talking to her friend. Her friend was, in my opinion, a hag, a word I remember hearing used in a play on the radio. I have always liked this word and it has aptly described so many nasty women and girls that I have since met. |

| |

|

|

Maureen Curry, back row, on the left; me, middle row, second from the end on the left |

| |

| Maureen was very sweet natured and always spoke to me whenever I could tolerate the company of her friend. Sadly, the two were inseparable and one had to tolerate the presence of the hag whenever one wanted to spend time with Maureen. She always smelt so nice. I am sure that this was the perfume of the scented soap that she used since fabric softeners had not been thought of at that time and young girls were not permitted to wear scent to school.The chances were that her soap was either Knight's Castile or Lux since these were the most popular at the time and were used according to newspapers and magazines by film stars. Sadly, I can’t remember any details of my conversations with her, but I do remember enjoying them and I do recall that she laughed a lot at what I said while her sour-faced friend sat there with her long face never cracking a smile. Several years afterwards, she was one of the girls that allowed me to snuggle up close to her under a desk and look down her dress and even touch her developing breasts. Naturally, she also allowed me to kiss her and for a while she was the yardstick by which I judged other girls. |

| |

|

| |

|

Click on the collage to see a vintage advertisement for Knight's Castile soap |

| |

| Maureen, sadly, was another class member that was often absent from school. At that time, girls did not run much and did not play games of exertion, so I never knew if she suffered with shortness of breath like James. She was always very pale but this suited her. I remember on one occasion, for once, I found her alone in the playground. The hag was not with her and this was a rarity. Maureen looked worried, which upset me. Maureen took hold of my hand, a bold move in an open playground, and led me into a quiet and deserted corner. Once there, she turned and showed me her handkerchief. There were spots of dried blood on it. She looked at me with a tragically sad look in her eyes. I am sure that she wanted me to explain why the blood was on her handkerchief to her. I have absolutely no memory of what I said, but I am sure I said something. |

| |

|

Click on the collage to see a vintage advertisement for Lux soap |

| |

I have often wondered whatever happened to Maureen. I always hoped that she found happiness and that she did not suffer illness. I also wondered about the Hag too. I feel sure that she enjoyed a happy and fruitful life.

Although Maureen was pale, she was not as pale as James. His was a deep pale. In retrospect, he looked constantly drained, as if his energy had been sapped from him. He had a poor appetite and would often be scolded by the dinner ladies who roamed the dinner hall while we ate, as he was never able to eat everything on his plate. Although the dinner ladies were probably fine women, they were seen as monsters by most of the kids. In those days, school lunches cost two shillings and sixpence per week. Each day, we would receive a cooked lunch, which was both nutritious and balanced and consisted of meat and two veg. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

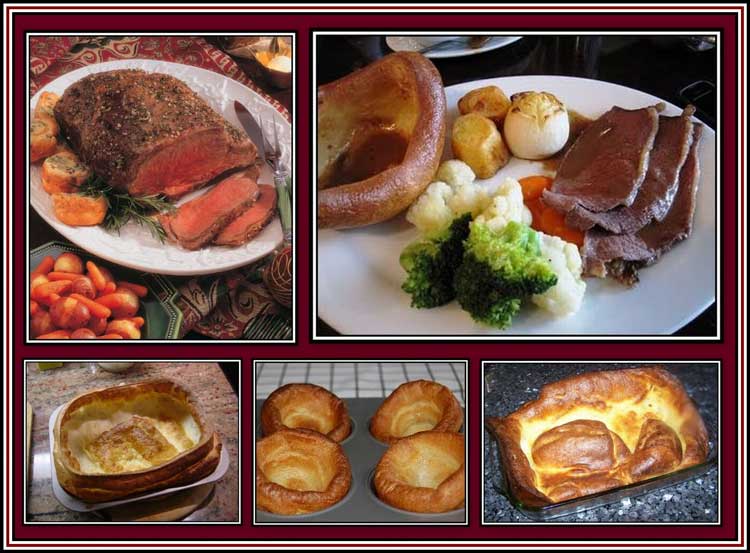

School Dinners |

| |

The meat was generally tasty and not leathery but edible. On a few occasions, I do recall rabbit being served. In those days, rabbit was considered acceptable as an occasional meat. However, I never liked it. The colour of cooked rabbit meat was enough to put me off eating it. Whenever roast beef was served, one of the dinner ladies would walk around the tables dispensing mint sauce to those that requested it. I don’t recall Yorkshire Pudding ever being served with roast beef. |

| |

|

| |

|

Roast Beef & Yorkshire Pudding |

| |

The first vegetable was potato and was not unpleasant. The potatoes were often as not boiled or mashed, or smashed, as they used to be called. Small potatoes were boiled in the true English fashion whenever we had salad and a few chips always accompanied fish whenever it was served. The mashed potatoes were made from real potatoes and not from freeze-dried mush. Earlier that morning, the cook’s helpers peeled the potatoes by hand and once boiled were smashed and then creamed with real butter and milk. Salt had also been liberally added at various times throughout the preparation.

|

|

| The Grand & Glorious Potato - old, new, boiled, roasted, chipped & smashed |

| |

| The other vegetable was generally chosen from carrots, onions, peas or cabbage and was subject to the season. Close to Christmas, Brussels sprouts were often served, much to the horror of most of us kids. However as mushy as the sprouts were at times, they were far from being the most hated and dreaded of vegetables that would occasionally find their way onto our plates and cause our hearts to sink. I am, of course, talking about the turnip and other members of its family. Turnips, parsnips and swedes not only look dreadful, thanks perhaps to their unappetizing colour, but tasted awful too. If anything could possibly be worse than stewed turnip, parsnip or swede, perhaps spring greens and the monstrous, hideous, awful tasting marrow could claim that fame. |

| |

|

| Basic vegetables: Tolerated when served |

| |

|

Disliked Vegetables: Swedes, Parsnips, Turnips & Spring Greens

Eaten only when forced |

|

| Marrows were much loved by gardeners and those that kept allotments, but hated by just about every kid in Britain in the years just after the war. I later learned that villages all of Britain had yearly competitions for the largest marrow produced and prizes were given to the growers. I still shudder at the thought of seeing that creamy coloured slab of vegetable on my plate. I believe that the centre or pulp of the foul vegetable was scooped out and stuffed with minced or ground beef that was only lightly seasoned with ground black pepper. As a result, the whole meat-vegetable mix was horrible in taste. |

| |

|

| |

| The spring green was also a hated vegetable. As a child, I believed that no such vegetable actually existed and thought it really as being the discarded leaves chopped away from a cabbage or from the stalk of the Brussels sprout plant. The colour of these leaves made them look highly unappetizing. I found their texture to be gritty, but this might be unfair since I fear that my initial dislike of this vegetable came from the time that my grandmother cooked it (see To Grandmother's House We Go). Again with a shudder, I recall that a ghastly meal that she cooked or rather murdered when she came to stay with my parents and me. I still believe that she tookthe rotting outer leaves of a discarded cabbage and served their shredded boiled-to-death remains with the dead carcass of some poor creature recently mown down by a steamroller. I remember that her vegetable had the same colour as spring greens and tasted gritty. I suspect that the grittiness of the greens came from their poor preparation and that had she bothered to wash the leaves with a little more diligence, they might have been less loathsome to the taste.

Following the entrée, we were served a pudding, as all deserts were called in those days. Now this was where seconds and thirds were gratefully accepted should they be offered. The pudding was once an English delicacy. All kinds were offered: roly-poly, steamed, and so on and all served with a creamy custard. Custard is not easy to cook and requires patience and constant stirring to avoid the formation of lumps and to stop it from burning. There were no lumps in our school custard and it never tasted burnt! As tasty as all of these puddings were, my favourite without question was the chocolate pudding served with a chocolate custard. My mouth still waters at the thought of such a dessert. The pudding was of a dark brown colour while the custard was of a lighter shade. The pudding and custard complemented each other perfectly. These deserts were true rib sticking farye. Just the kind of stuff young boys liked. |

| |

|

School Puddings - REALLY ENJOYED: Upper Row, Chocolate Pudding, Roly Poly & Apple Roly Poly

Bottom Row, Spotted Dick and Custard |

| |

|

School Puddings - REALLY DISLIKED: Semolina, Rice Pudding & Tapioca |

| |

|

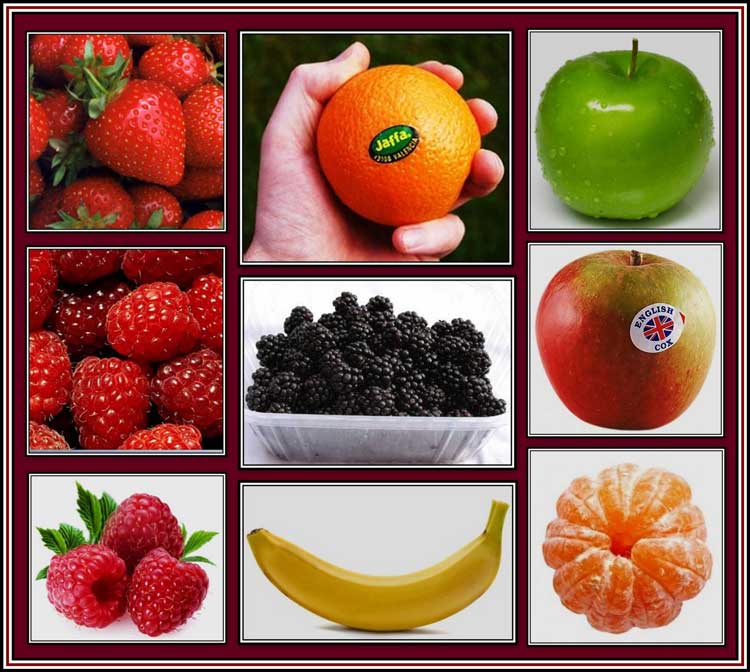

School Puddings - MOST TOLERATED: Various Fruits offered at Lunch |

| |

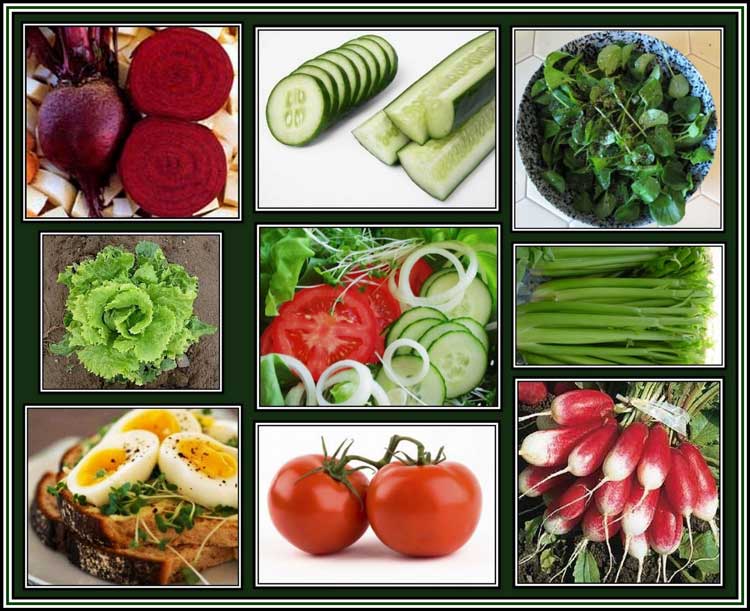

Fridays could be tricky when it came to school dinners, for Friday was the day when the dreaded salad was served. In those days, vegetables and fruits were seasonal. Berries were eaten in summer. Cabbages and root vegetables were eaten in the winter months. Spring and early summer meant new potatoes, tomatoes, cucumber, spring onions, celery, radish and, worst of all, the lettuce. Adults never seem to learn that cabbage, possibly Brussels Sprouts, but definitely lettuce and celery are not to children’s taste. I dare to suggest that they lack the necessary taste buds that would allow them to experience the pleasure of eating them. I feel sure that many adults today would willingly eat more vegetables and salad ingredients had their parents waited until their taste buds had matured and they had developed a taste for them.

The English make a meal of salad. When I was a kid, salad as a meal was perhaps at its height of fame. Victorians, Edwardians and seemingly early Windsorians would serve a salad for the most hated meal of the week, Sunday Tea. This meal was served with bread and butter. What a totally miserable combination of foods. On a plate would be placed a slice of cooked meat: either ham or some other hateful meat. This would be garnished with a sliced tomato, unless you went to my grandmother’s house. Here, she would throw onto the plate a small, mercifully, on the verge of rotting tomato together with a doorstop sized piece of cucumber and a spring onion. Again I shudder! And to add insult to injury, one would have to eat all of this mixture or there will be no cake for you! At my grandmother’s house, as I have said elsewhere, I was always willing to forgo any cake that she might present since it was generally old and stale, but in order to avoid my grandmother’s criticism of my mother and me, I would force her cooking down and thank her kindly for her rotten cake. |

| |

|

| |

Although school salads were nowhere near as foul as those of my grandmother’s they were nonetheless horrible, but had to be endured and eaten. At times, the salad was served with a few chips – a very few chips, but chips nonetheless! We found that wrapping a lettuce leaf around a chip almost made the lettuce palatable and would help us ingest this most disliked of meals. I also hated radish. The taste was too strong, I felt, and to this day, I never ever buy radish, although I am able to consume it when I dine out. Although school salads were nowhere near as foul as those of my grandmother’s they were nonetheless horrible, but had to be endured and eaten. At times, the salad was served with a few chips – a very few chips, but chips nonetheless! We found that wrapping a lettuce leaf around a chip almost made the lettuce palatable and would help us ingest this most disliked of meals. I also hated radish. The taste was too strong, I felt, and to this day, I never ever buy radish, although I am able to consume it when I dine out.

Another of my great dislikes as a child was the new potato. Spring meant the end of whites and King Edwards, some of the potatoes of winter. These were true potatoes. They could be boiled, smashed, roasted and chipped! I defy anyone, anywhere in this world, except for the Irish, to produce a better potato than one that has been roasted a l’Anglaise. Sunday lunch would be the time when the roasted potato would come into its own. The potato, peeled and lightly boiled, would sit around a roast of beef or pork or chicken and then put into the own. After a short time, the potatoes turned golden brown and then perhaps were allowed to continue cooking until they became a darker shade. Such a roasted potato would be crisp on the outside and soft and creamy on the inside. It is the perfect complement to a fine roast of meat served with its delicious gravy together and Yorkshire Pudding.

We saw New Potatoes as a boring vegetable. They could only be boiled. They do not roast well and they cannot be used to make a chip. So what interest were they to a child? Naturally, I enjoy these potatoes today. As soon as they appear in the supermarket or at a Farmer’s Market, I buy them and happily eat them in a variety of ways that I have since learned. As a child, we hated the fact that they were cooked in their jackets! We used to go to great pains to peel the potato before allowing it to enter our mouths. Jacket Potatoes, for we children, were old potatoes that were scrubbed and then pricked with a fork and then baked in a hot oven without being peeled. Once baked, the potato was then sliced open and the cooked potato creamed with butter and left inside the baked skin. Sour cream, cream and shallots or chives were next mixed into the mélange and a little salt and pepper added to taste. Now that is a good Jacket Potato! We saw New Potatoes as a boring vegetable. They could only be boiled. They do not roast well and they cannot be used to make a chip. So what interest were they to a child? Naturally, I enjoy these potatoes today. As soon as they appear in the supermarket or at a Farmer’s Market, I buy them and happily eat them in a variety of ways that I have since learned. As a child, we hated the fact that they were cooked in their jackets! We used to go to great pains to peel the potato before allowing it to enter our mouths. Jacket Potatoes, for we children, were old potatoes that were scrubbed and then pricked with a fork and then baked in a hot oven without being peeled. Once baked, the potato was then sliced open and the cooked potato creamed with butter and left inside the baked skin. Sour cream, cream and shallots or chives were next mixed into the mélange and a little salt and pepper added to taste. Now that is a good Jacket Potato!

|

| |

|

| |

In those days of School Dinners, we drank water from plastic beakers. We were obviously not to be trusted with glasses and probably quite rightly so. Other drinks were not offered: no Coca Cola, no Pepsi Cola or a facsimile were known in schools at that time. It wasn’t until I was about fifteen years old when we were allowed to buy an orange fizzy drink at school. One of the teachers opened a Tuck Shop and employed a few of the senior girls to sell such drinks and a few cakes to those wishing to supplement their lunches. This obviously was the thin end of the wedge and has been a part of the demise of well-balanced-cooked-on-the-spot-from-scratch school lunch and its substitute with carbohydrate-loaded matter guaranteed to pack on the pounds of today’s youth.

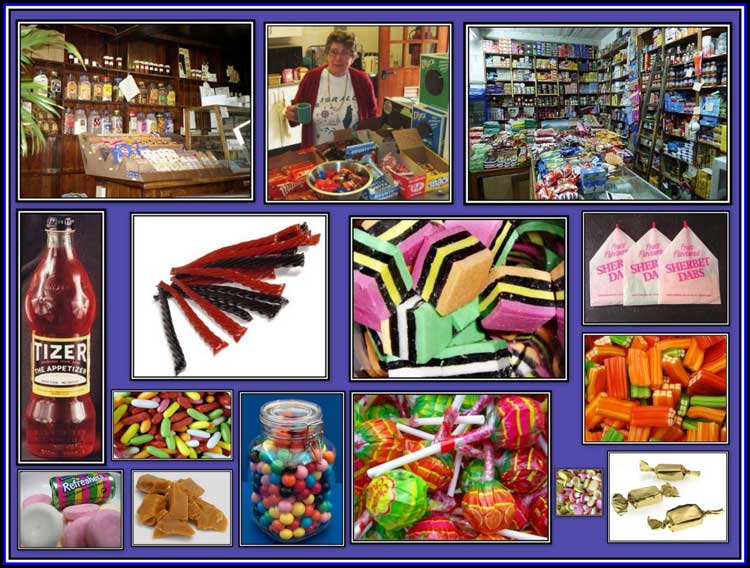

Speaking of fizzy drinks or carbonated water, the best fizzy drink that I have ever tasted was Tizer. Everyone of my age remembers Tizer with great affection. It had a wonderful taste and had a unique colour. It was sold in all those tiny sweet shops that used to exist close to schools. These were wonderful shops if somewhat gloomy and generally run by miserable proprietors who appeared to dislike children. Here the discerning customer could purchase an assortment of cheap, but delicious sweets, which often turned the tongue imaginative colours and stuck to the roof of your mouth. These shops also sold cigarettes and many sold single cigarettes. Many of the shop owners were not too choosey who they sold cigarettes to, I am glad to say. Although Tizer was sold by the bottle, it was also sold in such shops by the glass. The drink was poured into small glasses and served cold and sold for either a penny or two pence a time. Most shops limited the number of glasses that could be purchased by a customer to one. Occasionally on slack days, one might be allowed to purchase a second glass, but this was rare. I really wonder now how well the glasses were cleaned between clients! |

| |

|

| |

F.W. Woolworths also sold Tizer. Here it was sold by the bottle and one drank it through a straw, which I always found to be a delight. I remember going to the Woolworths that once stood on the corner of Garner’s Corner, which was the junction of Whitechapel High Street, Commercial Road, Commercial Street and Leman Street where the Boroughs of Stepney and Shoreditch meet, and sharing a bottle of Tizer with a friend of mine. He was an especially large child. His size came from the fact that he ate and drank great quantities, far more than me. We asked for two straws with the drink and I remember us both drinking the drink as fast as we could while he squeezed my straw so as to impede the flow through it. By doing this my friend hoped to gain the majority of drink for himself. Once I realized what he was doing, I began to squeeze his straw in the hope of getting some of the drink! |

| |

|

| |

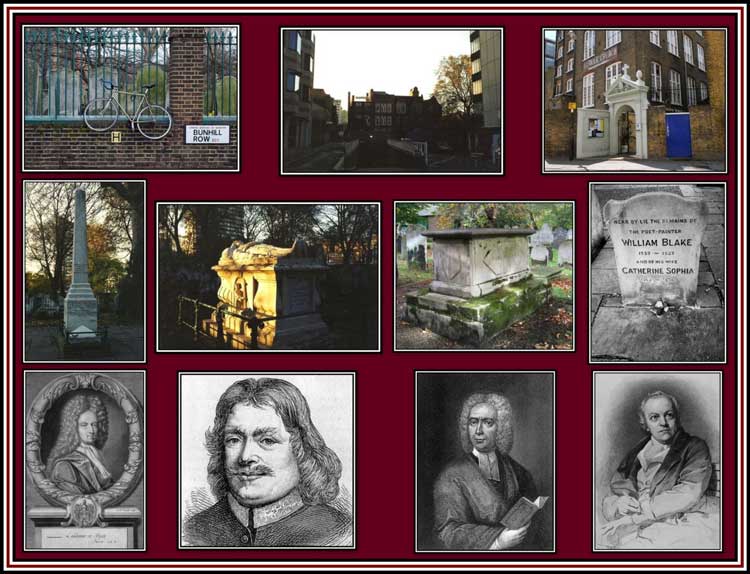

| When I was about eleven years old, I left Sir John Cass Foundation School in the City of London and went to a Technical School in Islington, the Northampton Secondary Technical School. The school was just off Bunhill Row, which is where John Milton wrote Paradise Lost. I remember that across from the school was the cemetery where Daniel Defoe and Isaac Watts are buried. At that time the cemetery was in a poor state. However, since I went to the school, the cemetery has been cleaned up and there is now a path to Daniel Defoe’s grave. |

|

|

Bunhill Row & the former Northampton Secondary Technical School

Middle Row: The Grave stones of Daniel Defoe, John Bunyan, Issac Watts & William Blake

Bottom Row: Portraits of Daniel Defoe, John Bunyan, Issac Watts & William Blake |

| |

The school was wonderful. However, it was not wonderful from an academic point of view, but because the staff treated us as adults. It was an all-boys school, which sounds awful, but this was far from the case. The Headmaster was an ex-RAF flyer and ran the school with few rules. The lack of rules made us feel remarkably free and since we were treated like adults, we behaved like adults. For example, during assembly, we were not required to stand in rows according to our class. Rather we came in and stood where we chose. We listened to the notices, sang a hymn and pretended to close our eyes during prayers. At the end of the assembly, we just left the main hall. There was none of this silly filing out according to your class. We were allowed to talk in the corridors, and as a result, we did not run about the place and we did not yell and shout. The older boys were considerate of the younger ones and I do not recall any bullying or fighting other than minor disagreements between we younger set.

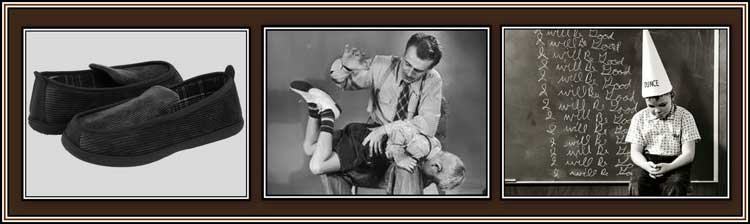

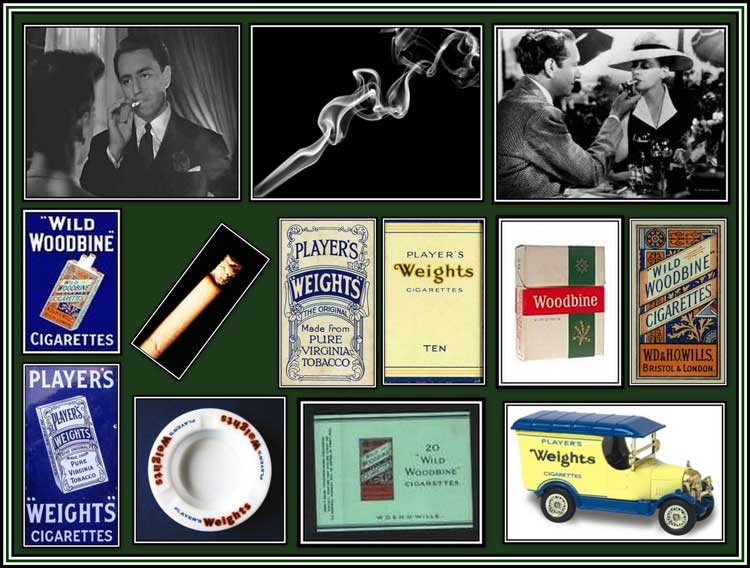

What made the school special to me was that we had to go to another school for lunch. This school was about a mile away and kids in their first year and second years had to be accompanied there by a teacher. But after eating, all of us, including the youngest, were allowed to come back to our school on our own without teacher care. This was wonderful, as it meant that we were free to wander through the local market and buy sweets, Tizer and a tuppnee cigarette. The only requirement was that we had to be back in our classroom by 2 P.M. Failure to be sitting at your desk at this time brought swift punishment. Our teacher kept a heavy slipper especially for this purpose. Once this slipper was brought crashing down on one’s tuchas, one was never late, believe me! |

| |

|

| |

Close to the school was a small Tuck Shop run by a miserable old woman who grumbled all of the time. However, she sold single cigarettes to anyone who had tuppence including kids with no questions asked. These cigarettes were either Weights or Woodbines, both working man’s cigarettes. In those days cigarettes were sold with neither silver foil to help maintain their freshness nor with cellophane wrapping. As a result, the cigarettes were dry, which caused them to be much stronger. I remember when I was really small, my father allowed me to have a couple of puffs of his cigarette, a Woodbine. I remember that the smoke burned my mouth. It was awful – really awful. I remember telling my father how I felt. This caused him to laugh and then say that once I got older, I would realize what a great cigarette Woodbine was. When I was in college and smoking, I did not have much money and so could not afford to buy fancy cigarettes. I remember that a friend and I decided to save money and buy some Woodbines. By then they were sold with silver foil and cellophane wrapping. I smoked one and it was not as I remember. It tasted good, but it was only after I removed the foil and allowed the remaining cigarettes to dry that I got the full effect of a Woodbine. My father was right. There was nothing, absolutely nothing like a Woodbine! |

| |

|

|

Anyway, while I went to that school in Islington, for three pennies, one was able to enjoy a cigarette with a glass of Tizer and not be nagged at by adults. Life was good then. Rock ‘n’ Roll was just exploding on the scene and my friends and I used to stand outside the record shops and listen to the early tunes that were revolutionizing the music scene. We also got to meet kids from other schools, but best of all, besides the cigarettes, we got to meet the girls of the area.

We certainly did not suffer from going to an all-boys school in the slightest. I was totally and utterly miserable when London County Council decided to move my parents and me out of the East End of London and send us out to the wilds of Buckinghamshire! Nice as it was to live in a new home, school was never the same again for me. I found myself plunged into a prison-like school where there were endless rules and, as a result, the place was unruly and utterly miserable. Although there was a Tuck Shop close by, the days of the tuppnee cigarette was over. One had to save up and buy packets of ten. I disliked the remainder of my school years as I found them restricting and claustrophobic and could not wait to leave.

Anyway, back to James: I remember after one of the school holidays where we had a week or perhaps two weeks off, upon return I found that he was no longer a member of the class. The seat next to me was empty. Our teacher, Miss Davis, did not mention his absence at all. I assumed that he was ill, as it was not unusual for him to miss a week here and there during a term. I remember going to his house to see where he was. I was surprised when I knocked at his front door to find new people living there who seemed to have no idea who I was looking for. I was concerned. Seemingly James had disappeared. On the following Monday, I asked Miss Davis where James was and was told that he and his family had moved away. This was not uncommon at that time, as much of the East End was or was about to be demolished and the residents were either moved out to new towns, as was the case with my own family a little later or else to another part of London. Miss Davis had no idea where James moved to.

As I sat in that lecture theatre half-listening to the lecturer, I wondered what had become of James and Maureen and the other kids that I remember at Sir John Cass Foundation School. What had they done with their lives I wondered? Were they happy? Had they done the things that they had wanted? A million questions raced through my mind. Since neither James nor Maureen had been especially strong as children, medically speaking that is, I could not but feel a certain concern, but all I could do was hope that nothing bad had happened to them. |

| |

|

| |

Suddenly the lights of the lecture hall had come on causing an interruption to my thoughts. This together with the half-hearted round of applause that was given to the lecturer by my class mates brought me back to reality with a start. All around me my class mates were standing up and making their way out of the hall. They were off home or to the library, perhaps to begin another long night of study. As I walked up one of the side aisles and out into the foyer, my thoughts returned once more to James and Maureen. I had so many questions about them, but had no hope of finding any answers to them. As I went out into the late afternoon air and began to make my way home, I realized that all I could hope was that whatever had become of them that they were surrounded by people that loved them and that they were enjoying good health. |

| |

|

State University of New York at Buffalo School of Medicine |

| |

| |

| EPILOGUE |

| |

As I grew up, like most people, I began to enjoy vegetables and have developed a taste for most. Today, I eagerly eat all kinds and am always happy to try new ones or old ones cooked in a different manner. However despite the development of a taste for most vegetables, there are still some notable exceptions, as some things do not change.

Despite all efforts, I have failed to acquire a taste for the dreaded marrow, parsnip, swede and turnip. When I was a young man and eligible and upwardly mobile, I often found myself invited to dinner parties where one was supposed to meet interesting people. However, more often than not, these affairs proved to be try-outs for would-be chefs who were premiering a new and supposedly delicious Sunday Supplement recipe. Naturally, one was expected to bill and coo and pretend that their effort had been a success. Most of the time, this was too much of a stretch. However I fear that other times I was unable to play the good guest. I have been known to upset many hostesses who had served one or more of the dreaded vegetables and who had insisted that I was going to absolutely going to love what they had done to one of them.

In those days, I was most gracious and agreed to sample the foul looking concoction placed on the table often in an orange Le Creuset dish. I fear that despite the excellence of the table setting and of the cookware used and despite being told that this dish was guaranteed to change my mind about one of the dreaded vegetables forever, I fear that all efforts failed. The sight of a miserable swede or a mashed turnip always brought forth the same sense of revulsion that it had done during lunch at Sir John Cass Foundation School. Tragically for mein host, one look, one sniff proved more than enough for me and I was unable to suppress a shudder. So, should you wish to invite me for dinner, I beg you, please do not serve one of the dreaded vegetables unless you don’t mind my shuddering as I decline when it is offered.

By the way, should the reader be interested, I never saw Rheumatic Fever during my medical career. But then this is not surprising since we live in an age of antibiotic treatment. |

| |

| |

| |

|

RHEUMATIC FEVER: |

| |

In 1953, when I was 10 years old, I was diagnosed with Rheumatic Fever and was confined to bed for five months. I don’t recall having a rash at anytime. During this time I underwent a volume growth spurt, which I have been fighting ever since!

My teacher lived across the road from us and she made sure I always had reading matter on hand and thanks to her I developed a love of reading. Fortunately for me I was not held back at school and managed to stay abreast of the class.

This was a time of few antibiotics for treatment of the illness and I was treated with the sulphur drug, Suphadiazine, which I took on a regular basis until the age of 23.

1953 was a memorable year for me because of two other events: the coronation of Queen Elizabeth and the conquest of Mount Everest. Television was not yet a part of South African life at that time and I remember listening to the coronation and news of Everest on the radio. My family had borrowed a radio from my rich uncle since were too poor to purchase our own. Unfortunately for us, my uncle took back his radio once I was no longer confined to bed.

I can still recall the pain that I felt in my legs when I first got out of bed. My leg muscles were very weak as a result of my remaining in bed for so long. Unfortunately, physiotherapy was not commonplace at that time …… at least not for my family.

From this illness, I have a heart murmur, which I learned was often the case in those that suffered with Rheumatic Fever. This proved to be of some concern a number of years later when I underwent chemotherapy. Fortunately, serial Echocardiograms demonstrated no further damage to the heart valves.

A friend who was also diagnosed with this disorder at about the same time as me sadly was less fortunate and died soon after he was married. I also knew of two others who, as adults, were diagnosed with the disorder. By this time the antibiotic armament had grown, and following appropriate treatment, they quickly returned to a normal life.

From a reader |

| |

| SCHOOL DINNERS |

| |

Once we moved from Port Talbot to Swansea, my sister and I were sent to a very small primary school in a nearby village called Jersey Marine. The school had a kitchen and a cook whose name I believe was Mrs. Madge. She produced the most stunningly good meals from the fresh food that was brought to the school each day. For one shilling and eleven pence a week, we enjoyed lunch each day and left-over cake during the afternoon break.

Peter F. Lane |

| |

What I remember most about school lunch were the strict rules and the smacks which followed should proper etiquette failed to be followed. I disliked the semolina pudding often service up for pudding and I remember choking on a tanner in the Christmas Pud. These coins were far more dangerous than the threepenny bits.

Anthony Bradley |

| |

In Australia, only those who went to private schools (paying) were provided with school dinners. Those of us that went to ordinary schools (free) took their own lunch. In my case, this was usually a sandwich most often of Vegemite. I remember that we were given half a pint of milk each day. It was delivered early each morning and was allowed to sit in the sun for a few hours causing the cream to congeal. I found this drink to be disgusting and gave mine to a friend who seemed to enjoy the foul mix. Luckily for me, no one checked to see if we drank the drink or not. Later I attended a school where baked beans were offered on the menu, which I believe was the cause of my lifelong dislike of this food. I did enjoy eating the sandwich and fruit that I occasionally bought at the school Tuck Shop.

Margaret - Australia |

| |

I was brought up in Clapham, in South London, where I lived with my family. Since one of my grandmothers came from Spain, I was used to foods with lots of spices. I learned to enjoy highly flavoured foods at a young age. Unlike most of my friends, I was used to eating peppers and aubergines and having my food flavoured with garlic. As a result, I absolutely hated School Dinners. I found them to be too bland for my taste and the vegetables to be overcooked. School Dinners are responsible for my dislike of certain foods. I remember the awful liver that was presented to us. It had the consistency of the sole of a shoe and was covered with glutinous gravy and served with overcooked cabbage and much cabbage water. We were also served salads with cold baked beans, which I also found unappetizing. Even worse, and the bain of my life, was lumpy potatoes! I was obviously a fussy child and was unable to tolerate the slightest lump in my mash, as it made me feel sick. Once we were finished eating, we were made to take our plates to a dinner lady who checked our plates and scrapped the remains into a plastic bucket, which I presumed was given to some nearby pigs! Whenever I left more than the dinner lady deemed acceptable, I was sent back to the table with instructions to eat more. As a result, I developed tactics to help me avoid eating more. I would try to hide some of the food under the knife and fork, often causing the cutlery to sit high above a mound of potato or else manage to dump some food on a neighbour’s plate once I had distracted her attention.

I could not wait to get home from school so that I could enjoy a cheese and tomato sandwich, which my mum made for me at tea-time. This is one of my favourite things to eat at this time of day, even now!

Frances Webb-Thurgood |

| |

My mother was an excellent cook. She made wonderful pancakes and delicious apple pies and many of friends would enjoy coming to our house in the hope of tasting them. My mother was an excellent cook. She made wonderful pancakes and delicious apple pies and many of friends would enjoy coming to our house in the hope of tasting them.

School dinners were a necessity for me since both my parents worked. My father was a cabinet maker and my mother, a tailoress. Believe it or not, I used to enjoy school dinners. I don’t recall how much they cost – probably about one and six.

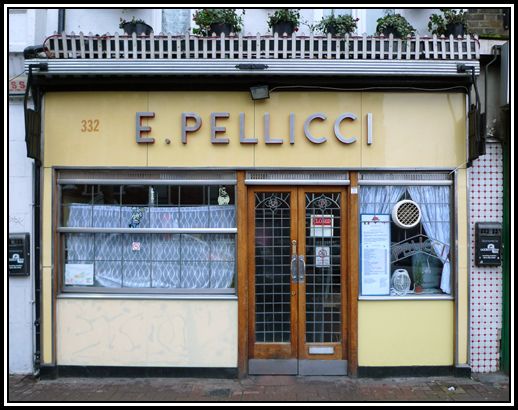

One lunchtime, or as we used to call it, dinnertime, a friend asked me go up the caf’. At the time, I was used to eating my school dinner and then spending the rest of the time in the playground. To me Caf’s were places were adults went – kids of our age did not go to caf’s! My friend said that we could get egg ‘n’ chips, beans and a slice of bread and a cup of tea for the same price as we paid for our school lunch. In addition, we would be going where the boys went, and by the boys, he meant the local villains, characters such as the Kray Twins.

This was my introduction to Pellicci’s on the Bethnal Green Road and to my friendship with Nevio, the son of the owner of the caf’. I did not tell my parents that I was now using my dinner money to spend in Pellicci’s. Some years later, my father found out when he became friendly with Nevio when they played darts together in various pubs in the area.

Peter Thurgood |

| |

To be honest, I cannot remember much about school dinners. I do remember often using my dinner money to eat at Pellicci’s Café on the Bethnal Green Road. It offered great food and the company was always interesting. I am told that the Kray Twins ate there. I don’t know how true this is as I never saw them there.

John Arno |

| |

When I was at secondary school, there was a policy that did not allow those that lived close by to stay for school dinners. Those that did stay for lunch came from the surrounding villages and small towns. Since packed lunches were unheard of at the time, I had to go home for lunch. Since our school did not have any facilities to produce meals, those who wanted a school dinner had to go to a local primary school.

I did eat at school when I was in primary school. This school also lacked a kitchen but had a preparation area. Meals were brought in each day in huge metal containers and arrived by lorry during the morning hours. We used to see them through the classroom windows. We ate our lunch on collapsible tables and sat on small benches. There were 10 kids to a table – four each side and one at each end. I seem to remember that the one at the end of a table was the table monitor and was responsible for collecting up the plates at the end of the meal. I cannot remember if we had to line up at a serving hatch for our food or if plates of foods were brought to us. I also can’t recall much of the food except for the custard. Having been stored in a metal drum gave the custard a taste of its own! I cannot say that it was unpleasant, just different. Two members of staff sat at a table set on a stage. From here they could see us all and direct operations. I realize now that doing dinner duty was the short straw, since I did my share of such duty having been a teacher for nearly 40 years.

After lunch we were allowed to leave the school premises – which would not be allowed today. I used to go and visit my grandfather, who lived chose by, and have a cup of tea with him.

Brian Hall |

| |

School lunches? I don’t have much memory of them except for my mother’s sandwiches. These were usually bread and jam. By lunchtime, the butter and the jam had generally soaked into the bread, making the sandwich a soggy mess! I would also be given a piece of cake and either an apple or a banana. At times, I would have money to buy a meat pie or a pasty at the Tuck Shop. Unfortunately it did not sell hot fatty chips!

Ian Williams. |

| |

I used to like some things offered at dinner time. My favourites were Shepherd’s Pie, especially the crisp crust and Bangers ‘n’ Mash. I loved the often burned sausages. I hated Rice Pudding and that horrible scoop of jam that was served with it. Try as I might, I was never able to keep the rice and the jam separated and the dessert would turn into this pinky-muddy-hateful mass of tasteless muck, which I was forced to eat! I still shudder at the thought!

A reader. |

| |

Back

to Part two - The Film

Copyrightę

2010 -

: Charles S. P. Jenkins |

|