|

| |

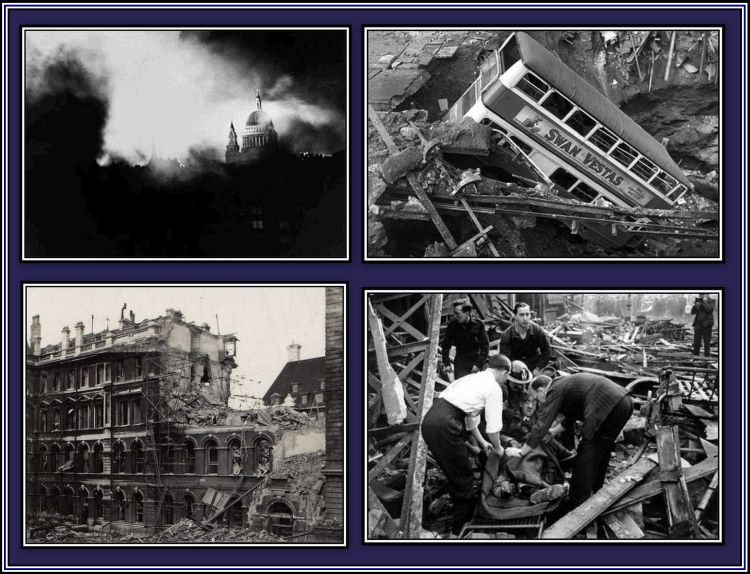

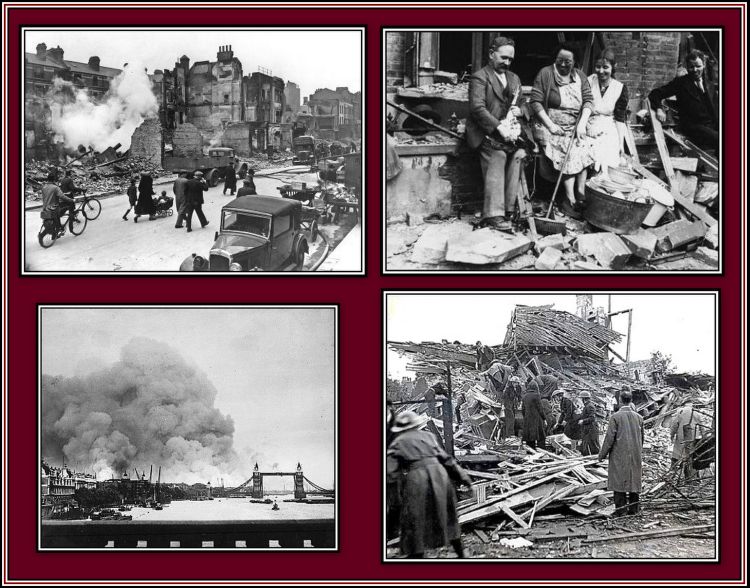

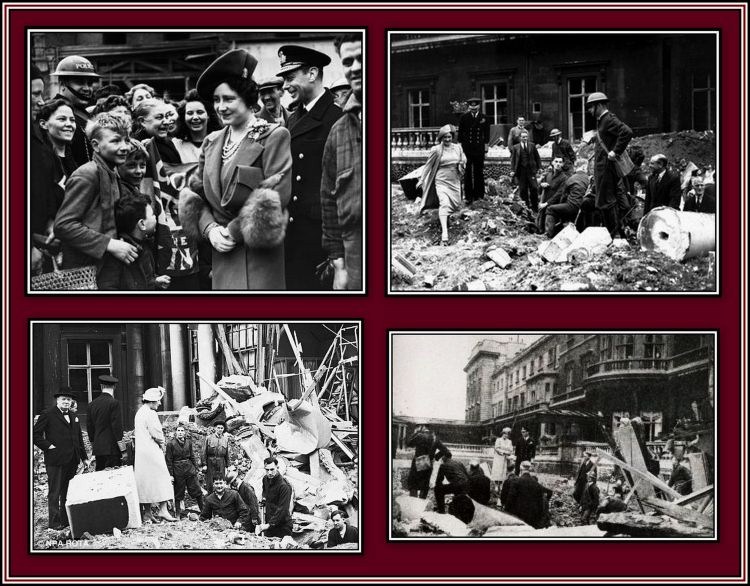

During the 1970s, I was lucky enough to live in Paris. Without doubt the city is spectacular with magnificent architecture and remarkable history. The Parisians are proud of their city and many chose to tell me how much more beautiful it was compared to London. I thought about their comments and soon realized that what they said was true. During a visit back to London, I found myself wandering around the East End and noting all the new and often ugly buildings that had appeared since World War II. As I looked at the new buildings that seemed to be everywhere in the City of London and in the East End, I became aware why Paris was more beautiful. London and the East End in particular, suffered tremendous destruction during the war. Like so many other cities in Europe, massive amounts of explosives were dropped on London that led to the destruction of whole neighbourhoods and many monuments, as well as the loss of life. The Nazis believed that if they bombed London, the people of the city and of the country would be so devastated that they would surrender. As much as Londoners may have loved the city, they valued their freedom far more and chose the destruction of the city over surrender. It is said that Hitler was shocked at the resilience of the average Londoner. Even the King and Queen had their palace bombed and although much was lost, they were proud to share kinship with the average East Ender where so many lost their homes, their loved ones and even their lives. Yes Paris may be more beautiful and some areas may look much as it did several hundred years ago and people may flock to see it, but the price that was paid to maintain this beauty was great. The average Parisian was happy to allow few bombs to drop on their city. Naturally when I began to tell the Parisians this, they scampered away in shame. |

| |

|

Click on the collage to hear Sous le Ciel de Paris |

| |

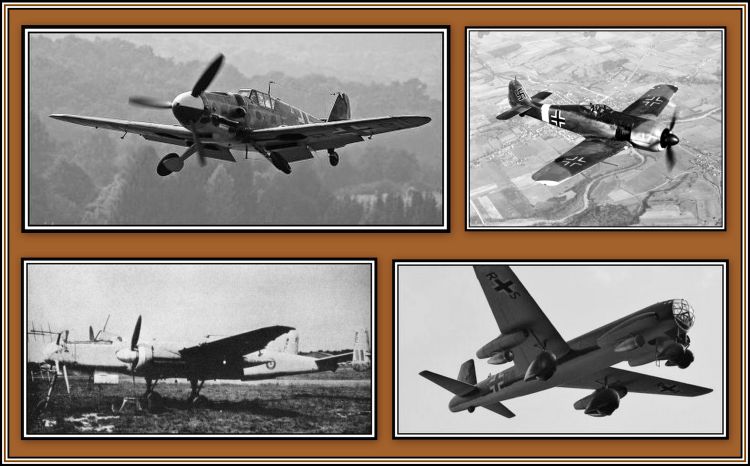

During World War II, London was still one of Britain’s major ports and harboured merchant ships from all over the world in its many docks. Raw materials and goods were unloaded and then sent to various warehouses and places of business both in the city and the country. As a result of its close proximity to the Docks, the East End became a target for the Luftwaffe. |

| |

|

Aeroplanes used by the Luftwaffe |

| |

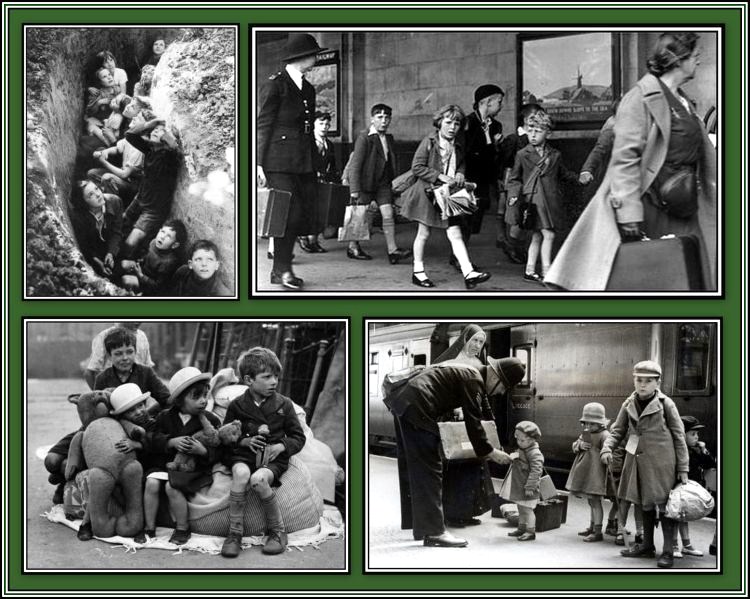

Once the threat of war became imminent, a policy of evacuation of children and civilians involved in non-essential activities was introduced in an attempt to save them from future bombings. According to records, some 1.4 million people were evacuated, however a number returned to London preferring to face whatever Hitler had to throw at them. Londoners were resilient despite the heavy bombing that they had to endure although the numbers increased again in 1943 once the V-1 attacks began. |

| |

|

Click on the collage to hear a wartime tune |

| |

I was born in 1943 and so whenever there was an air raid at night, which was often, my Mother had to get grab me and the things I would need and make her way to the air raid shelter. The enemy preferred to bomb at night when there was no moon and especially when the level of the River Thames was low. Once the Nazis developed the V-1 and V-2 bombs, which required no pilot, bombing occurred at any hour of the day. These bombs, commonly called doodle bugs, were especially demoralizing to the people of the East End. They could be heard overhead as they headed towards their target. Then quite suddenly, their sound would disappear, signalling that the bomb was heading to its point of contact. Apparently, people waited, as if frozen to the spot, as they listened for impact to be made. Sadly, there was nothing to inform them where it would land. |

| |

|

Top Row: The First V1 Fell on Grove Road, London E3

Bottom Row: left, V1; right, V2 |

| |

The Blitz, where Britain was subjected to sustain heavy bombing by the Luftwaffe, lasted from seven months, between September, 1940 and 10 May, 1941. During this time, London was bombed on seventy-six consecutive nights. This caused the destruction and damage of at least one million homes and the deaths of over 20,000 people in the city alone. Another 20,000 were killed elsewhere in Britain during this time. |

| |

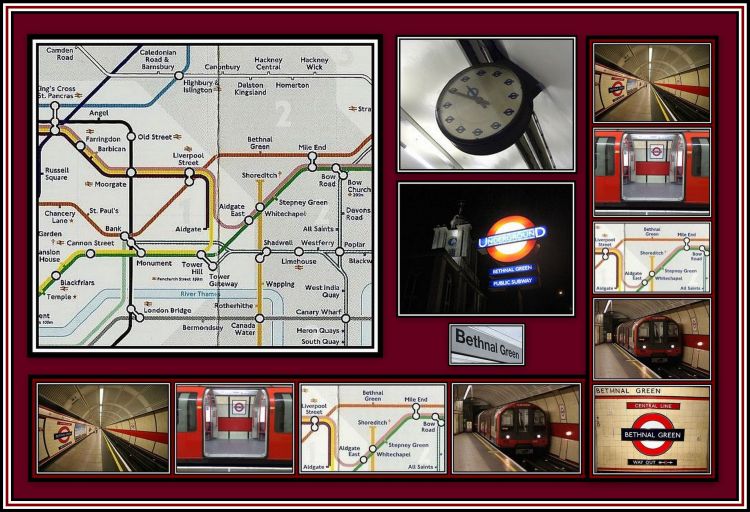

As terrible as all wartime bombings and disasters are, one smaller disaster occurred just before I was born in the area of London where I come from. I was born in Bethnal Green, which is in the heart of the East End. I am a real cockney, being born within the sound of Bow Bells. It was here that possibly the worst wartime disaster in Britain occurred. Although induced by an air raid in 1943, it was not the result of direct hits by German bombs, but the result an unfortunate series of events and miscalculations. |

| |

|

|

Bombing of the East End & Docklands

Click on either collage to hear a wartime tune |

| |

|

| |

When war first broke out, my Mother lived close to the Bethnal Green Underground Station. The station was not officially open at an underground station during the war, but served as a huge air raid shelter with its tunnels being used as underground factories. My Mother would go there on occasion when there was an air raid if she was not on fire-watching duty. My Mother said that the station was popular as a shelter at the start of the war, but soon people preferred to go to smaller shelters close to their homes. By 1943, it tended to be filled only when retaliatory bombing by the Luftwaffe took place, which occurred whenever the R.A.F. bombed German sites particularly heavily. |

| |

|

| Click on the collage to hear a wartime tune |

| |

The R.A.F. had bombed Berlin on the first of March, 1943 and as a result, Londoners expected heavy bombing in reply. On the evening of 3 March, the Air Raid Civil Defence siren was sounded at 8.17 p.m. As usual, people began to make their way to the various shelters and many went to the station. There is a short flight of steps from the outside down to the booking office area, which normally can be manipulated with ease. At 8.27 p.m., an anti-aircraft battery, about half-a-mile away in Victoria Park sent off a salvo of a new type of anti-aircraft rocket. Since this weapon was new, the sound of the explosion was unfamiliar to the people making their way down the steps into the shelter. Apparently, they believed that a bomb had exploded close by, which led to some 300 people being packed into the small stairwell with many more outside trying to enter the station. As the crowd pushed forward, someone tripped on the steps, which were of wood at the time, causing others to stumble. Once help arrived and order was restored, 172 people were found dead at the scene. One of the injured died later in hospital. Of the dead, 62 were children. |

| |

|

Site of the Bethnal Green Underground Station Disaster |

| |

|

| |

This disastrous event was reported in the press and on the radio, however due to the need for wartime censorship, its location was kept secret. A Parliamentary Inquiry was set up to investigate its cause(s). At its conclusion, the Home Secretary made only a brief statement to Parliament. Naturally, the government was accused of hushing up the disaster. Bethnal Green Borough Council was taken to court by two of the victims’ families and sued for damages. The public demanded to know the truth of the cause of the disaster and eventually succeeded in forcing the Home Secretary to publish the report. The conclusion of the inquiry was that poor lighting, the lack of a crash barrier and a lack of supervision by the police and air raid wardens contributed to the events however the principal cause leading to the death of the 173 people was given as the irrational behaviour of the crowd. The report also concluded that there would have been loss of life even if precautions were in place. The Home Secretary had suppressed the report as he believed that its findings would not be believed. |

| |

|

Air Raid Wardens |

| |

The loss of life at Bethnal Green was the largest loss of civilian life in Britain during the war. The largest number of civilians killed by a single bomb was 68 in South London. Naturally, many more people were killed during single bombing raids. I have read that anti-aircraft batteries were not supposed to be installed in a heavily populated area. The housing of such defensive guns in Victoria Park was clearly in violation of this statute. Had the people of Bethnal Green been familiar with the sound of the new guns, perhaps the disaster of 1943 might not have occurred. |

| |

|

Bethnal Green Underground Station Today |

| |

It was not until 1993 that a small commemorative plaque was erected at the site of the disaster. Each year on a Sunday in March, a service in remembrance of those who died is held at the church of St. John on Bethnal Green, which is adjacent to the station. In 2007, the Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust was established with the specific aim of creating a permanent memorial to the victims. Permission has been granted for a memorial, which will take the form of a bronze staircase with 173 points of light that is designed by local architects. In 2010, Barbara Windsor attended the remembrance service and has given her support to the campaign to collect the necessary monies for the construction of the memorial. |

| |

|

Entrance to the Underground Station today

Click on the collage to hear a wartime tune |

| |

|

| |

|

The Proposed Stairway to Heaven Memorial to Those who died in the

Bethnal Green Underground Disaster of 1943 |

Thank you for your article, The Bethnal Green Underground Station Disaster, and for putting it on the website and linking the site to ours. The only thing I wanted to point out was that the Bethnal Green tube disaster was not caused by panic. It was sheer weight of numbers as they would say nowadays. Those going into the station were not panicking until they found themselves completely stuck in the crush.

My mother (a survivor) confirmed that nobody was panicking until they realised they could not get out of the crush as they were all intermingled in a solid mass from floor to ceiling. The delay in releasing them (so it could be kept secret) probably caused more deaths than anything. My mother was trapped for the full three hours. Sadly both my grandmother and a cousin died in the disaster.

Also, I have a copy of the police report written that night by the sergeant in charge, who kept the copy at home as he thought the official version might be ‘doctored'. He maintains that it was a catalogue of things – no central handrail, wet, slippery steps, no policeman or warden on duty at the entrance (nobody knows why), three buses disgorging their passengers at the entrance at once and of course the unfamiliar, deafening sound of the brand new anti-aircraft rocket battery being test fired for the first time nearby that nobody knew about.

Thank you also for urging your readers to donate to the Trust so that a memorial to those that lost their lives may be constructed. That is very welcome as we plan start building on 1st March, 2012. At present, we do not have sufficient funds for the stairway part. Because of the ages of our survivors we feel we must make a start in the hopes that people will come on board with donations or sponsorship once they see something happening.

The memorial was designed by Harry Paticas of Arboreal Architecture, a local small firm of architects in Bethnal Green. He noticed the small plaque over the stairway at the underground station one day, although having used the entrance numerous times without previously noticing it. He researched the event and discovered it was the worst civilian disaster of the 2nd World War and felt it deserved much more than a small plaque that could hardly be read. He got in touch with a survivor and a public meeting of relatives and survivors was called and the design was chosen unanimously. It took over a year to obtain planning permission and in the three years since then we have been trying to raise sufficient funds to build it.

Some people have asked why the Memorial has to be so big. Apart from the fact that it needs to accommodate 173 names and lots of information it also has to meet current health and safety requirements. It also has many significant connections to the disaster itself. By way of an explanation I would like to offer this information.

Firstly, it needed to be of a height so as to impede those wishing to climb it and so avoid accidents. In addition, the final design also needed to accommodate the necessary requirements for those with physical and other difficulties. The chosen design not only had to incorporate the 173 names of the dead, but also be large enough for the public, including those partially sighted, to read the names and individual stories and explanation of what happened that night. Finally the area around the memorial has to be wheelchair-friendly. This requires the area surrounding it to be free from obstacles and to allowed easy access to wheelchair users.

The chosen memorial design will allow the visitor to stand under the stairway area and look up into a hollow space, which will be of the same size as that where 300 people were trapped for three hours waiting to be freed. There will also be 173 conical holes allowing the light to shine through representing those that died.

The Trust also had its own requirements incorporated into the design. After much discussion, it was decided to honour the dead by the use of their full names: for example, instead of Seabrook, B., the memorial will read Seabrook, Barry 2 years 9 months. War Memorials do not normally represent the full names of the fallen in this manner since they are honouring military personnel. The Trust also decided upon having a small memorial garden area with a bench and wheelchair area where those wishing to sit and contemplate and pray may do so in a more calm and peaceful atmosphere. The bench will have both a back and arms to support the needs of the elderly. The paving stones used are to be laid out so as to be perfectly in line with the stairs going down to the station where they perished. Finally, there is to be a 25-watt light bulb. This is a remembrance of the only light in the station on the night of the disaster. In the placing of such requirements, the Architect and the Trust hope these symbols will represent the events and atmosphere of that night.There are a number of other concerns and considerations that the Architect and Trust had to take into account such as ways to impede vandalism and the use of the area by skateboarders. In addition, the Memorial has to be environmentally friendly and ensure that the rainwater from the roof will be collected and recycled (a European Union requirement).

Finally, there are to be several small plaques to be placed along the plinth of the Memorial, which will tell individual stories by survivors and relatives of those who died. Each will be poignant and powerful and will be part of a jigsaw puzzle telling the story of what happened. The Bishopsgate Institute, in conjunction with the Trust, is in the process of making audio recordings by various survivors and of relatives’ memories for posterity. From these it is hoped to produce an audio unit-for-hire to be made available to visitors as they view the Memorial.

The Trust believes that the chosen design of the Memorial incorporates the various needs and requirements outlined here. The Memorial will be at the corner of a busy crossroads and the Trust believes that it will stand out and be readily noticeable by passersby and represent fully the magnitude of such a dreadful disaster.

Once again thank you very much for your interest and help. It is always good to make acquaintance with a fellow Bethnal Greener.

Honorary Secretary/Trustee of the charity Stairway to Heaven |

| |

The Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust’s website is: http://www.stairwaytoheavenmemorial.org/ and donations may be made here. No donation is too small – every little helps and brings the Trust just that bit closer to building the memorial. |

Both my parents came from Bethnal Green. My brother, Ernie, and sister, Betty, were both born at 141 Valance Road and attended William Davis School in the borough. I was born at St. Peter’s Hospital, which no longer exists. I attended Haige Street School, which is situated at the Stepney of Valance Road.

I remember when an unexploded bomb or landmine landed on the Valance Road viaduct railway line. Our street and others were requested to evacuate our shelters and homes and move further afield whilst the brave disposal men disarmed it.

In late 1940, after the docks and warehouses were bombed, my dad moved us to a lovely quiet part of Palmers Green in north London. My grandmother continued to live at 141 until the houses were pulled down. She was very upset when her home was demolished as she enjoyed living in the neighbourhood and would take in washing and ironing for some of her neighbours that had careers. She loved the social interaction that existed in her community and missed it very much once she was re-housed to a ground floor flat. One point of interest is that we believe that she did the washing and ironing of the mother of the infamous Kray brothers, who lived close by.

My mother told me that her cousin Carrie (unfortunately I don't know her surname) died in the Bethnal Green Tube Disaster. Apparently she had been pushed against the wall, but managed to hold her baby above her head, allowing the baby to survive the crush. Sadly, Carrie did not. Carrie's husband had erected an Anderson shelter in their back yard in 1939, but on that day, Carrie chose to go to the underground station to seek safety.

My uncle Rupert and aunt Vera owned a Greengrocers shop along Victoria Park Road. Their house, at 28 Wetheral Road, E9, was hit by a V2 rocket on 7th December, 1944 killing both of them together with their two daughters, Eileen and Jean.

Life is full of irony, as my father Jack, who had been so considerate in moving us out of the East End during the war to the relative safety of north London, should survive the war years only to die in a road accident 1960.

Irene |