THE GRANADA THEATRE CIRCUIT

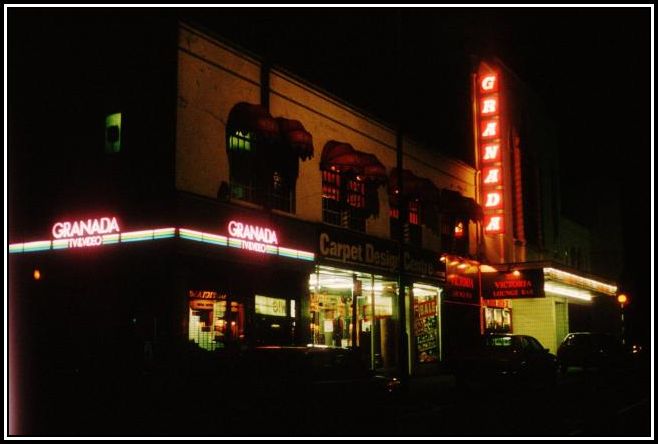

The Granada Theatre Walthamstow, currently the EMD

The Granada Theatre Walthamstow, currently the EMD

——oooOOOooo——

PART THREE: THE RISE & THE GLORY DAYS

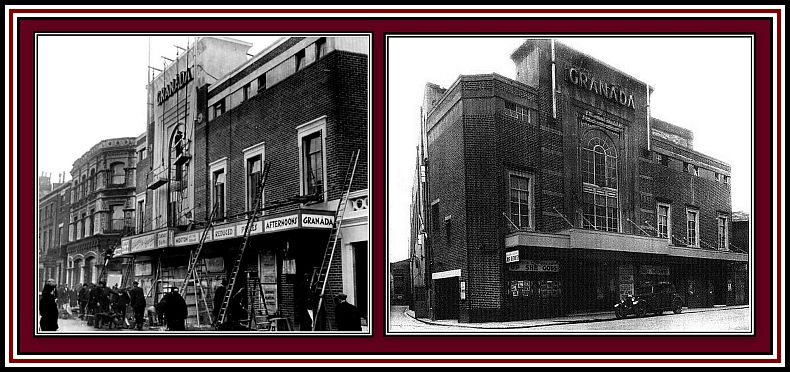

The Granada Dover

Left: during construction in 1930; Right: soon after opening

Most Granada Theatres were unlike any other cinemas in Britain. Their uniqueness was the result of their distinctive architectural style and decor. Each theatre had an exotic quality. The décor of the foyer and auditorium, and oftentimes the specially built waiting areas, were such as to give the impression of entering a palace or a cathedral from another era. Granada Theatres were rare, but one found and once seen were not forgotten.

As I said, sadly there was no Granada Theatre any where close to where I lived in London. I believe that the nearest Granadas were in East Ham and Walthamstow, but in those days, one did not travel far to go to the pictures, and so I did not visit one until I moved from London. Unfortunately, the circuit had evidently never found suitable to build theatres in most of the East End and Central London.

The four largest and possibly grandest of all Granada Theatres in the Circuit were in London. Each had Cecil Massey as architect and Theodore Komisarjevsky as designer of the interior. These were in decreasing size, the Granada Tooting, the Granada Woolwich, the Granada Clapham and the Granada East Ham. Both Ceil Massey and Theodore Komisarjevsky worked extensively for the Granada Theatre Circuit and help build new theatres and convert other cinemas purchased by Sidney Bernstein for his circuit. The first full project that Ceil Massey and Theodore Komisarjevsky worked on was the Granada Dover, which opened on 8th January, 1930. Evidently this theatre did not suit Mr. Bernstein for it was sold to the ABC Circuit in June 1935.

The Granada Theatre Clapham Junction

The Granada Theatre Clapham Junction

(Left): as it was; & (Right), as it is now (Transformation House & Lumiere Apartments)

The Granada-Gala East Ham

The Granada-Gala East Ham

(Left) Exterior ; (Right) Interior

The films screened on the Granada Circuit were varied. Many showed the films also shown by J. Arthur Rank’s Gaumont Chain in areas where the chain was not represented. However, at the time I became aware of the theatres, Mr. Bernstein had recently entered into an agreement with 20th Century Fox to replace the J. Arthur Rank Circuits to screen their films. This occurred at the time when 20th Century Fox was about to release their spectacles produced in their new widescreen process, CinemaScope. This agreement proved both lucrative and prestigious for the Granada Circuit.

How was Mr. Bernstein able to enter into an agreement with 20th Century Fox so obtain the rights to screen the company’s films by the Granada Circuit?

In the early 1950s, the price of a television set began to fall and became within the reach of the average cinema going public. This sent shivers down the collective spine of movie moguls throughout the world, but especially in Hollywood, as they knew that this would bring a reduction in cinema ticket sales. However, Hollywood did not lie down and die as television’s popularity grew, but decided to combat television with something that they believed could not be got at for . The moguls decided on both spectacle and gimmicks to attract their dwindling audience back to the cinema.

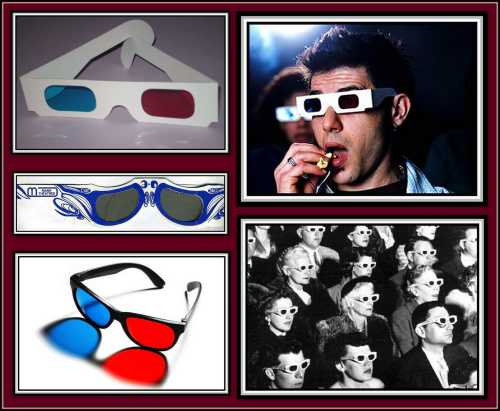

One such gimmick, first introduced in 1952, was films made in 3-Dimension or 3-D. Here the film image was such as to give the illusion of enhanced depth perception, which is to say that the images stood out from the screen. This effect was seen or achieved by the use of special (polarised) glasses, which had to be purchased along with a ticket of entry.

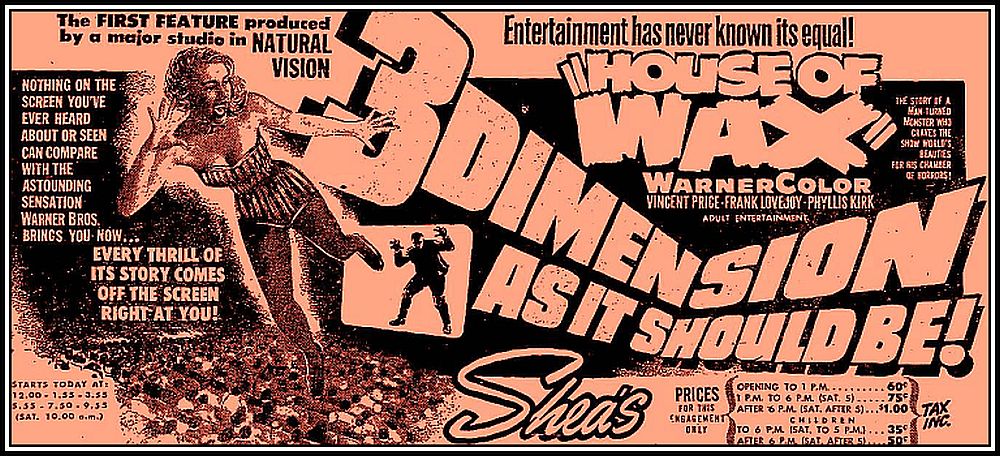

Although a gimmick, a number of films were produced in this process with well known film stars and with a reasonable storyline. Perhaps the most successful at the box office were Hondo with John Wayne, the musical, Kiss Me Kate and the classic horror film, House of Wax, which was given an H certificate in Britain.

3-D was used to spectacular effect in each film. In Hondo, flaming arrows and lances flew out of the screen while marauding Indians rode their horses at the audience and seemed to leap over the screen at the last minute. Impressive stuff! Kiss Me Kate, on the other hand, used 3-D in a less spectacular manner and only sent a few pots and pans and a banana in the direction of the viewer. However, House of Wax used 3-D in a spectacular fashion including a scene where a barker-cum-doorman slapped a ball attached to a bat out into the audience and another where a raging inferno filled the screen and flaming beams and melting wax figures appeared to fall into the audience.

There were however a large number of films that attempted to be equally as spectacular, but suffered from having a less than credible story, such as Gorilla at Large. These films proved disappointments, especially to this cinema-goer!

I remember seeing Kiss Me Kate at the remarkable Empire Leicester Square and being very impressed and intrigued by the 3-D process. mother, on the other hand, was annoyed by the special effects. mother, having seen the show on the stage, did not understand the need for 3-D, especially since the story, the acting and the music were strong. She also resented having to pay an additional sum of money for glasses that were of no value after seeing the film and found them annoying to wear while trying to enjoy it. I was not surprised to learn that others had similar feelings of discontent with 3-D!

It is interesting to note that even Alfred Hitchcock made a film in 3-D, Dail M for Murder. By the time the film was ready for release, the popularity of the process was on the wain and so the studio decided to release it in normal format.

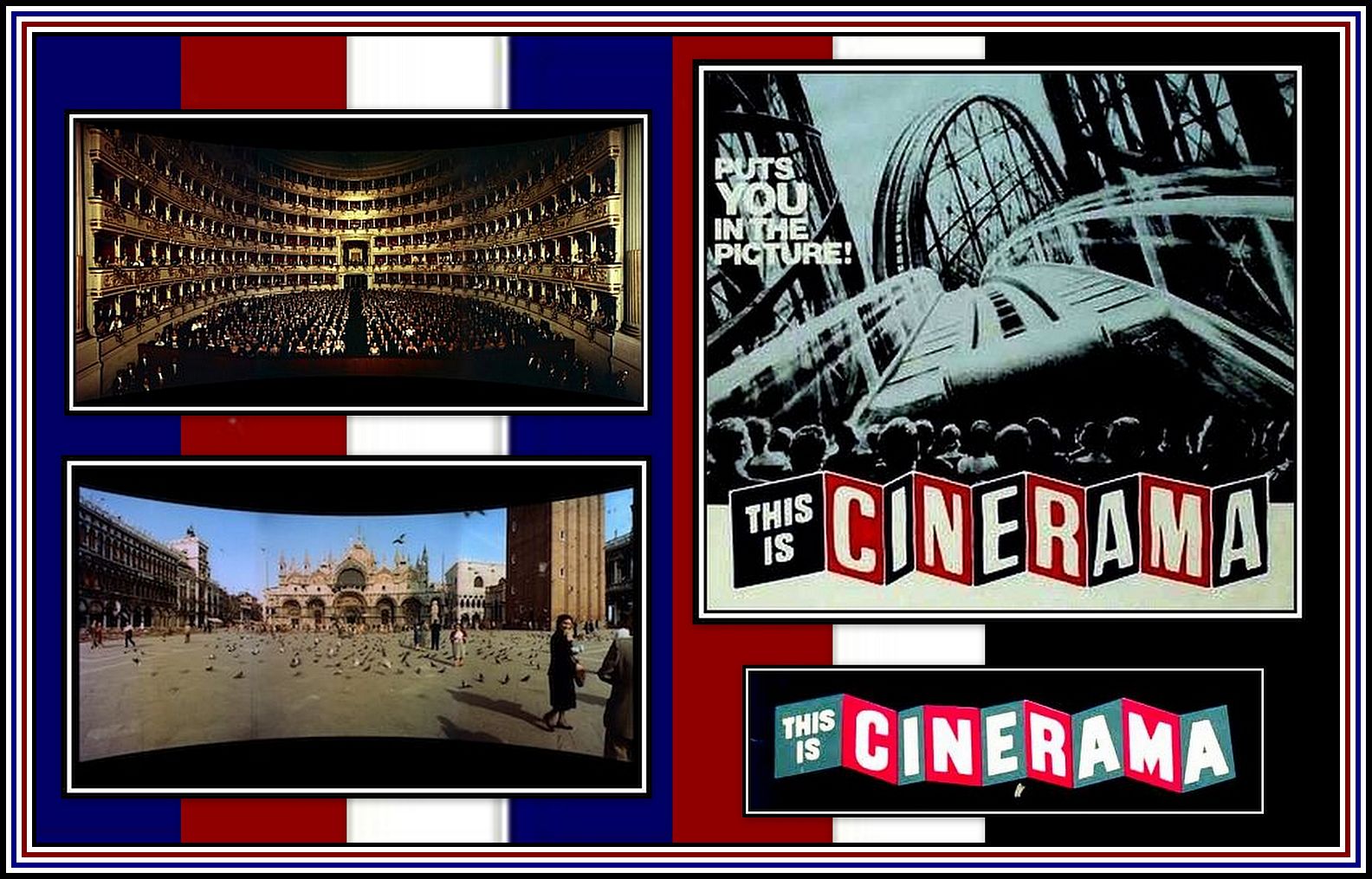

Despite the monetary success of 3-D, Hollywood was soon on the look-out for other gimmicks that would not need the use of special glasses. Cinerama had developed a process whereby the illusion of depth was achieved. However, this process required three special screens and three projection devices for viewing. These requirements limited the number of cinemas where films made in this process could be shown.

This is Cinerama

This is Cinerama

Top Right: Poster for first film produced in Cinerama; Bottom Right: Cinerama logo

Scenes from the film showing (Top Left) La Scala, Milan and St. Mark’s Square, Venice (Bottom Left)

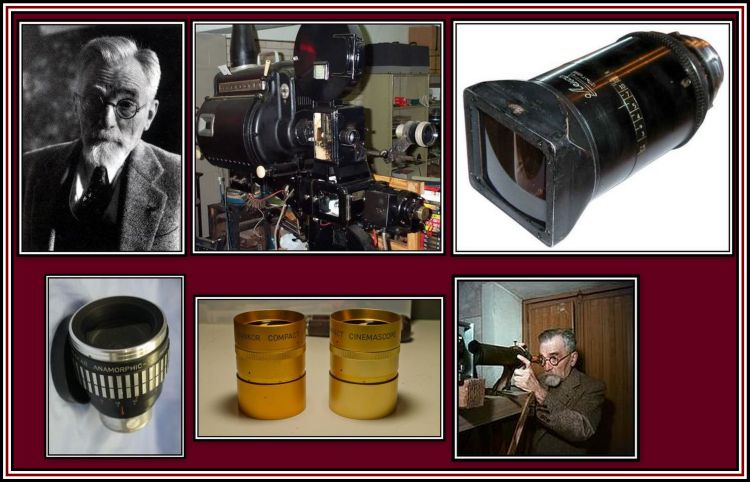

20th Century Fox in their search for something special was fortunate when Spyros Skouras, the then head of the studio, remembered the work of Henri Chretien. Monsieur or rather Monsieur le Professeur Chretien developed and patented a film process that he named Anamorphoscope in 1926.

Henri Chretien avec ses lentilles photographiques célèbres

Henri Chretien avec ses lentilles photographiques célèbres

For a number of years Monsieur Chretien could not interest anyone in his process. However, it was to form the basis of what was to be known as CinemaScope, which was an anamorphic lens series used for shooting films in widescreen format and which was advertised as The Dimensional Photographic Miracle You See Without (the aid of special) Glasses. What CinemaScope allowed was the illusion of depth without the need of wearing polarised glasses. The process was based on lenses that employed an optical trick, which produced an image twice as wide as that produced with conventional lenses. The image was compressed onto film when shot and dilated laterally when projected onto a screen.

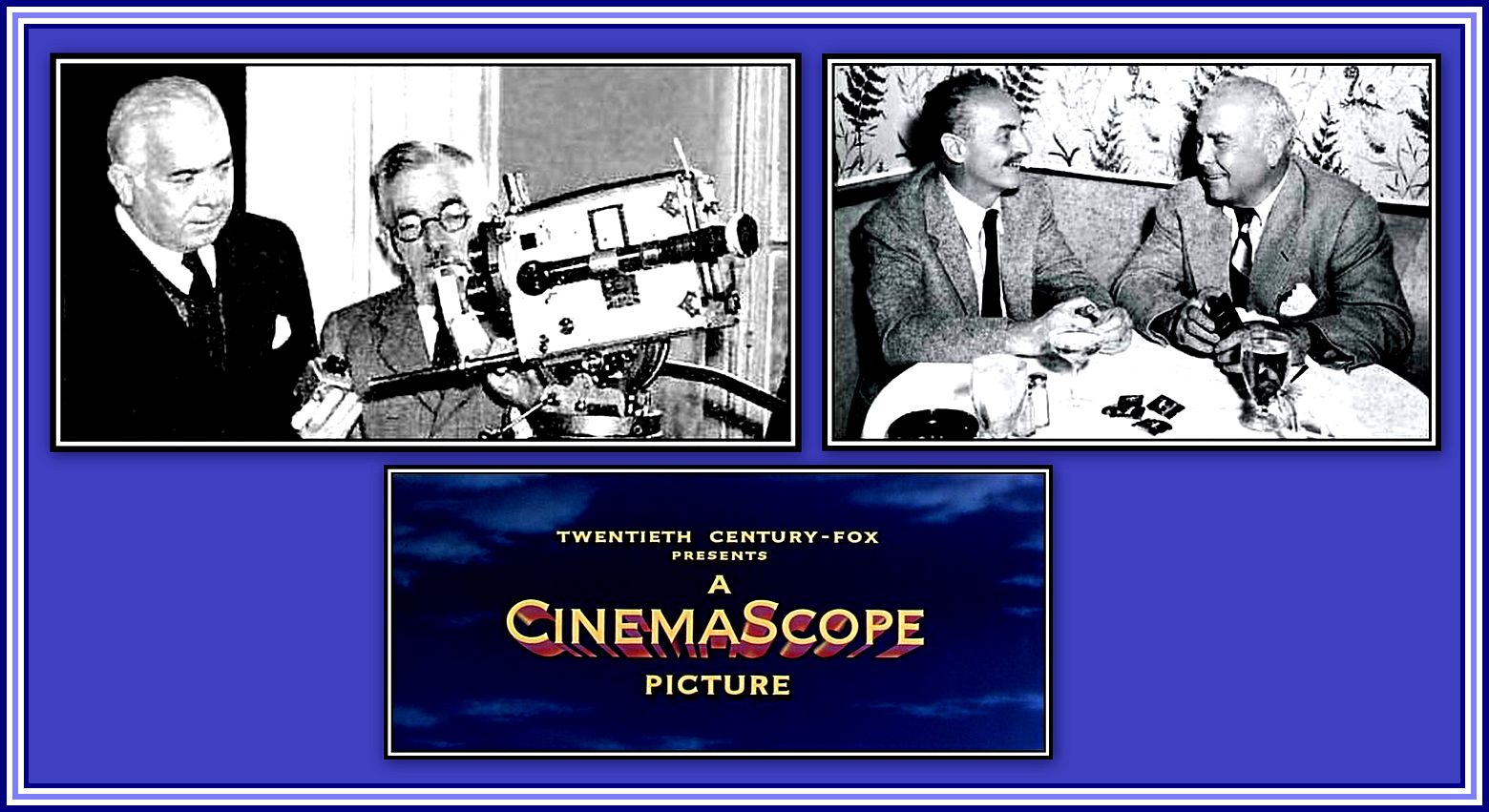

Spyros Skouras with (Top Left) Henri Chretien & with (Top Right) Darryl F. Zannuck

Spyros Skouras with (Top Left) Henri Chretien & with (Top Right) Darryl F. Zannuck

Spyros Skouras rushed to France to secure the lease rights of Monsieur Chretien’s anamorphic lenses. Once 20th Century Fox had the lenses, the company set about promoting its product and using them in the filming of a number of spectacles, the first of which was The Robe. The Robe was based on the 1942 novel of the same name by Lloyd C. Douglas and starred Richard Burton, Jean Simmons (who had replaced Jean Peters), Victor Mature and Michael Rennie. Although 20th Century Fox’s How to Marry a Millionaire with Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable and Lauren Bacall was completed first, the company decided that The Robe was obviously a classier product and decided to release it first in order to give the CinemaScope product greater credibility.

In 1953, the year that The Robe received its premiere, 20th Century Fox had an agreement with the J. Arthur Rank Company to screen its films in Britain and incidentallyhad a reasonably large stake in the cinema of The Gaumont Circuit. In order for films produced in CinemaScope to be shown in local cinemas, a larger screen and equipment for stereophonic sound had to be installed. In order to accommodate a larger screen, J. Arthur Rank soon realised that this would mean that some of their cinemas would have to lose some seating and the company did not enjoy this thought especially at a time of falling ticket sales. In addition, 20th Century Fox wanted the Rank Company to agree to hold over any Fox release for an additional week or weeks in their cinemas should a film be enjoying success that would warrant it.

Rank and 20th Century Fox came to an agreement over a number of points, but Rank felt that its customers wanted a fresh programme each week in its cinemas and refused to allow hold overs. 20th Century Fox refused to budge on this point and, as a result, Rank and 20th Century Fox got into an argument and must have fallen out.

However, one man’s loss was another man’s gain! As a result of the balking of J. Arthur Rank over the loss of a few rows of seats and not wanting to allow hold overs, 20th Century Fox was forced to look elsewhere for a distributor. At this time, no other distributor operated as many cinemas as J. Arthur Rank with a combined total of 502 Odeons and Gaumonts. The Associated British Cinemas Circuit (ABC) operated 281 cinemas, but whether the company was approached or not to screen their films, I cannot say.

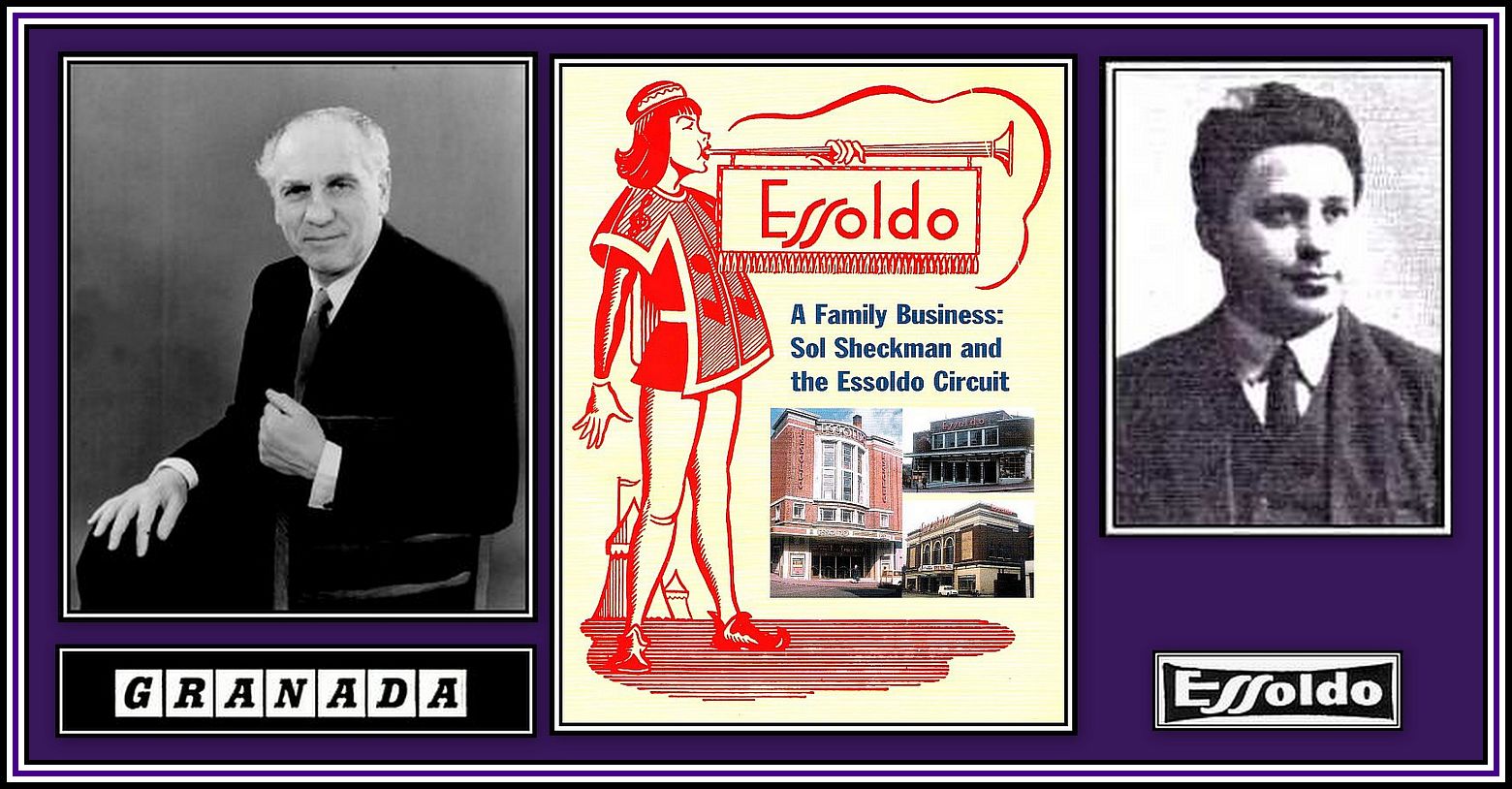

What 20th Century Fox did was to sign agreements with both the Essoldo Circuit with its 183 cinemas and the Granada Circuit with its 56 theatres to screen its films. This newly formed fourth cinema circuit of 259 cinemas allowed 20th Century Fox to have its films seen in all major cities and towns in Britain.

The Essoldo and Granada Circuits proved more than willing to install new wide screens and stereoscopic sound systems into their cinemas. Evidently both Sol Sheckman and Sidney Bernstein were quick to appreciate the advantages of screening first-run films made by 20th Century Fox and produced in CinemaScope in that it would not only give their circuits greater credibility in their business circles, but also keep the box office tills ringing despite some small loss in seating capacity! Carpe diem ……. O Captain! My Captain!

Sidney Bernstein (Left) & Sol Sheckman (Right)

Sidney Bernstein (Left) & Sol Sheckman (Right)

The agreements between The Fox Company and The Essoldo and Granada Circuits essentially brought about a Fourth Cinema Circuit in Britain. However as 20th Century Fox tended to release roughly one major film each month in Britain, The Fourth Circuit did not operate on a full-time basis. During those weeks when Fox releases were not being screened, both The Essoldo and Granada Circuits were able to enter into agreements with other companies to show their releases. I remember that during such times the Essoldo Bethnal Green regularly showed films seen on the ABC Circuit, which included MGM and Warner Brothers films. As a result, although I was able to see The Land of the Pharaohs (where poor Joan Collins gets her’s) and Drumbeat, much to annoyance, I had to travel to Hackney to see The Prodigal (forget CinemaScope and Perspecta Stereophonic Sound, to be honest I went to see Lana!) and The Valley of the Kings, since Fox films regularly replaced conflicting MGM releases.

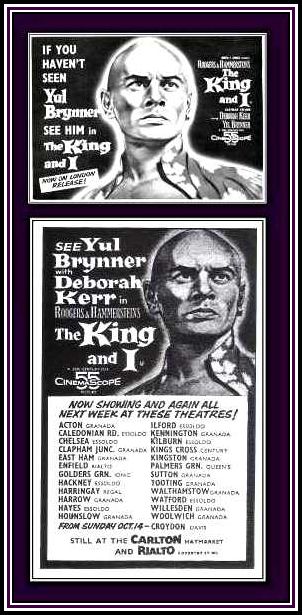

Apparently neither The Granada nor The Essoldo Circuits complained about being required, when necessary, to hold over a film for an additional or additional weeks. I am sure that hold overs must have occurred in certain areas of Britain such as large cities and seaside resorts, I can only remember one Fox film being held over in a suburban circuit cinema and this was The King and I.

And so between The Granada Theatre and The Essoldo Circuits, 20th Century Fox was able to ensure that just about every city and town in Britain had a cinema willing to screen its films.

And so began the glory days of the Granada Circuit when seats were filled and spectacular films were shown on its screens. Those indeed were the days!

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to go to PART FOUR: THE GIANTS THAT MADE GRANADA GREAT

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to return to PART TWO: INTRODUCTION

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to return to THE GRANADA THEATRE CIRCUIT

Home Page

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to return to the TABLE OF CONTENTS

——oooOOOooo——

Charles – Another great article about another grand old London theater! The Granada Tooting’s Gothic interior is certainly spectacular, and nothing like its exterior. The Granada Circuit is a lot like the old Saenger Theatres, which operated thought out the South. Those theaters, like the Granada Tooting, were grand movie palaces, sporting a dazzling array of styles from ancient Egypt to a Venetian palace. There is one in Biloxi, Mississippi. It is now a performing arts center. I’ve performed there numerous times. Again – a great article! Take care, Anthony

The main reason that Rank Odeon circuit fell out with 20th century Fox was that Rank did not mine putting in a wide screen and anamorphic lens on projectors, but Rank did not want the much higher expense of installing stereophonic sound, which involved new speakers and amplifiers, plus a magnetic sound head on projectors. Granada installed the stereo with 3 speakers behind screen ( left cener and right) plus additional speakers around the auditorium walls for effect sounds.

In the cinemas that Rank did install the Cinemascope with stereo they often did not put the effects speakers on the walls.

Many thanks for providing this interesting information.