THE GRANADA THEATRE CIRCUIT

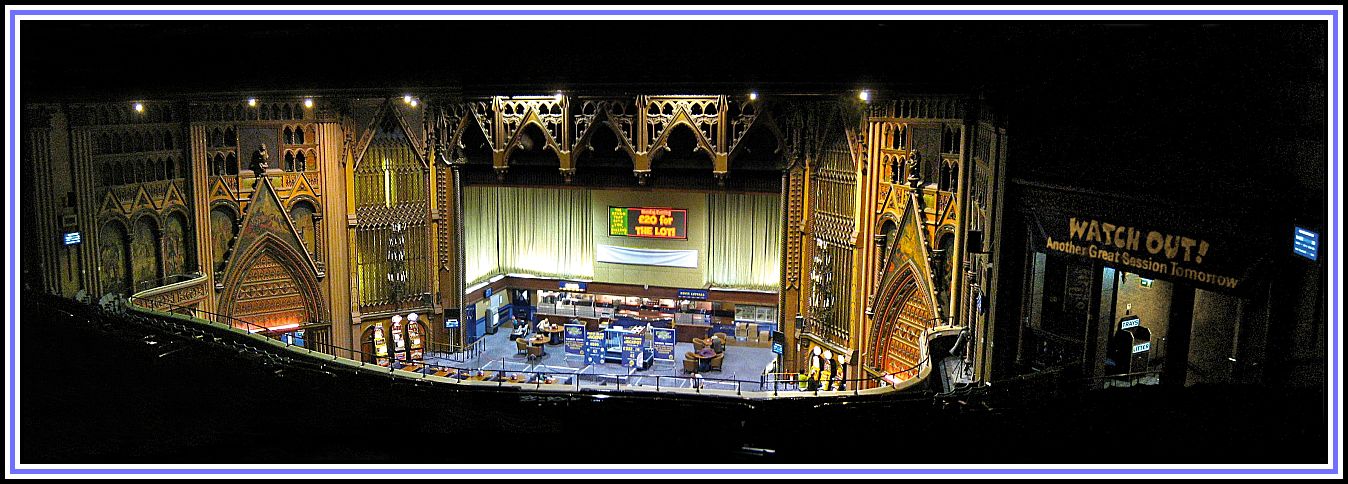

The Proscenium Arch, stage and part of the Auditorium of the Granada Theatre Tooting

The Proscenium Arch, stage and part of the Auditorium of the Granada Theatre Tooting

This panoramic view was produced by Peter Kurton

——oooOOOooo——

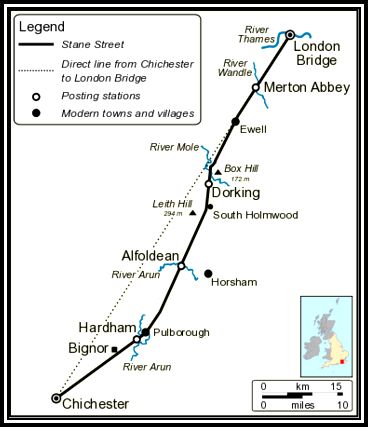

Today Tooting is a busy area of South London in the Borough of Wandsworth, and like other areas of London, it has an interesting history that goes back to Roman times. The Romans constructed a road, Stane Street, soon after their arrival in England that linked London to Chichester (Noviomagus Reginorum) and which passed through an area that was to become Tooting. Tooting High Street is built on the road and London Transport’s Northern Line follows the course of the road through Clapham and Tooting to Colliers Wood and Merton.

Slang Street, running between London & Chichester

Slang Street, running between London & Chichester

By Saxon times, the lands of Tooting and Streatham passed to the Abbey of Chertsey. Tooting, or Totinges, is mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086) and in Norman times the area now passed to the De Gravenel family, giving the area the name of Tooting Graveney, and making them the Lords of the Manor.

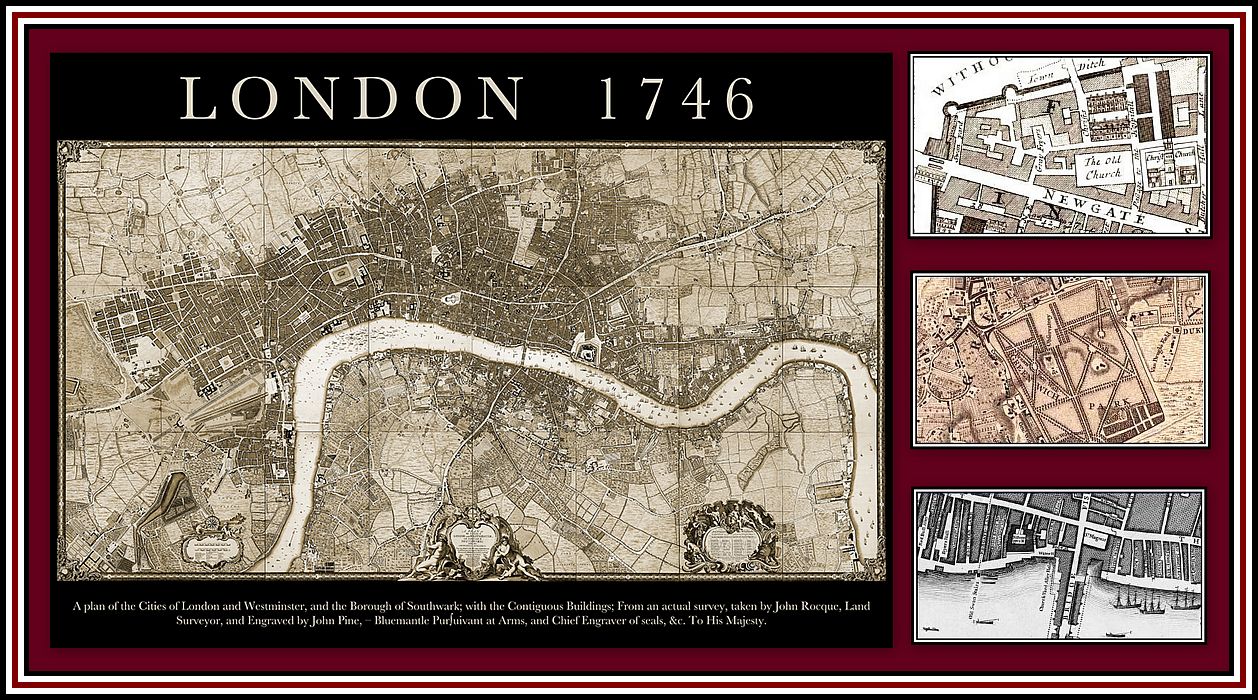

By the 18th Century, the De Graveney lands were acquired by the City of London merchant Joseph Salvador, who built Salvador House here as his family’s country home in 1744. The estate is shown on John Rocque’sMap of London, first published in 1746.

A Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster,

A Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster,

and the Borough of Southwark with Continguous Buildings, 1746

John Rocque was a land surveyor and cartographer; Engraving by John Pine

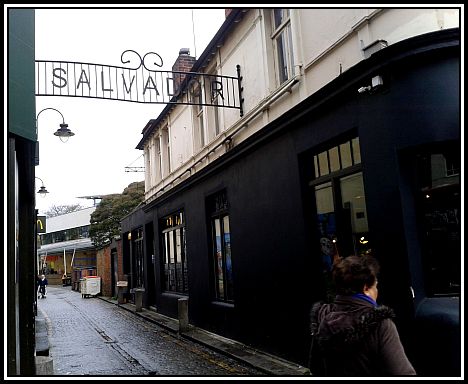

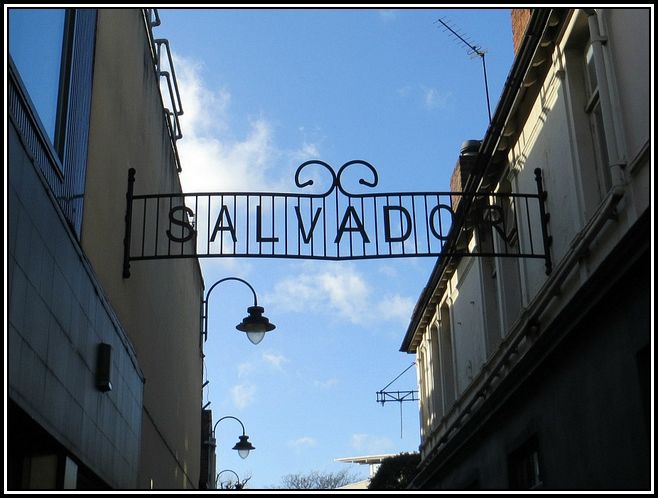

If one looks at the map of Tooting today, one can find a small alley way or Passage as the Borough of Wandsworth likes to call it, named Salvador. It is found just off the Mitcham Road and within a few minutes walking distance of Tooting Broadway Underground Station with the erstwhile Granada Theatre a few steps further along the road. The name of the passageway is all that is left to remind us that once this area was part of the Salvador Estate and where the country home of Joseph Salvador once stood.

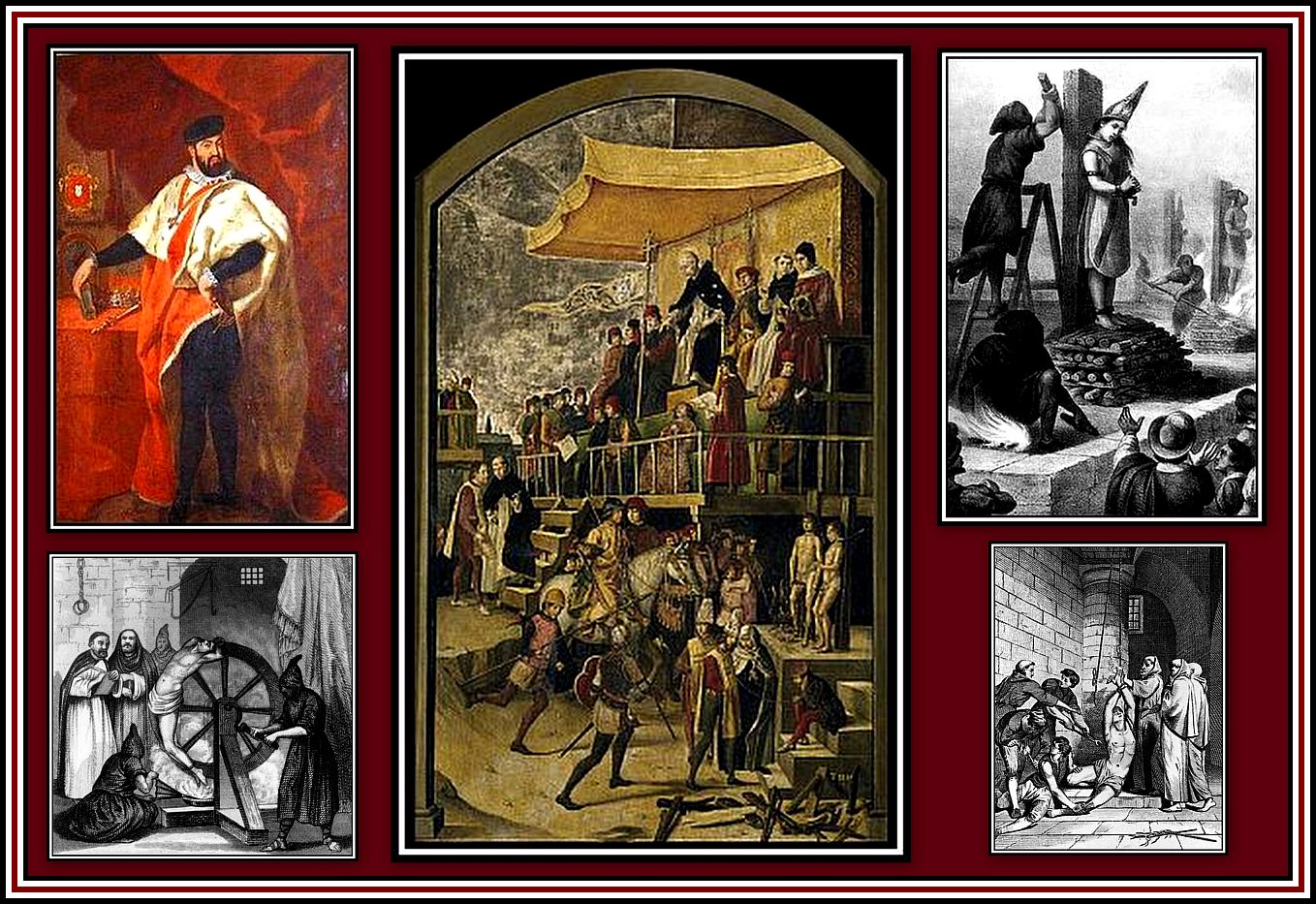

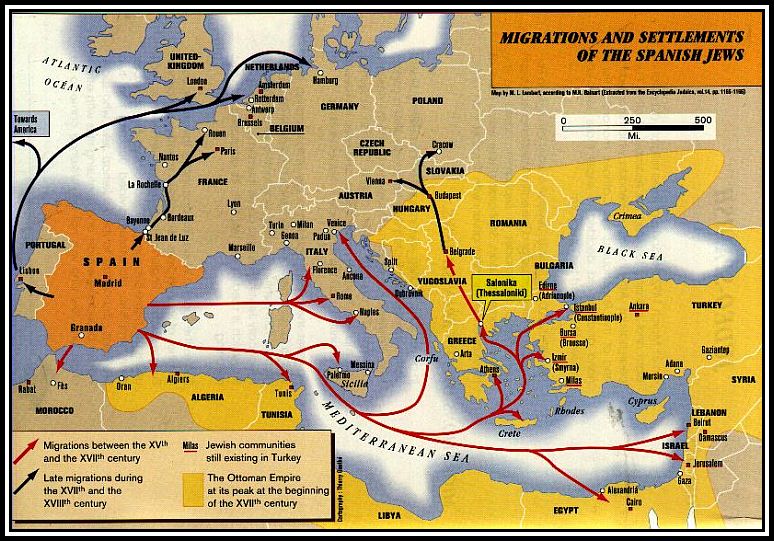

Joseph Salvador was descended from Portuguese Sephardic Jews who had escaped persecution during the Portuguese Inquisition (Inquisição Portuguesa).

Jews have historically used Hebrew Patronymic names. In the Jewish Patronymic system the first name is followed by either ben- or bat- (son of and daughter of, respectively; Bar-, son of, in Aramaic, is also seen), and then the father’s name. Permanent family surnames exist today but only gained popularity among Sephardic Jews in Iberia and elsewhere as early as the 10th or 11th century and did not spread widely to the Ashkenazic Jews of Germany or Eastern Europe until the 18th and 19th century, where adoption of German surnames was imposed in exchange for Jewish Emancipation.

Although Ashkenazi Jews now use European or modern-Hebrew surnames for everyday life, the Hebrew Patronymic form is still used in Jewish religious and cultural life. It is used in synagogue and in documents in Jewish law, such as the Ketubah (marriage contract).

The Inquisition came to Portugal in 1536 and finally ended in 1821, but not before having spread to all Portuguese colonies. To escape this horror, the Salvador Family moved to The Netherlands where they entered into commerce with great success.

The Inquistion

The Inquistion

Top Left: King Joan III who requested The Inquisition in Portugal

Middle: St. Dominic presiding over an Auto-da-fé in Spain in 1475 by Pedro_Berruguete

Top Right: graving of the execution of Mariana de Carabajal by burning in Mexico

Bottom Left & Right: engravings of methods of torture

An Auto-da-fé was the ritual of public penance of condemned heretics and apostates that took place when the

Portuguese Inquisition had decided their punishment, followed by execution of the sentence by the civil authorities.

Auto da fé in Portuguese means act of faith.

The most extreme punishment imposed was execution by burning.

As the execution was more spectacular than the penance,

the term Auto-da-fé came to mean the punishment rather than the penance.

While the Salvadors were in The Netherlands, Oliver Cromwell had assumed power in Britain following the victory of the Roundheads over the Cavaliers in the English Civil Wars of the 1640s. Once in power as Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland, the republican Cromwell readmitted Jews to Britain for the first time since their expulsion in 1290. Cromwell invited back to England the Sephardim presently settled in Amsterdam. He believed that this group would help enrich his country through trade, which they did. In addition, Cromwell was a Puritan and believed that a Jewish presence would hasten the return of the Messiah.

The English Civil Wars

The English Civil Wars

Top Left: Triple Portrait of Charles I by van Dyck; Top Middle: Oliver Cromwell; Top Right: A Puritan Couple

Bottom Left: The Laughing Cavalier by Franz Hals; Bottom Middle: a Roundhead soldier;

Bottom Right: Portrait of John Owen (a theologian) by John Greenhill

As a result of Cromwell’s efforts, the Salvador Family moved to England after living in Amsterdam for several generations. The family brought with them a considerable sum of money, which was used to invest in commence. Francis Jacob Salvador (died 1736), Joseph’s father, soon became a successful merchant in the City of London.

Unfortunately, I have been unable to find a picture of Joseph Salvador.

Unfortunately, I have been unable to find a picture of Joseph Salvador.

This is a picture of his father, Francis Jacob Salvador, painted by Catherine da Costa in 1720.

Joseph Salvador, also known as Joseph Jeshurun Rodrigues, was born in 1716 and followed his father into the City and became a prominent businessman and financier and was a partner in the firm of Francis & Joseph Salvador.

Following the death of Sampson Gideon, an English Jew and Government adviser, the Salvadors helped negotiate loans for the British government. The magnitude of Joseph Salvador’s operations in the world of finance and commerce was such that he was elected to the directorate of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie), being the first Jew to be so honoured.

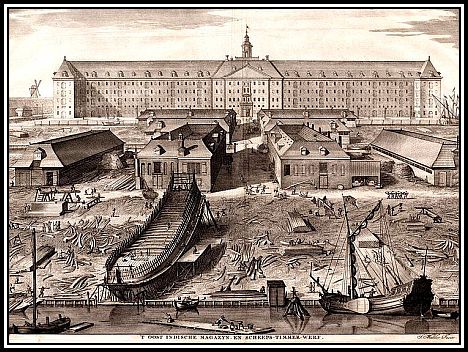

The Dutch East India Company Headquarters, Amsterdam, ca 1750

The Dutch East India Company Headquarters, Amsterdam, ca 1750

As a merchant of prominence with his business headquarters on Lime Street in the City close to where the Lloyd’s Building now exists, Joseph Salvador lived with his wife and children in a grand house that he had built in White Hart Court, just off Bishop Street. In addition, as befitting his position, he built a country home on the old De Graveney estate, now known as the Salvador Estate, in Tooting. He was evidently held in high standing by society for, in addition to his business ventures and his religious undertakings, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1759 and when George III ascended the throne in 1766, he headed the seven-man delegation that congratulated the king on behalf of the Jewish community.

The Royal Society

The Royal Society

Left: 6-9 Carlton House Terrace, home of the Society; Middle: coat of arms;

Right: John Evelyn who helped found the Society

The Salvador Family attended the Portuguese Sephardi Jewish Synagogue (Hebrew: בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת בוויס-מַרקס, AKA Kahal Sahar Asamaim or Sha’ar ha-Shamayim) on Bevis Marks in Aldgate and was a leader in the affairs of this community.

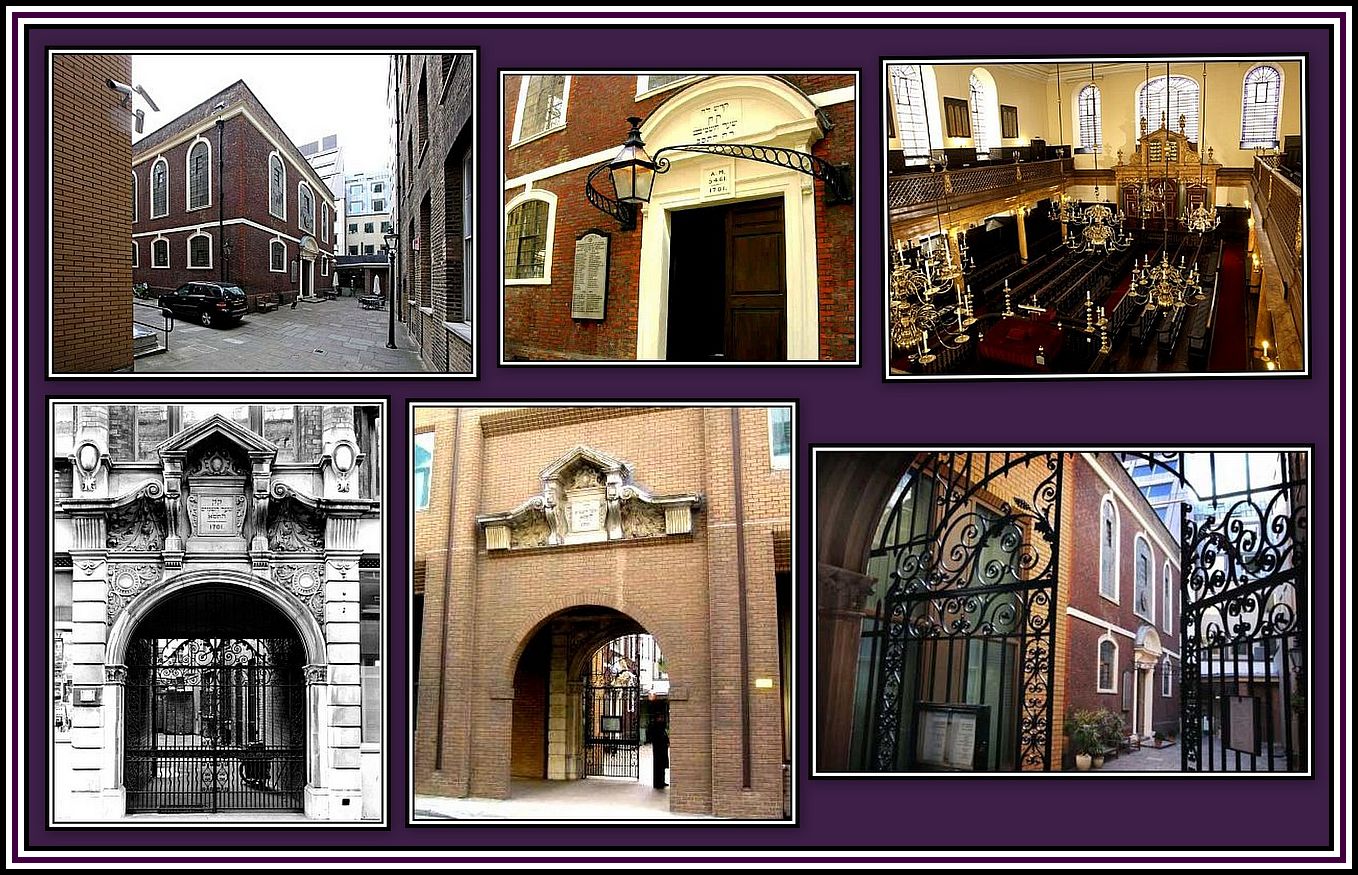

Kahal Sahar Asamaim or Sha’ar ha-Shamayim, Bevis Marks

Kahal Sahar Asamaim or Sha’ar ha-Shamayim, Bevis Marks

Joseph Salvador was a supporter of the Jewish Naturalisation Act of 1753 (Jew Bill) and advocated its passing by Parliament. The Bill allowed Jewish people that were born outside of England to become naturalized British subjects by application to Parliament and came about as a result of their support of the government during the Jacobite rising of 1745. The Jewish financier, Sampson Gideon, had helped strengthen the stock market during this time and a number of young Jewish men had volunteered and joined the soldiers ready to defend the City of London if necessary. Henry Pelham introduced the Bill, which passed The House of Lords with little opposition, but received less support when it was brought before The House of Commons. The Tories believed the Bill represented an abandonment of Christianity, and refused to support it. The Whigs persisted in their support and managed to introduce one part of their general policy of religious toleration, and the bill was passed and received the royal assent.

In some parts of the world, this can involve being attacked, which can take a variety of forms:

for example, being hit with a sandal, being choked, having a thumb pushed in the eye,

being threatened with a chair and having one’s wig or mustache pulled off!

This makes the same process in the British Parliament seem rather tame …..

This makes the same process in the British Parliament seem rather tame …..

following the Civil War, that is.

-oOo-

Joseph Salvador was a patron of those less fortunate than himself and together with members of the DaCosta Family had plans to help settle poor Jewish families in America. In 1733, he funded the passage of 42 people to Savannah in Georgia. The Georgia trustees subsequently voted to ban Jewish immigration, however the founder of the colony, James Oglethorpe, intervened on behalf of the Jews, and the trustees voted to allow the immigrants to stay. Sadly, in 1740, Spain attacked the colony of Georgia causing many of these immigrants to flee out of fear that the Inquisition would soon follow. They resettled in Charleston, South Carolina where the Salvador and DaCosta Families had purchased 200,000 acres of land in the distinct of Ninety-Six, known as Jews Land, in Charleston. Soon after the English Jews settled in Charleston, Jews began to arrive from Germany, The Netherlands and the West Indies.

Leaving for and arriving in America

Leaving for and arriving in America

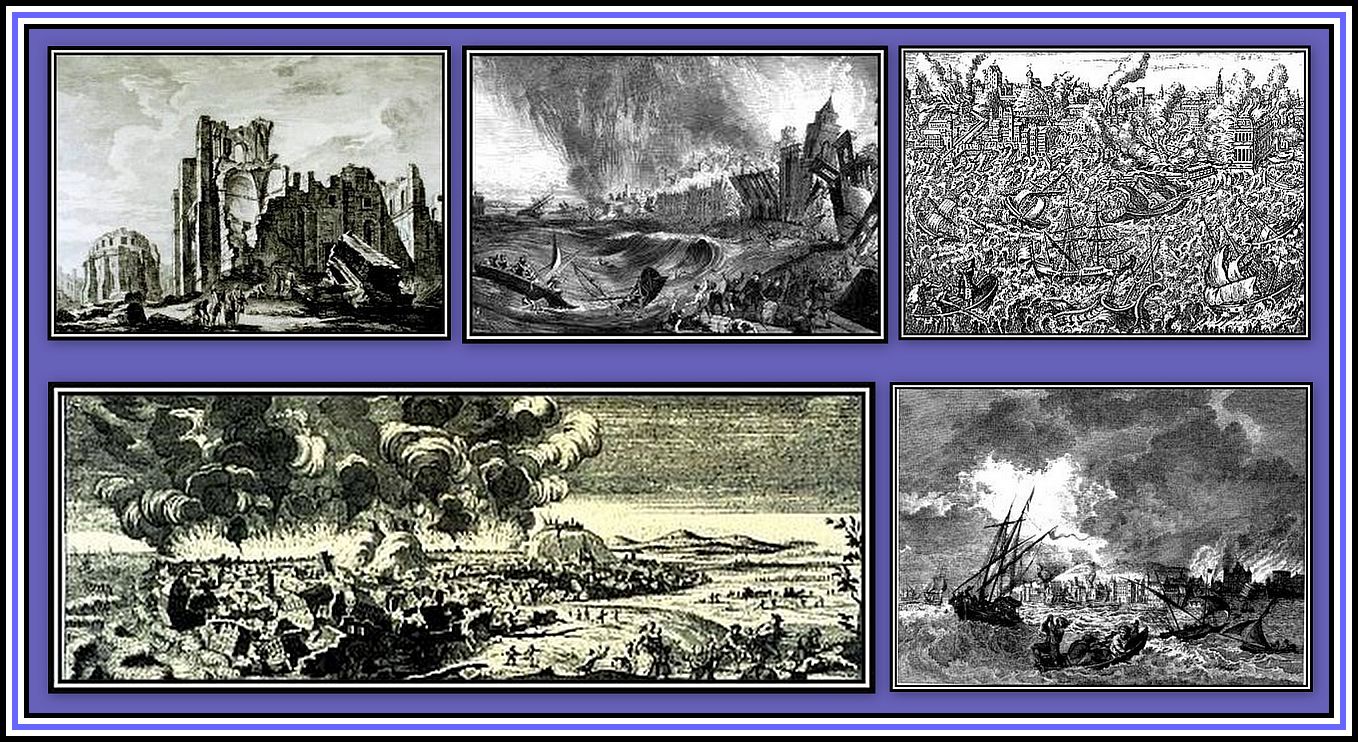

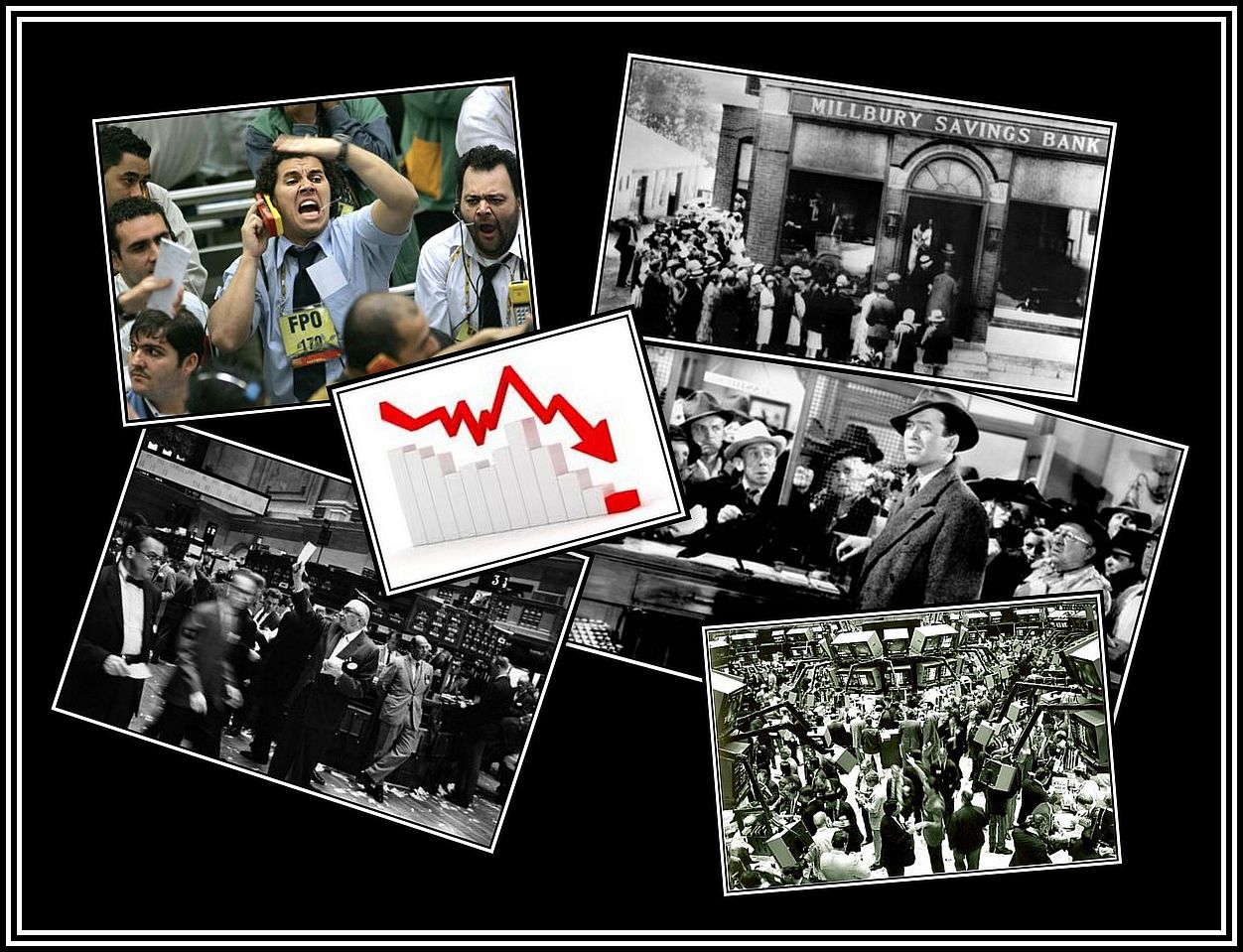

Unfortunately, Joseph Salvador fell on hard times and his fortune declined. His Company had owned much property in Lisbon, which was lost during the earthquake that struck the city in 1755.

Engravings of the Lisbon Earthquake

Engravings of the Lisbon Earthquake

In addition, Joseph was involved in the Dutch East India Company, which had been established in 1602 and had for, almost two hundred years, paid an annual dividend of 18%. Despite this, by the late 18th Century, the company became weighed down by corruption and eventually went bankrupt and was formally dissolved in 1800. Many wealthy Portuguese Jews in England, including Joseph Salvador, suffered great personal losses as a result of the misfortunes of the Company.

In addition to his financial misfortunes, Joseph Salvador experienced other difficulties brought about by his nephew (and son-in-law) Francis from his involvement in the American Revolution. Francis Salvador had gone to Charleston in October 1773 in the hope of rekindling his family’s fortunes. He had left behind his wife, Sarah, who was Joseph Salvador’s daughter, and their three children and planned to send for them once he was settled and the family affairs were in a better state. Once in South Carolina, he became very much involved in the coming revolution and sided with the patriots.

Joseph Salvador sold Salvador House, and presumably the estate, in 1783 following his misfortunes. The house now became a School for Young Gentlemen and was now known as Eldon House. The house was once again sold between 1827 and 1844 and was eventually demolished in 1900. The estate apparently remained and became an isolated village consisting of a cottages and gardens and a Public House and gradually became surrounded by the encroaching urbanisation that was taking place in Tooting. Eventually in 1930, what remained of the estate, which seemed to be a few cottages built in the 19th Century, were purchased and demolished and replaced by the Granada Theatre on Mitcham Road. According to the Tooting History Group, fragments of the old walls of Salvador House are still standing either alongside or incorporated into industrial buildings and backyards together with traces of foundations in car parks. The Group has determined that the exact location of the House was close to the rear of the Granada Theatre and that the Salvador Passage (or alley way) could possibly have been the grand entrance to the former estate.

A Personal View of how the Village of Salvador once looked (!)

A Personal View of how the Village of Salvador once looked (!)

With his fortune very much depleted, Joseph Salvador emigrated to South Carolina in 1784 at the age of sixty-eight and lived in Ninety Six for a while and then moved to Charleston. Apparently what land that remained him, was mortgaged at this time. He lived a simple life in primitive conditions. This is indeed a rather sad and unfortunate end to such a person of standing and one who had been quick to help others less fortunate. Joseph Salvador died on the 29th December, 1786 and is buried in the old Da Costa Burial Ground at Hanover Street in Charleston. I have learned that this cemetery was lost, as the family or the Synagogue were unable to pay the taxes on it. I have it on good authority that there are plans to find the cemetery, or at least what is now is now on the property. Let us wish them well with this endeavour.

When it seems that everything is lost ………

When it seems that everything is lost ………

——oooOOOooo——

All that remains of Joseph Salvador today in Tooting is the little passageway that bears his adopted family name.

——oooOOOooo——

FRANCIS, NEPHEW & SON-IN-LAW OF JOSEPH SALVADOR

Although not strictly part of the Village of Salvador story, the events surrounding the life of Joseph Salvador’s nephew, Francis, bears telling since, although he died young, he nonetheless had led an eventful life and deserves to be remembered.

It often seems that a life is planned and mapped out and all the person has to do is follow it. However, things can happen and events can take the person along a very different path.

Joseph Salvador’s daughter Sarah had married her first cousin, Francis (born 1747) and moved to a home in Twickenham. Francis Salvador had been well-educated and had traveled extensively before joining his father-in-law in the family business. With the downturn of the family fortune, in 1773 Francis went to Charleston where he hoped to establish himself as a planter on a seven thousand acre tract he had acquired from his uncle in the district of Ninety Six. He hoped soon to be able to build a suitable home and so send for his wife and children.

However, events may present themselves and cause a traveler to tread a different path.

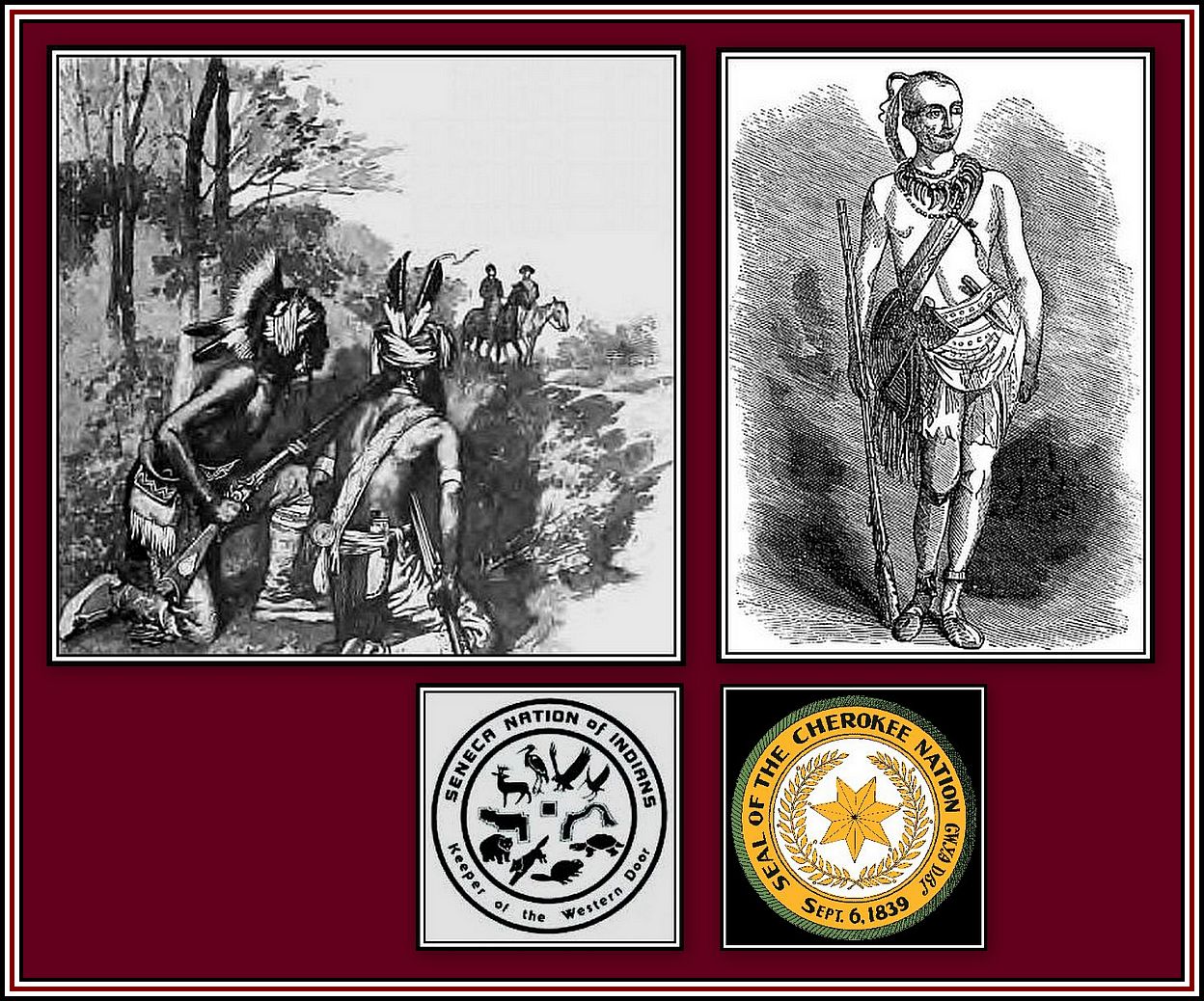

Soon after his arrival in Charleston, Francis Salvador found himself drawn to the growing movement against British rule that had taken root in the thirteen American Colonies and quickly became embroiled in their cause. Within a year of his arrival, and at the age of 27, he was elected to the General Assembly of South Carolina. Although Jews were not legally permitted to vote or to hold office in the American Colonies, Francis Salvador became the first Jew to hold such a high elective office in the Colonies and continued to hold it until his death. The Congress assembled in Charleston in January 1775 and produced A Bill of Rights stating the colonists’ grievances against The Crown and which was brought before the Royal Governour of South Carolina. Salvador played an important role in The Congress, which appointed him to a commission to negotiate with Tories living in the northern and western parts of the South Carolina to secure their promise not to actively aid the Royal Government.

When the Second Provincial Congress assembled in November 1775, Francis Salvador urged fellow members to instruct the South Carolina delegation in Philadelphia to vote for American independence. In addition he played a leading role in the Provincial Congress, chairing its Ways and Means Committee and serving on the committee authorised to issue Bills of Credit to pay the militia.

Salvador was also part of a special commission established to preserve the peace in the interior of South Carolina, where the Crown’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs was negotiating treaties with the Cherokee Indians and to encourage them to attack the colonists. When the Indians attacked settlements along the frontier on 1st July, 1776, they massacred and scalped a number of inhabitants. Salvador mounted his horse and galloped nearly thirty miles to give the alarm. This act resulted in him often being referred to as the Southern Paul Revere. After raising the alarm, he returned to join the militia defending the settlements now under siege.

While leading a small force of 330 men close to his home during the early hours of 1st August, 1776, Francis Salvador and the troop came under attack from the Tories and Seneca Indians on the Keowee River. It was during this ambush that Francis Salvador was shot.

He fell into some bushes, where he was subsequently discovered by the Indians and scalped. He was apparently left for dead, but did not die until forty-five minutes later. Major Andrew Williamson, the militia commander reported that he found Francis after beating back the Indian attack. When he found him, his major concern was whether they had beaten the enemy. When he was told that they had, he said that he was glad. The two men then shook hands and Francis bade me farewell and died a few minutes later. He was buried where he fell.

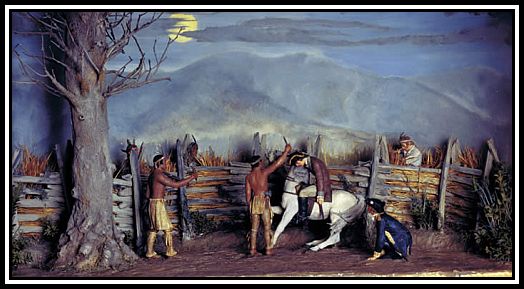

Diorama depicting The Death of Francis Salvador

Diorama depicting The Death of Francis Salvador

The Diorama was made by Robert Whitehead and was on loan to

B’nai Brith Klutznick, in Washington D.C. before coming to

the Museum of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim,

Charleston, South Carolina where it may be seen today.

Mural depicting Francis Salvador on horseback

Mural depicting Francis Salvador on horseback

The mural is present in the Social Hall of

the Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, Charleston, South Carolina

Reproduced with permission of Ms Randi Serrins, docent at the Synagogue

Francis Salvador was the first Jew to die in the American War of Independence and was only 29 years of age at his death. Apparently he never saw his wife and children after leaving England and never learned that the delegation of South Carolina to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia helped the members to adopt the Declaration of Independence.

Those that knew Francis Salvador wrote and also offered verbal testaments to his character, bravery and fervour. In his short life, he showed himself to be a true American Patriot with great concern for the rights of the people living in the American Colonies.

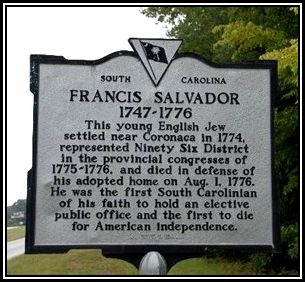

Francis Salvador has been mostly forgotten by most of the populace when the Heroes of the American Revolution are recalled. However there is not the case in South Carolina. Here there is a Commemorative Marker set in Washington Park (City Hall Park), Charleston to remember his deeds. Apparently it is difficult to find, as it is set among other memorials of both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars.

Commemorative Marker, Francis Salvador

Commemorative Marker, Francis Salvador

Born an aristocrat, he became a democrat;

An Englishman, he cast his lot with the Americans;

True to his ancient faith, he gave his life;

For new hopes of human liberty and understanding.

In addition, there is a Memorial Plaque in Greenwood, South Carolina to Francis Salvador, which was placed there by the Jewish Citizens of Greenwood.

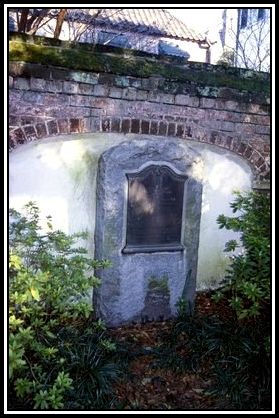

Memorial Plaque, Greenwood, South Carolina

Memorial Plaque, Greenwood, South Carolina

Finally there is a Francis Salvador Award that is presented by the Reform Synagogue, Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, Charleston, South Carolina. The Synagogue was founded in 1749 with a Sephardic Orthodox congregation. In 1841, the Synagogue was firmly committed to the path of religious Reform Judaism. The Sanctuary is the second oldest Synagogue building in the U.S. and the oldest in continuous use.

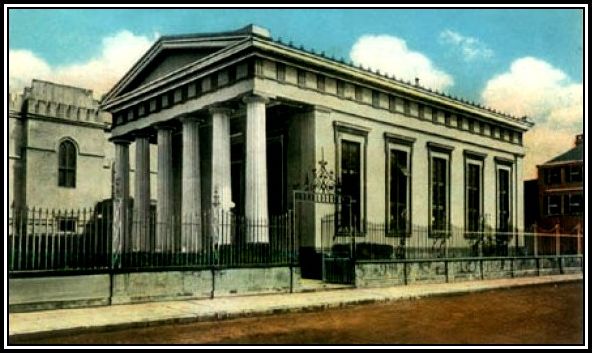

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, Charleston, South Carolina, built in 1841

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, Charleston, South Carolina, built in 1841

The Award is presented at a gala celebration and is a way for the Synagogue to honour by bestowing it to a prominent citizen (or citizens) of Charleston in recognition of demonstrated vision and leadership.

——oooOOOooo——

I am happy to see that Francis Salvador is not entirely forgotten by society. However, poor Joseph has not been as fortunate and the family must content itself with its name on a small passageway in Tooting.

As the French say: En l’absence de grives nous mangeront merles! Which means, sadly, that beggars can’t be choosers.

Photograph reproduced with permission of Ms Diane Barnett

Photograph reproduced with permission of Ms Diane Barnett

——oooOOOooo——

BIBLIOGRAPHY

In addition to the references cited in the text, the following sources were aslo used in the preparation of this piece:

Jewish Encyclopedia: Salvador, Joseph (known as Joseph Jeshurun Rodrigues)

Jewish Encyclopedia: Salvador, Francis

A History of The Jews in England by Cecil Roth

The Jews of South Carolina by Barnett A. Elzas, Associate of Jews College, London, Hollier Scholar, University College, London, Rabbi of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, Charleston, South Carolina,

Merton Historical Society, Bulletin No. 174, June 2010.

The Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain

The Jewish Historical Society of England

I would also like to draw the reader’s attention to Tooting Life.com, which is your guide to everything Tooting can be found including information about the Tooting History Group.

——oooOOOooo——

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to Ms Carmel Donnelly and to Ms Rosemary Hoffman of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain.

Special thanks are also due to Ms Randi Serrins who is a docent at the Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim and at the Historic Coming Street Cemetry, Charleston, South Carolina, U.S.A. I am grateful to these people for their time, help and consideration in the preparation of this piece.

Finally, many thanks are also due to Ms Gillian McGrandles, Senior Library Assistant, Wandsworth Heritage Service at Battersea Library for her time, help and consideration.

Thanks are due to: Ms Abi Stacey and Ms Elizabeth Selby of The Jewish Museum, London; and to Ms Diane Barnett, Mr. David Roe and Mr. Rod Moulding of The Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain.

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to go to THE BATTLE OVER THE FUTURE OF THE BUILDING

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to return to PART NINE: THE GRANADA THEATRE TOOTING

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to go to PART TEN: STARTING A CIRCUIT

——oooOOOooo——

Cick here to return to PART EIGHT: THE PHOENIX THEATRE LONDON

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to return to THE GRANADA THEATRE CIRCUIT

Home Page

——oooOOOooo——

Click here to return to the TABLE OF CONTENTS

——oooOOOooo——

Thanks Charles – A very interesting read.

I have been researching my ancestry and found my great grandfather, Robinson Lewis Salvador, was born in India, near Calcutta in 1834 or 1836?

After that, I have not discovered anything further. We had always thought we hailed from Spain.

I figured that much of India’s history was linked with the British East India Company and found the Salvador family.

I have no proof that there is a linkage, but I feel it in my bones.

Joseph had no surviving sons except for Joseph Lewis Salvador De Moriencourt, his illegitimate son with the Baroness De Moriencourt.

This Joseph was apparently left money by Joseph Salvaddor and most likely bought a commission in the Royal Navy.

He was a Lieutenant with a ship called the Neptune and was active in various English batlles. He died in Boulogne in 1854.

I wish there was some way I could find Robinson Lewis Salvador’s history because I feel strongly that there is a connection there.

Robinson joined the Royal Navy as a merchant seaman and possibly ‘jumped ship’ in Australia about 1857 or 1858.

He married in Warnambool, Victoria, Australia in 1858 and had a tribe of children including twins Joseph Patrick Salvador and Agnes Salvador.

Joesph Salvador married twice and my grandfather, William Ernest Alphonso Salvador was born. Agnes Salvador married Francis Cassidy: my grandmother, Ruby Myrtle Josephine Cassidy was born and later married her cousin- William Salvador. One of their children was William James Salvador – my father.

Thank you VERY much for writing and adding information about your branch of the Salvador family. I wish you the best of luck in your quest. Might I suggest that you contact some of the sources that I mention in the Bibliography shown above. With kind regards. Charles

Hello

My name is kevin Ryan I have started to research my wife Margarets -grand mother

Millicent ernestine Salvadore who married Vivian Edward Evans in Calcutta 1895

her father was J Salvadore.

not much more info yet but I do not think there were too many Salvador s in Calcutta.

Maybe your Robinson Lewis Salvadore is related.